We have written before about the different ‘shapes’ of recovery that the Scottish economy could face in the months ahead.

Earlier this month, we had official confirmation that Scotland entered recession in the first six months of the year – with an eye-watering fall of 21.7% between Q4 2019 and the end of Q2 2020.

So that’s the “\” shape of the recession sorted.

But what next?

Hope of a sharp bounce back – a ‘v-shaped’ recovery – have all but disappeared. The fear is that the recovery will be long leading to a ‘U’ or ‘bathtub’ shaped recovery.

But there is increasing evidence to suggest that an alternative ‘shaped’ recovery is on the horizon – a ‘k’ shaped recovery.

The basic idea behind this is that some parts, and some households/individuals in our economy, will recovery relatively quickly; others, will take much longer to get back on their feet. So perhaps not exactly a ‘k’ (perhaps more a smiling crocodile: Ed: enough tenuous shapes please) but something where there is a clear divergence in outcomes.

How likely is this? And in what parts of our economy might it play out in the months to come?

Sectors

The first way in which such a recovery pattern may emerge is through the performance of different sectors.

In a modern economy, all sectors are closely integrated, so in a recession very few sectors, and the businesses that work within them, are immune.

But the scale of the ‘economic shock’ is never shared equally. [NB: Of course, there will be some firms, e.g. PPE manufactures and online retailers, who will have benefited during the crisis, but they are very much in the minority of businesses].

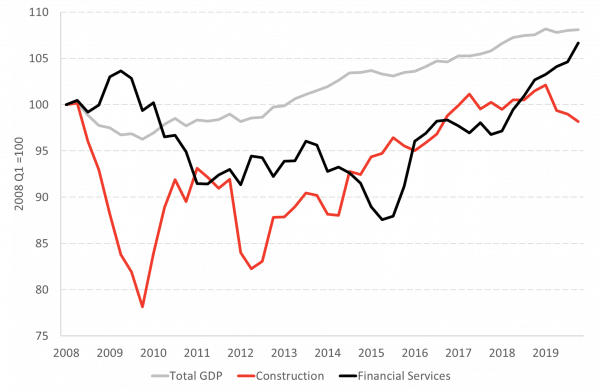

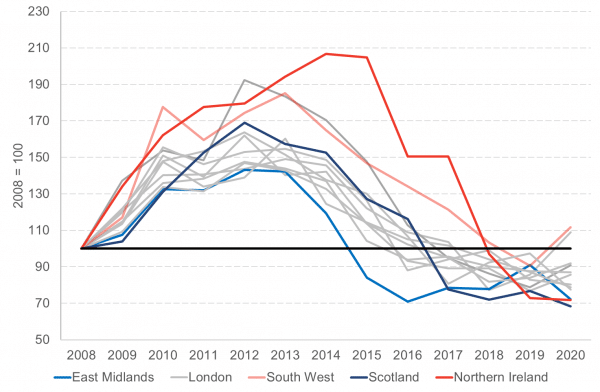

Let’s take the 2008/2009 financial crisis and recession as an illustration.

As the chart highlights, whilst the Scottish economy as a whole had recovered to its pre-recession peak by 2013, it took almost a decade for the two sectors at the epicentre of the crisis – construction & financial services – to make-up the ground that they lost during the crisis.

Chart: Scotland’s economy during the 2008/09 financial crisis – recession and recovery

Source: Scottish Government

What about this time?

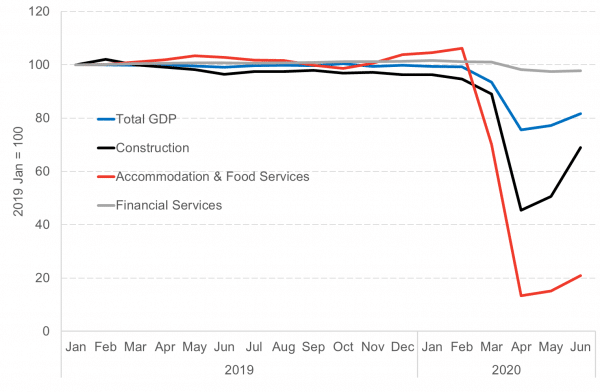

There are reasons to believe that the sector splits in 2020 will be even greater.

For some entire industries, the lockdown restrictions stopped trade completely.

Large parts of our economy – from restaurants, bars, tour operators through to gyms, traditional retail, airports and other services relying upon social spending – effectively ceased trading for months. Even now as restrictions are lifted, many of them operate under significant restrictions. Recovery for businesses in these sectors will be long. Sadly, many jobs will be lost, particularly when the furlough scheme ends in the autumn.

In contrast, in some other parts of the economy, from financial services through to legal and accountancy firms, activity has been able to continue pretty much as normal (albeit with work taking place remotely).

Chart: Sector performance in the Scottish Economy since lockdown

Source: Scottish Government

How long this will last is, of course, uncertain.

But arguably, the predicted variation in economic outcomes for different sectors that we first discussed in our March Commentary has been even greater than we imagined. The longer the restrictions last, the longer it will take the economy to recover at an aggregate level, and it will increase the possibility of a much wider split emerging in relative performance by industry.

Households

Another way in which the recession could lead to a sharp difference between the ‘haves-and-the-have-nots’ is via its impacts upon different households in the income distribution.

Again, and as we have written before, the economic fallout from the lockdown won’t impact upon all households in the same way.

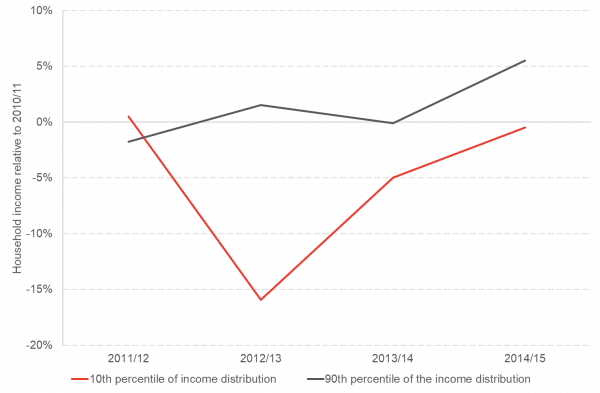

The experience of past recessions suggests that those on the lower end of the income distribution can be most impacted by downturns in the economy.

Once again, take the financial crisis as an example.

It took until 2011/12 for the impact of the financial crisis to feed through to reductions in average real household incomes, first hitting higher incomes then spreading to other parts of the income distribution.

Data on incomes can be volatile and it is better to look at longer term trends rather than one off data points. Overall, the last recession saw incomes fall for both lower and higher income households, with a subsequent recovery which looked different depending on incomes.

Chart: Scotland’s inequality in impact on after housing costs income following the 2008/09 financial crisis

Source: DWP

Again, there are reasons to think that the 2020 recession could have an even greater split than before.

This time, the hit to earnings is likely to happen much sooner than was the case in the last recession due to the impact of the lockdown.

But for some, work has been able to continue from home and salaries have been relatively well protected. These tend to be those in professional services and the like.

But for others, earnings and job security look much less positive.

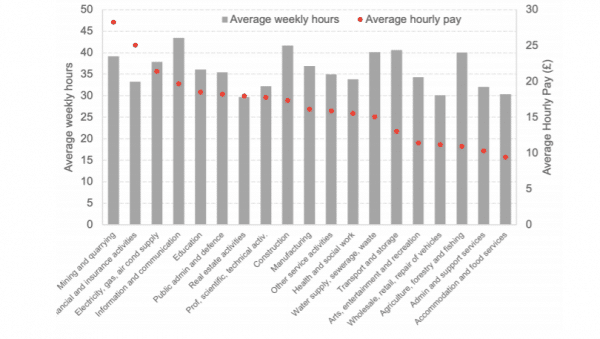

Sadly, the sectors that have been disproportionately hit during the recession, such as hospitality and retail, tend to employ people on lower average wages.

Chart: Earnings by industry, Scotland, Q4 2019

Source: ONS

Of course, many of these sectors are also businesses that employ women, with the potential for this crisis to widen some of the gaps in labour market outcomes – perhaps reversing trends in recent years which saw a narrowing of some gaps.

Age

Another variation in relative impact of the recession could come about is through age.

Although the hospitalisation and mortality rates of young people (aged 16-24) from Covid-19 are relatively low, past evidence suggests that it is young people that tend to suffer negative consequences from recessions. This can lead to ‘scarring’ – i.e. permanent reductions in economic, health and social outcomes for young people who are pushed into unemployment or poverty as a result of a recession.

Our friends at IPPR Scotland published some new analysis last week, looking at the latest projections for youth unemployment at the UK level and translating them into equivalent figures for Scotland. A worst case scenario would see 140,000 young people unemployed later this year, the highest level since records began.

The chart below shows what happened during the last financial crisis. The youth unemployment rate rose sharply in most parts of the UK, increasing by over 50% in many parts.

Chart: Youth unemployment in the UK during past financial crisis

Source: ONS

The chart also shows that there was also a variation in regional performance – both in terms of scale of relative increase in the unemployment rate and the length of time it took to return to pre-crisis levels.

Both the Scottish and UK governments have announced schemes to help tackle the projected rise in youth unemployment. Although it remains to be seen if these measures – and the scale of financial support that they are offering – will be enough.

Region

Finally, and as we have highlighted before, there will be a regional dimension to the recession and recovery too.

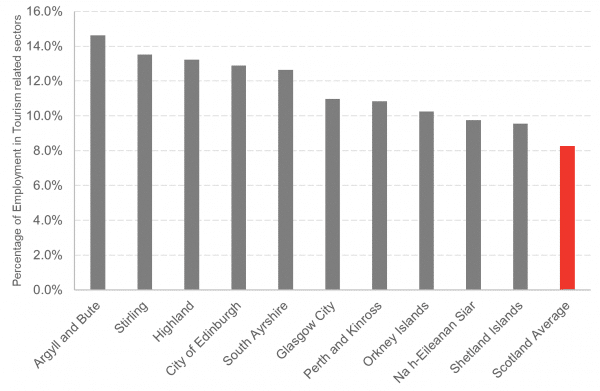

Regions differ from each other economically for a variety of reasons. One obvious way that they differ is in the sectors that are most important for jobs.

Back in March we discussed the exposure of many rural communities in Scotland to a sharp fall in tourist numbers this summer (via small hotels, guest houses and tour operators). Many of these communities face wider structural challenges, whether that be access to services, access to markets or an ageing population.

The chart below shows the % of employment taken up by tourist facing sectors by region.

Chart: Percentage of Employment in Tourism related sectors

Source: Scottish Government

However, there are signs that rural areas have seen a bounce back in some activity in the latter half of the summer as restrictions eased and domestic tourists returned which has not been reflected in our cities. There are other challenges for our cities too, particularly in the light of the substantial shift to homeworking. This week we’ll be discussing these issues on our latest podcast with our good friend Jeremy Peat in the context of Edinburgh.

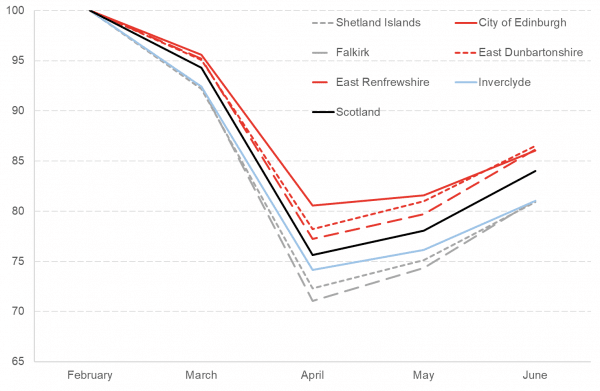

The chart below models some illustrative changes to regional economic performance across Scotland, apportioning the national split of activity by each region’s share of GVA in each sector.

Chart: Modelled variations in regional economic activity: Feb to March 2020: ‘Top’ and ‘Bottom’ performing local authorities based upon sectoral shares

Source: FAI Modelling

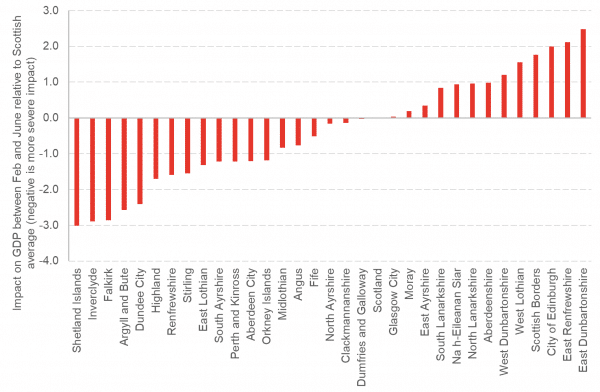

All areas are projected to see sharp declines, but there are important differences – as illustrated in the chart below.

Chart: Modelled estimates on regional economic activity: Feb to March 2020

Source: FAI Modelling

These are modelled estimates, so should be used with caution. But given that they highlight the simple point that regions are structured different from each other on a sectoral basis and some sectors have been impacted more than others, then they provide a useful guide for areas that are more exposed than others.

Of course, there were already significant differences in economic performance and wellbeing between and within areas of Scotland. We also know that some communities have – in the past – much less resilience to economic shocks, whether that be because of differences in the skills of the local labour force, challenges around social deprivation, the productive capacity of its business base, the age profile of its population or issues of connectivity.

There remains much uncertainty about how the economic crisis that we are now in will pan out.

One thing that we can be certain of is that many of the inequalities that existed in our economy prior to the crisis will be exacerbate by the fallout from COVID-19. The journey back to a ‘better normal’ will be that bit more difficult. Much more than warm words and statements of ambition will be needed.

Authors

Mairi is the Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, she was the Deputy Chief Executive of the Scottish Fiscal Commission and the Head of National Accounts at the Scottish Government and has over a decade of experience working in different areas of statistics and analysis.

Emma is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Head of Research at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Graeme Roy

Dean of External Engagement in the College of Social Sciences at Glasgow University and previously director of the Fraser of Allander Institute.