The construction industry has been disrupted enormously over the course of the Coronavirus pandemic, not least because that vast majority of the workforce is not able to work from home. Whilst the official UK Government advice is for sites to continue to operate if work can be carried out at safe social-distances, the Scottish Government has advised all non-essential construction work to stop. This has meant site-closures across Scotland and, inevitably, drastically reduced activity in the sector.

We can’t say with any certainty the damage the pandemic will have on the sector. We do know, however, that the effects of any impacts will be widespread – on the latest available data, the construction sector is estimated to account for 5.8% of GDP and roughly 6.6% of employment, or around 177,000 people.

Medium term demand for the sector may also be impacted more severely than other sectors due to the responsiveness of activity to wider economic trends – a bounce back is not guaranteed and indeed employment is still lower than prior to the previous recession over 10 years ago. Construction is an important industry not only for its own sake but also the wider supply chains it supports in Scotland – compared to some other industries these effects are relatively high.

Here, as we did in a previous blog focusing on tourism, we use the latest Quarterly Labour Force and Family Resources surveys to estimate the how those who work in the construction sector differ to those in all other sectors, and discuss how they might be affected by the policies in place to stop the spread of the Coronavirus.

Age and gender

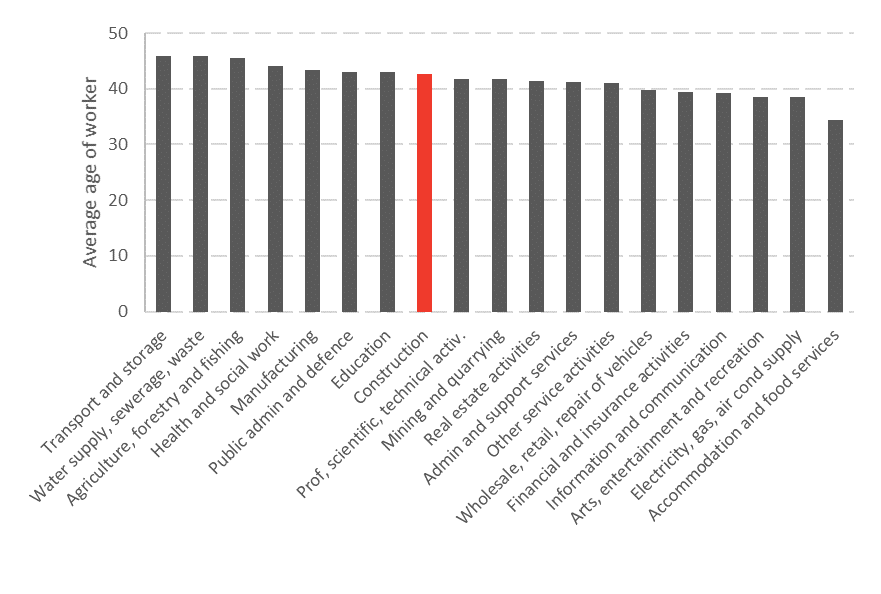

Those that work in construction industry are not particularly young or old relative to other industries. In fact, the average age of its workforce falls almost in the middle of the distribution among industries, and, at roughly 43 years, is about the same as the education and professional and scientific industries (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Average age of worker by sector

Source: Labour Force Survey, Oct-Dec 2019, ONS

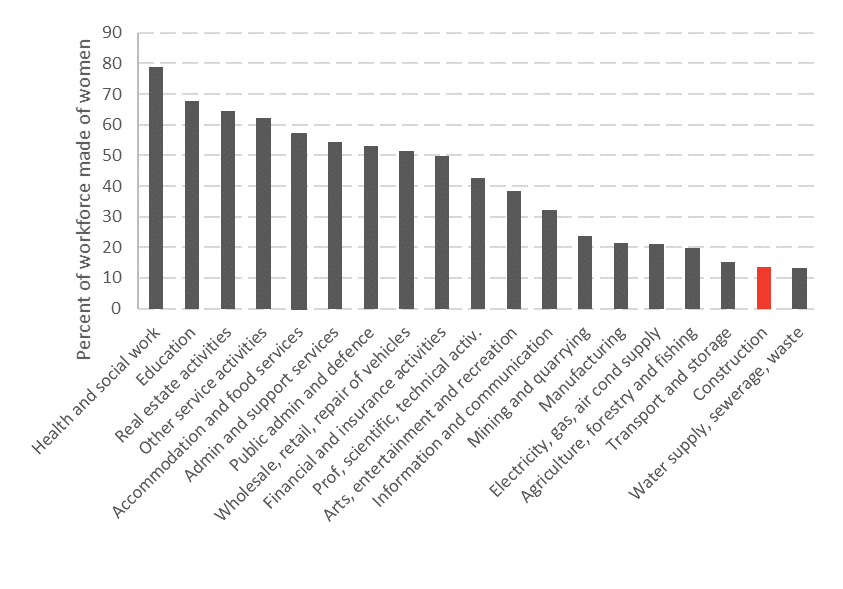

The construction sector is, however, dominated by men. Chart 2 shows that, proportionally, it has the second smallest proportion of women in its workforce, with only around 14% of those in employment within construction being women

Chart 2: Proportion of workforce who are women by sector

Source: Labour Force Survey, Oct-Dec 2019, ONS

Pay

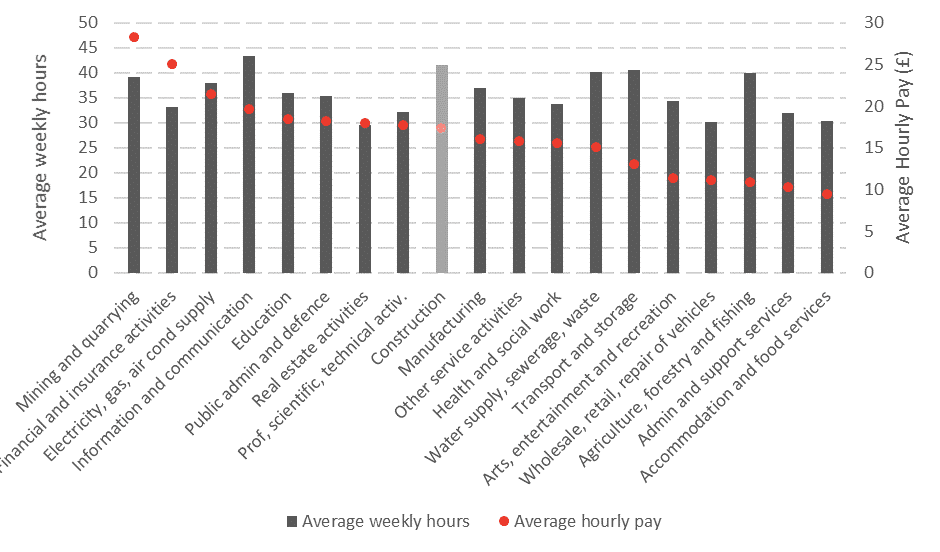

Those in the construction industry work relatively long hours, and their average hourly pay is higher than over half of the other industry sections in Scotland (Chart 3). Although not ‘high’ when comparing across the economy, average hourly pay among construction workers is sizeably larger than among those in the Accommodation and Food Services industry, the lowest paid sector who have been among the most affected by lockdown measures.

Chart 3: Average pay and hours by sector

Source: Labour Force Survey, Oct-Dec 2019, ONS

Self-employment

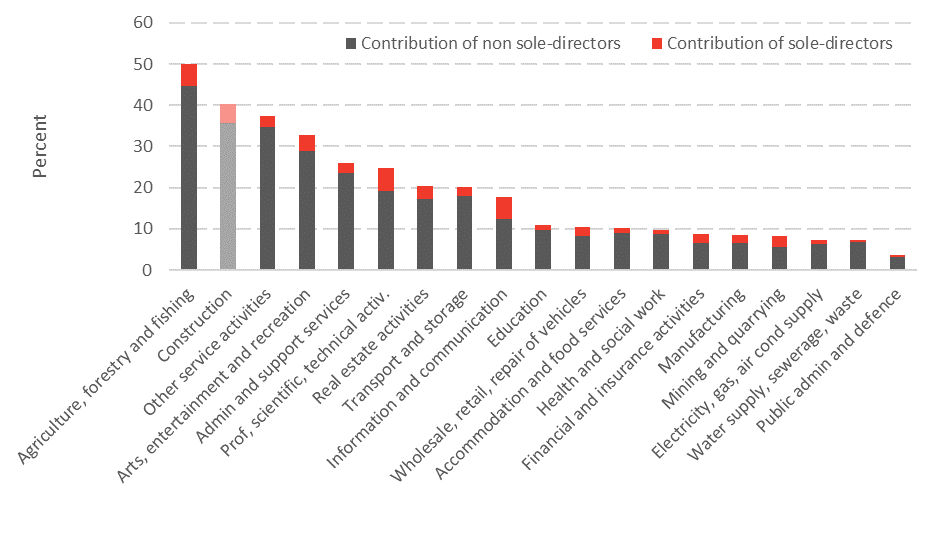

One prominent aspect of the construction industry is self-employment. Those who work in construction related industries are far more likely to be self-employed than the average worker – just over 40% report to be self-employed in the latest data (Chart 4).

Chart 4: Proportion of self employed and whether sole directors by sector

Source: Labour Force Survey, Oct-Dec 2019, ONS

Within the self-employed category lies a number of different working arrangements that surveys, such as the LFS, struggle to identify. Interviews with workers in the sector describe the precarity of employment and lack of employment rights for those not directly employed. These workers are likely to be more at risk during this period of shutdown.

One group that we can identify through the LFS are directors of companies. Just over 10% of those the self-employed in construction industry report to be the sole-director of a limited company. As we heard from the STUC in our podcast yesterday, these arrangements are sometimes made at the bequest of employers.

Household composition

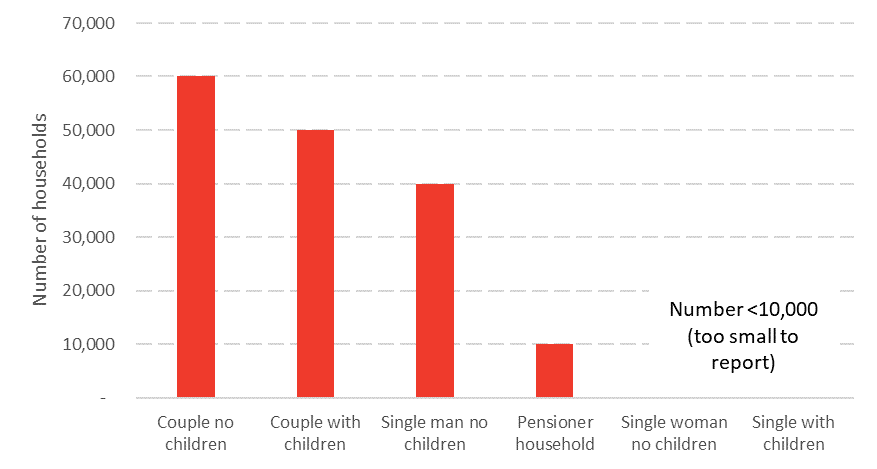

There are approximately 170,000 households with an adult working in the construction sector, of which two thirds are within couples and in the vast majority of cases both adults are working. The majority of the residual are single adult males. In terms of financial resilience, those who are reliant on the income of one adult may be more vulnerable to sudden changes in earnings.

Chart 5: Household composition of workers in the constructions sector

Source: FRS & HBAI, 2015-18, DWP

Household income

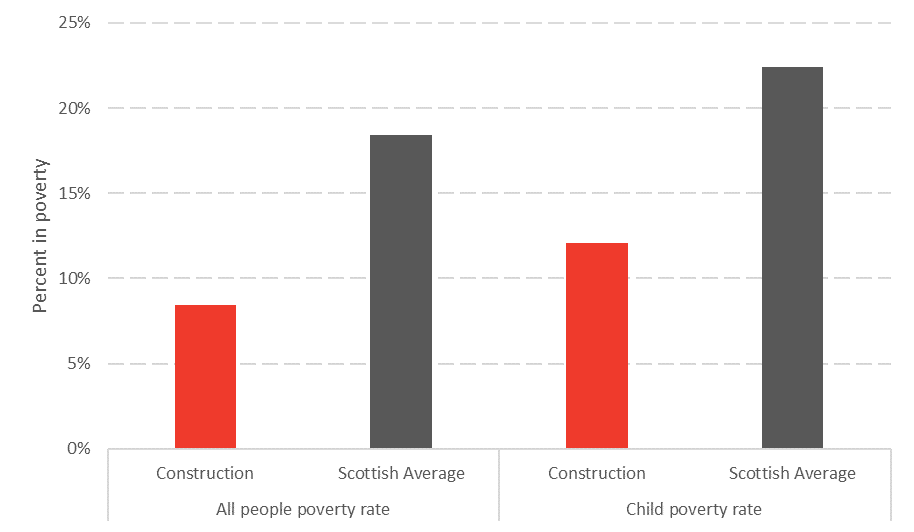

Reflecting the combination of above average wages and long average working hours, household incomes are above average for those employed in the sector, and poverty rates on average are lower.

Chart 6: Poverty rates

Source: FRS & HBAI, 2015-18, DWP

Impacts on workers in the sector

There is support on offer for workers in the sector. Where work has been postponed, employers can use the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) to furlough workers and pay 80% of their wages, but as with any industry, it depends whether or not the employer decides to use it. For the self-employed, there is support through the Self Employment Income Support Scheme which is available to many sub-contractors who work via the Construction Industry Scheme (if they meet the conditions for support), although pay outs from the scheme will not begin until June. Those employed via umbrella companies have now been included in the CJRS following appeals from the industry and unions.

However, there will be workers who fall between the cracks. For example, the LFS statistics show that 10% of those self-employed operate as directors of limited companies. We don’t know from the data the structure of peoples’ income, but we do know that If these are paid mainly through dividends, they would not be covered by the Self Employment Income Support scheme.

Because of the differential guidance in Scotland compared to England, it is likely that more workers will be affected by site shut downs in Scotland. From a health and safety perspective, this may well be the right decision given obvious challenges around social distancing on a busy building site, as well as during travel to and from work. However, this differential advice means that more people in the sector in Scotland will be requiring financial support, and may also require if for longer than their counterparts in England if Scotland continues to impose more restrictive guidance for the sector. For employees laid off rather than furloughed, and for those that don’t qualify for self-employment support, the financial impacts will of course be severe.

Any shutdown of firms, even if short term, will challenge survival of firms. Even if staff costs are reduced due to government support, other overheads still remain, and cash may simply run out. The Federation of Master Builders in Scotland have said that there is evidence that two thirds of small to medium sized businesses only have cash to cover another two or three months if the current circumstances continue.

The relatively high incomes that the sector allows, and the fact that the majority of workers live with another working adult, does suggest that these households may be more resilient to any financial shocks in the short term compared to, for example, the accommodation and food services sector which we looked at last week where low age, relatively low income and high incidence of living alone painted a picture of financial vulnerability. The construction sector does however pose different questions given the high proportion of self employment and the precarious nature of their employment contracts. Longer term there is no doubt that workers will suffer financially if government support is reduced and/or if firms cannot survive until they are permitted to go back to operating as (or close to) normal, and from past experience, we know that it could take a long time for the sector to recover.

The way this sector has been treated in Scotland is one of the few areas where guidance has been different north and south of the border. As discussed, there could be both positive (health) and negative (financial) implications of this. We will continue to monitor this sector to see how this unfolds.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.