The fear of a sharp rise in unemployment is a real one in this economic crisis.

Last week’s latest Quarterly Economic Indicator from the Scottish Chambers of Commerce provided an insight into the harsh reality for many businesses in Scotland just now. In recent days, we’ve had a number of announcements of planned job losses across the UK.

The situation for young people is particularly challenging. We know that any period of unemployment at a young age can have long-term scarring effects, with implications for economic, health and social outcomes.

In response, the Economic Recovery Group from the Scottish Government recommended a Scottish Jobs Guarantee for 16 to 24-year olds. Such schemes have been used in the past – most notably the Future Jobs Fund announced in 2009 – with the tentative evidence suggesting that it did indeed have a positive impact upon outcomes.

The detail on the proposed Scottish Jobs Guarantee is so far limited, although the government have moved quickly with the appointment of Sandy Begbie, to lead its formation.

It seems unlikely however, that without major government funding, such a scheme could be run at scale.

Any scheme that relies upon brokerage between businesses and job seekers or businesses themselves to lead this drive, whilst having clear merits, is likely to only have an impact at the margin given the wider economic climate.

To be successful, additional public sector funds will be required to share its costs with businesses.

Unless the Scottish Government is able to shift resource from within its budget (which would require a cut in spending elsewhere), and given that it cannot borrow to fund revenue spend even if this is investment in human capital, all eyes will be on the UK Government to implement a scheme. If this was to happen, either Barnett Consequentials would flow to the Scottish Government enabling them to set up their own scheme or, it could be administered by DWP in Scotland (perhaps in partnership with skills and education providers).

We expect new announcements from the UK Government in the coming days about their plans for recovery, which are likely to include some support for youth unemployment. Whether or not they plan to introduce such a jobs guarantee scheme is uncertain. Indeed, it was the Conservative led Coalition who cancelled the Future Jobs Fund shortly after entering office in 2010, arguing that it provided a poor return compared with other less-expensive employment schemes.

Statistics on Youth Labour Market

Since the financial crisis, Scotland’s youth labour market performance has been a key area of success.

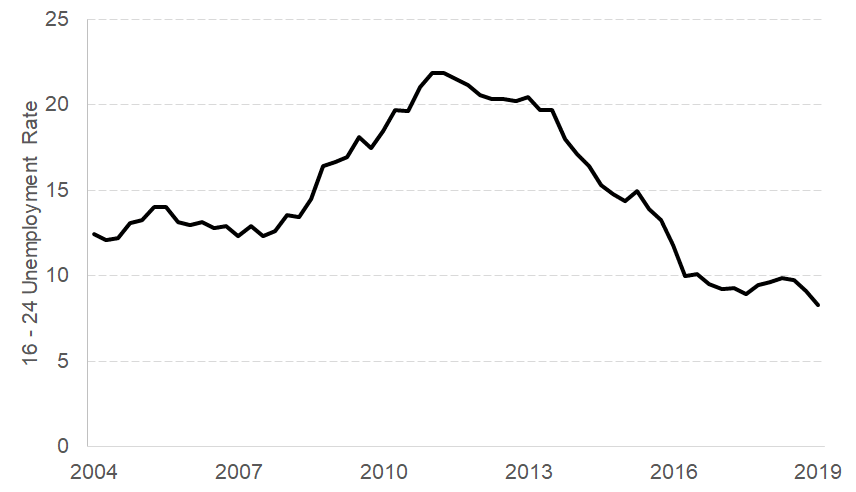

Since peaking at around 23% in 2012, the youth unemployment rate had fallen to a record low level of around 9% in late 2019 (Chart 1).

Chart 1: 16-24 year old unemployment rate %, Scotland

In comparison to other countries in the EU, Scotland had one of the lowest youth unemployment rates in Europe. In the latest available data in 2019, the average youth unemployment rate in the 27 EU countries was around 16%.

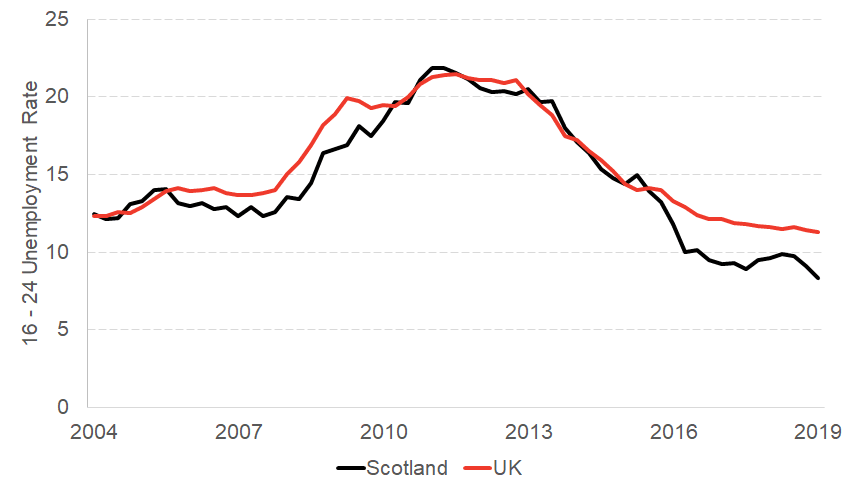

Youth unemployment in Scotland has consistently been below that in the rest of the UK in recent years (Chart 2). Again, at the end of 2019 the youth unemployment rate in Scotland was estimated to be some 2 percentage points lower than in the rest of the UK.

Chart 2: 16-24 year old unemployment rate %, Scotland & UK

But the outlook looks challenging.

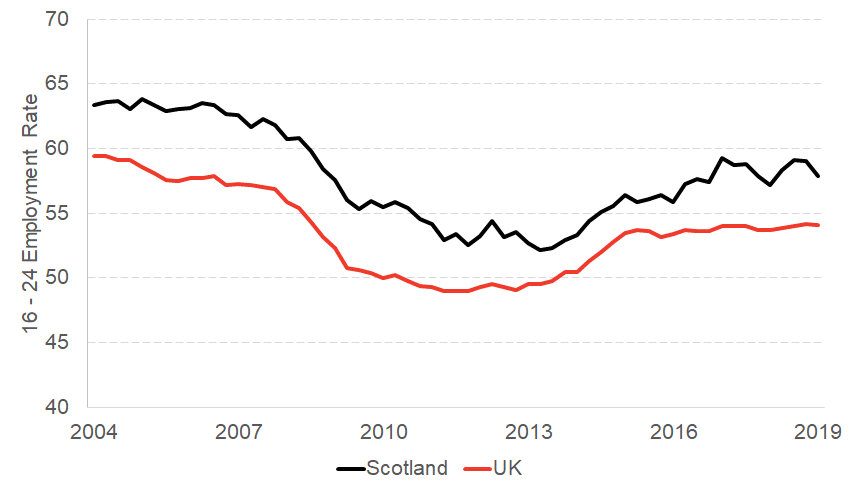

In recent months we have seen some falling back in youth employment levels.

Chart 3: 16-24 year old employment rate %, Scotland & UK

And in the most recent LFS data, covering the period to the end of April 2020, which we suggest using with caution as these are not National Statistics, but which the Scottish Government have used in the past for comparisons, has 16 – 24 unemployment in Scotland at 13.1%, higher than that in England (11.5%). See P17 of the Scottish Government Publication here, and pay particular attention to the notes at the bottom of the table.

Predictions are that – without government action – youth unemployment will rise sharply in the coming months:

- The Resolution Foundation have, for example, forecast a rise in youth unemployment of around 600,000 across the UK. 16-24 year olds unemployed in Scotland in 2019 represented around 6% of the UK total – applying this share to the Resolution Foundation’s forecast would suggest an increase in youth unemployment in Scotland of over 37,000.

- In the aftermath of the financial crisis, youth unemployment peaked in 2011 at 95,000 (or 21.8%) in Scotland and 988,000 (or 21.5%) in the UK around the same time. If this was to be repeated, this would be a rise in Scotland of around 60,000 on current levels.

We also know that young people tend to be concentrated in sectors that are most exposed to the current crisis – see our earlier article here. The average age of workers in the accommodation and food services sector is for example, 4 years younger than the next ‘youngest’ sector.

The IFS have calculated that people under the age of 25 are over 2½ times more likely to be in sectors that have been shut down vis-à-vis older workers

In looking at what the long-term implications of this, there are two separate but inter-related issues. A paper in the new Economic Observatory discusses these issues in detail, with some excellent links for further reading.

- Firstly, there is lots of evidence that points to the scarring effects that youth unemployment can have on society – these don’t just relate to economic outcomes but also to wider health and social outcomes.

- Secondly, for young people entering the job market at this time are likely to find themselves at a personal disadvantage, even if they still go on to achieve success, compared to their counterparts in other more fortunate years. They are – on average – likely to experience lower wages and weaker employment opportunities.

A jobs guarantee

It is clear therefore that support for young people entering the job market at this time is crucial.

A ‘jobs guarantee’ is clearly a major policy intervention, and has attracted support. [As an aside there will also be important roles for education and skills training too – this was the principle behind the Scottish Government’s Opportunities for All initiative back during the last recession. This will not only invest in the skills capacity of young people, but help provide them with support and learning during the economic crisis]. Support for young people in work will clearly help mitigate the worst scarring effects of the crisis, leading to benefits not just now but in the future. It may also help support businesses by providing additional resource at a challenging time.

As we highlighted, key is turning a ‘good idea’ into a practical initiative that can work immediately. It might be irritating to make this point, but it’s crucial to move swiftly and decisively. IPPR Scotland estimate that there are around 50,000 young people leaving education this summer, with thousands more finishing up an apprenticeship.

There are a number of hurdles for policymakers to jump-over. And lessons from the Future Jobs Fund in the UK point to some insights.

The first – and most important – issue will be who funds it?

It seems unlikely that, at least at the current time, schemes that rely upon a brokerage between employers and job seekers won’t have the desired impact at scale. As the latest Chamber of Commerce Survey highlighted, businesses are cutting back on staff significantly – and this is something that is likely to accelerate once the furlough scheme comes to an end. Only with government funding can a scheme support the thousands of young people looking for work.

Second is how much funding? A scheme at scale, and for the length of time the Scottish Government has proposed will require a major investment. For example, £1 billion was set aside for the Future Jobs Fund during the financial crisis by the then UK Government.

The Advisory Group on Recovery’s proposal is that the “scheme should offer secure employment, for a period of at least 2 years, to 16-25 year olds, paid at the Living Wage, with access to training, apprenticeships and the possibility of progression.” The average salary of a full-time worker on the Living Wage would be around £17,000 per annum. As an illustration, a government contribution of £10,000 with 10,000 young people supported would cost £100 million per annum (of course, this can be adjusted for different public fund contributions and levels of young people supported). So how much would a government contribution be? How long for? And at what level of pay?

Unless the Scottish Government is able to shift resource from within its budget (but at the cost of reduced spending elsewhere), all eyes will be on the UK Government to implement a scheme for the UK as a whole – either with Barnett consequentials or through design of a scheme administered by DWP.

Third is speed of delivery. The quick roll-out of any guarantee at scale isn’t straightforward. One of the reasons why the furlough scheme has been successful is the quickness in which HMRC could use existing administrative structures for swift delivery. This would suggest that a mechanism that is straightforward makes sense. Who might be best to implement such a scheme at pace is unclear. Relying upon local government for example, to implement such a scheme has advantages in terms of local knowledge. But capacity to deliver at speed – after years of budget cuts – would be a concern.

Fourth is what conditions are attached? Clearly the government will wish to ensure that its Fair Work objectives are delivered as a minimum. Other conditions, around training and progression are clearly important too. But the more conditions, the more complex a scheme is to run and the less willing some businesses might be to engage – particularly in times of distress.

Any scheme will have to balance the trade-offs between securing jobs now – when businesses are facing huge uncertainty – and ensuring gains aren’t only temporary. Much like recent discussions of the unwinding of the jobs retention scheme have highlighted, support will need to be aimed at ensuring long-term attachment to the labour market and not only keeping young people in jobs for its duration.

Finally, it will be important when designing such a scheme to not see it in isolation. The Future Jobs Fund was designed to ensure that any jobs supported by the scheme were ‘additional’. But, in reality, particularly at a time of businesses shedding jobs, this is hard to monitor. Even the evaluation of the Future Jobs Fund noted that its results were likely to be an overestimate. There is a risk that a well-intentioned scheme to support young people, crowds out opportunities for older workers, many of whom will have caring responsibilities and will be at risk of being pushed into poverty.

Similarly, schemes designed to support employment, can’t be seen in isolation from the urgent need to support businesses now, many of them working on exceptionally small reserves and face a hugely uncertain future. For them, survival is the dominant thought for them at this time.

Support for young people in this crisis must be a top priority to help ensure that this crisis – brought on by a temporary shutdown in our economy – does not lead to longer lasting challenges. Everyone agrees that this is the case. What we need now is an immediate workable plan, with major investment, fast delivery and a mechanism that ensures genuine additionality that is the interests of young people, their fellow employees and business.

Authors

Head of Research at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Graeme Roy

Dean of External Engagement in the College of Social Sciences at Glasgow University and previously director of the Fraser of Allander Institute.