Today we published our latest economic commentary – you can read the full commentary here.

In this article, we summarise 10 key bullet points:

1. There is still high uncertainty within the Scottish economy and forecasting its recovery is difficult.

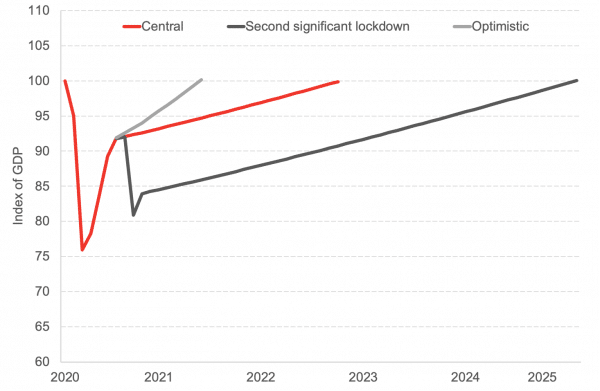

Given the uncertainty in the economy, we have avoided providing any specific point estimates or a central forecast for the next few years. Instead, we highlight different scenarios.

The optimistic scenario sees firms bouncing back relatively quickly over the coming months with a full recovery across all industries by summer 2021. However, given that there is no vaccine as of yet and last week’s announcement of further restrictions, this is increasingly unlikely.

In our central scenario, any hope for a ‘v-shaped’ recovery is all but gone, looking more towards a ‘k-shaped’ recovery. This scenario predicts certain industries to recover quicker than others, with the economy not recovering fully until Autumn 2022.

We also provide a scenario taking a second significant lockdown into consideration. What we see is that if the economy were to go back to similar lockdown restrictions as to what was experienced in March, it would take the economy up to 4 years to recover fully.

Chart 1: Scottish Economic Growth scenarios: 2020 to 2025 based upon return to ‘pre-crisis level’

Source: FAI Calculations

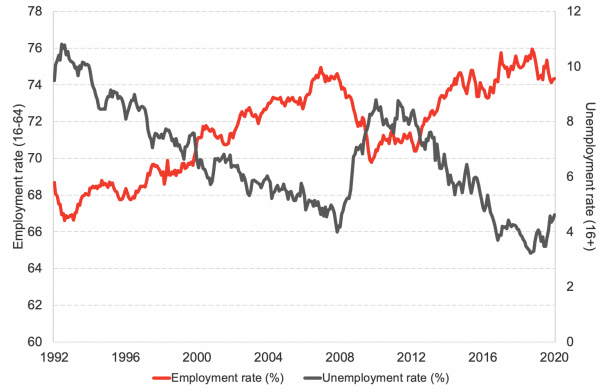

2. The full effects of the pandemic on the labour market remain to be seen as government furlough scheme begins to unwind.

The latest Labour Force Survey for Scotland suggests that the unemployment rate remained around historically low levels (4.6%) while the employment rate remained relatively high (74.3%), with the Scottish labour market slightly weaker than the UK as a whole.

Chart 2: Unemployment and employment rate, Scotland

Source: ONS

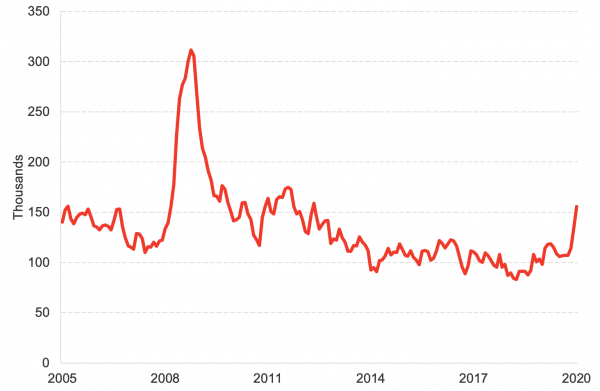

3. The outlook for unemployment remains poor, with redundancies increasing, highlighting the inevitable spike in the unemployment rate.

The winding down of the Government furlough scheme means that we are seeing a rise in the number of people being made redundant, with unemployment looking set to rise over the coming months. Redundancies increased by 48,000 in the three months to July 2020.

Chart 3: UK redundancies

Source: ONS

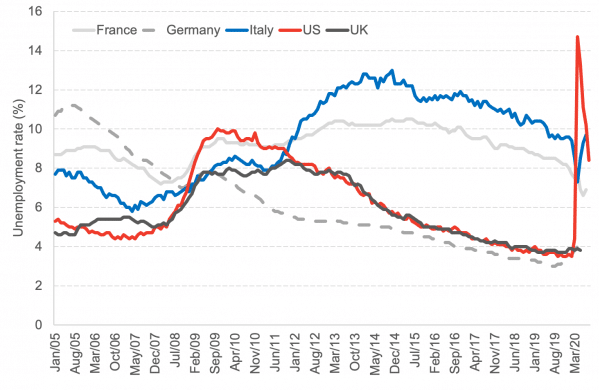

4. Similar to Scotland and the UK, the pandemic poses the greatest risk to global economic recovery.

Many other European countries are facing the same challenges in the labour market, with unemployment rates rising, and projected to continue to rise over the coming months.

Chart 4: Unemployment rate, January 2005 – August 2020

Source: OECD

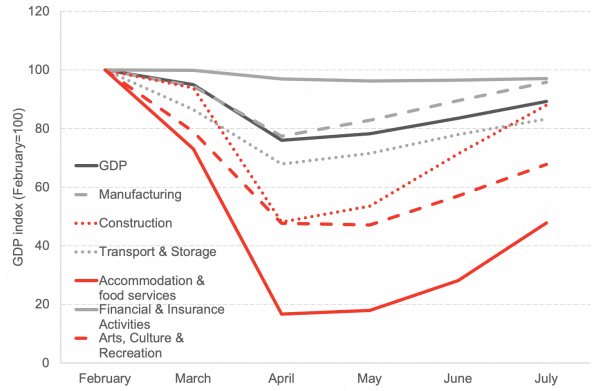

5. This is the most uncertain the immediate outlook for growth has been in recent times, with many sectors producing significantly less than pre-Covid levels.

Latest GDP figures for Scotland highlighted some bounce back in growth at the start of the third quarter in July of 6.8%, however, this is expected as we are recovering from a very low base. The economy is still over 10% smaller than in February.

It is important to focus on the levels of output in each industry and not the growth rates. For example, output in the accommodation and food services industry grew by 70% in July but is producing under half of what it was in February. Whereas the financial industry experienced output growth of 0.5% in July however, it is producing around 97% of what is was in February.

Chart 5: Sector performance in the Scottish economy since lockdown

Source: Scottish Government

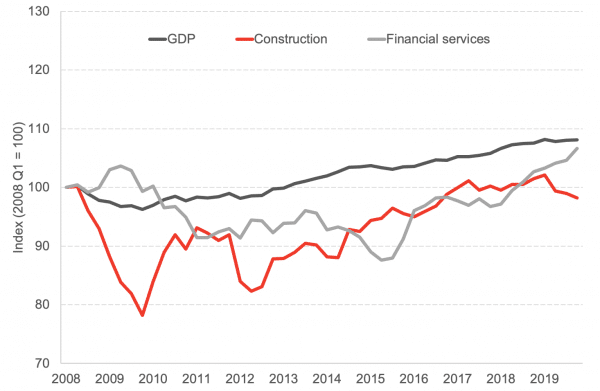

6. When compared to the recession of 2008/09 and subsequent recovery, it could take far longer for multiple sectors to make a full economic recovery during this crisis, leaving long-lasting scarring effects on the economy.

Scotland entered into a recession in the first half of the year – with an eye-watering fall of 21.4% between Q4 2019 and the end of Q2 2020. Chart 1 analysed the forward-looking path for growth and recovery in the economy, but what do historical trends tell us?

In a modern economy, all sectors are closely integrated, so in a recession very few sectors, and the businesses that work within them, are immune. However, the scale of the ‘economic shock’ is never shared equally.

Looking at the financial crisis of 2008/09, the Scottish economy as a whole had recovered to its pre-recession peak by 2013, but it took almost a decade for the two sectors at the epicentre of the crisis – construction & financial services – to make-up the ground that they lost during the crisis.

Chart 6: Scotland’s economy during the 2008/09 crisis

Source: Scottish Government

7. Economic crisis affects not only sectors unequally. Many regions find themselves more negatively impacted by any economic shock than others, leading to much higher regional inequality.

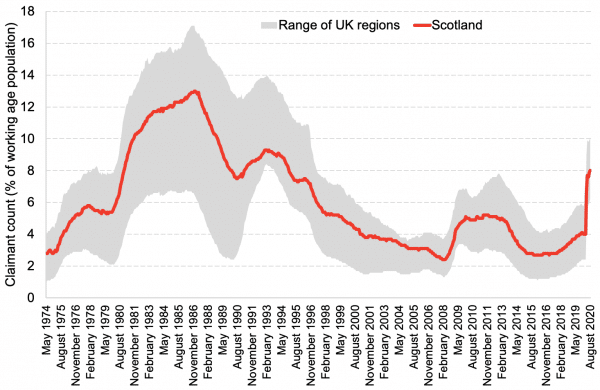

Claimant Count (number of people on Universal Credit and Job Seekers Allowance) has risen sharply in the face of the pandemic. Historically, Scotland has been somewhere in the middle of the pack compared to other regions of the UK, but a 4.1 percentage point increase in August of this year has placed Scotland among the hardest-hit regions of the UK in terms of claims.

Chart 7: Claimant Count as a share of working-age population, Scotland and UK regions, May 1974 – August 2020

Source: ONS NOMIS

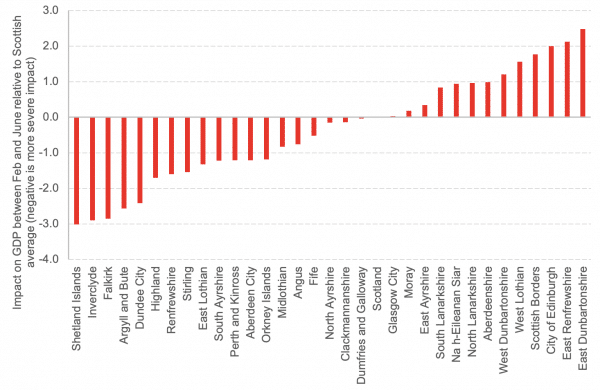

8. Given the variation in sectoral impacts of the pandemic, this has led to some disparity among the effects of the pandemic on local authorities.

Shetland Islands, Inverclyde, and Falkirk were most likely to be among the hardest hit Scottish local authorities due to their heavy reliance on sectors most exposed to lockdown – i.e. the transportation and storage sector (circa 20% of GVA in Shetland Islands and Inverclyde).

On the other hand, East Renfrewshire, Moray and Aberdeenshire are more reliant on sectors where the shock to output has been less significant.

The faster pace of reopening after the lockdown of some sectors relative to others has also contributed to a divergence in developments amongst Scottish local authorities.

Chart 8: Modelled variations in regional economic activity in Scotland based on sectoral employment shares, February to July 2020

Source: Scottish Government, FAI Calculations

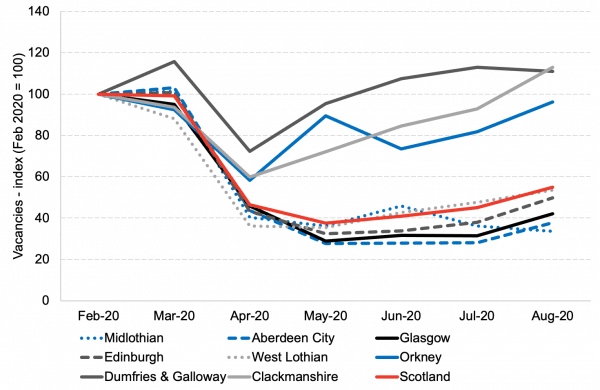

9. The magnitude of the decline in vacancies has also varied amongst Scottish local authorities

The number of vacancies has differed between city local authorities and rural areas, with the number of vacancies falling less during the height of lockdown and recovering to pre-crisis levels in Dumfries & Galloway, Orkney and Clackmannanshire already. However, vacancies in cities have fallen by around 60-70% at the height of lockdown, and recovery has been far slower.

Chart 9: Number of vacancies, February 2020 – August 2020, best and worst-performing Scottish local authorities

Source: Adzuna Labour Market Stats

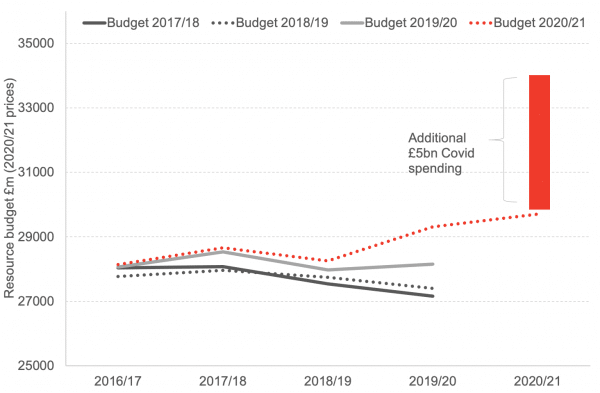

10. There is still significant uncertainty around the outlook for the block grant. There are likely to be further consequentials arising from additional spending on further and higher education, and on skills and employability initiatives in England.

The ongoing crisis has ongoing implications for the Scottish budget. An additional £5.8 billion in resource consequential, stemming from UK Government spending in England, has flowed to the Scottish budget since it was published in February. The UK Government has also guaranteed a minimum uplift in 2020/21 of £6.5 billion of funding related to COVID-19 to the Scottish Government.

With the Scottish Government’s capital funding position increasing by £174 million since February, Scottish Government resource spending is now estimated to be £5bn higher in 2020/21 than anticipated in March this year, whilst revenues from Non-Domestic Reliefs are anticipated to be £1bn lower.

Chart 10: Evolution of Scottish resource budget at successive budget events

Source: Scottish Budgets, various years; Autumn Budget Revisions 2020; FAI analysis

You can read the full commentary here.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.