With the pandemic forcing many people to work from home for the first time, much has been said about how home working could influence the future of work and, with it, the future of city centres.

Some claim that it presents an opportunity to work flexibly, to save on commuting times and to boost the UK’s productivity which has been particularly sluggish since the financial crisis of 2007-08.

For others, it could lead to a loss of the innovation that results from informal discussions and presents difficulties in effectively managing staff.

“Whether it is creative sparks being dampened, existing social capital being depleted or new social capital being lost, these are real costs and costs which would be expected to grow, silently but steadily, over time. They weigh on the other side of the ledger when it comes to assessing the case for home-working. They cast doubt on whether it will lead to the promised land of improved productivity and greater happiness.”

Andy Haldane

Chief Economist, Bank of England

But which jobs are likely to be most or least affected by home working? And what are businesses saying about their experience so far?

Homeworking by occupation

Of course, not all jobs can be performed at home.

One potential concern around increased levels of homeworking in the future is a potential divide between the jobs which are more easily done at home – typically professional occupations and management roles – and those which cannot, such as cleaners, waiting staff, machine operatives and the roles of many of the key workers during the pandemic.

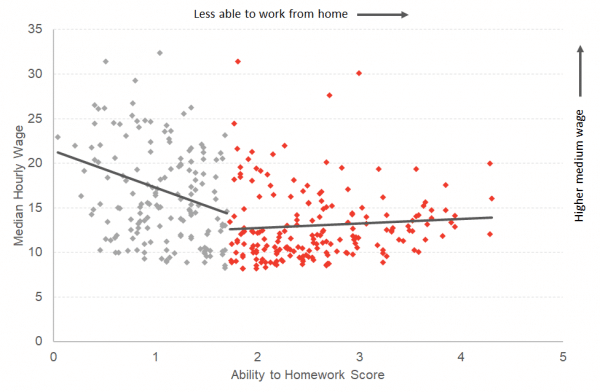

Typically, the jobs that can be more easily done at home are also better paid. Chart 24 compares the median wages of 365 occupation groups in the UK to their scored ability to work from home.

This indicator was built by the ONS, considering five factors that are associated with being less able to work at home – e.g. the more a job has to be carried out in a specific location, the higher the score. So, for each occupation, the higher the score, the less likely it is that is can be carried out from home. The occupations with an above average ability to work from home (so a lower score) are shown in grey while those with a below average ability to work from home (so a higher score) are in red.

Chart 1: Ability to homework score and median wage by occupation classification, UK

Source: ONS; Fraser of Allander Institute

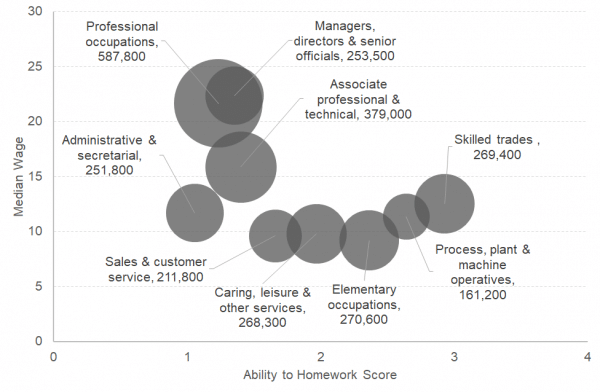

Looking within Scotland, a large amount of employment is supported in lower paid occupations that are less likely to work from home.

Chart 25 shows groups of occupations by their median wage and ability to homework score, with the size of the bubble representing the occupation group’s employment in Scotland.

Three of the four categories here – representing around 46% of Scottish employment – have much higher median wages and more chance of working from home.

Chart 2: Occupation ability to homework Score and median wage, size of the bubble represents employment in Scotland

Source: ONS; Fraser of Allander Institute

This provides some insight into the differential impact on jobs during the pandemic. Those with lower wages are less able to work from home and likely will have been affected to a greater degree than those in higher paid occupations.

But what about the business experience of working from home?

Home working – views from business

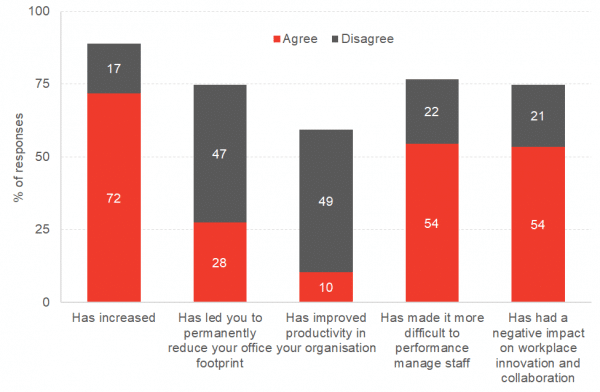

We surveyed over 500 businesses in October to understand their views on the impact of home working.

Around 3 in 4 of the businesses had seen homeworking increase – this is perhaps the least surprising figure.

What was more interesting was that only 10% believed that it had improved productivity in their organisation. The majority also thought it had made performance management of staff more difficult and that it had a negative impact on workplace innovation and collaboration.

To what degree this effect is due to homeworking being suddenly thrust upon these companies it is hard to say. It may be that this picture improves as businesses are able to set up processes for home working.

Other evidence also suggests that saving on the commute results in more hours of work being undertaken. This may go some way to mitigating falls in productivity.

Despite the negative views around productivity, management and innovation, more than one in four businesses says that home working has led them to permanently reduce their office footprint.

More work needs to be done to understand whether this is due to cost savings, due to requests from staff for more flexible working in the future or for other reasons.

What is clear right now is that there is a desire to try new ways of working. Whether these changes are for better or for worse, it is difficult to say. The choice to be able to work flexibly – whether from a workplace or from home – is commonly spoken of as vital to the future of work. But this is a choice that seems primarily available to the most privileged in society.

Chart 3: “Do you agree or disagree that homeworking in your business…”

Source: Fraser of Allander Institute

Authors

James is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. He specialises in economic policy, modelling, trade and climate change. His work includes the production of economic statistics to improve our understanding of the economy, economic modelling and analysis to enhance the use of these statistics for policymaking, data visualisation to communicate results impactfully, and economic policy to understand how data can be used to drive decisions in Government.