Today we published our latest Fraser of Allander Economic Commentary.

This short blog summarises our key conclusions in seven bullet points.

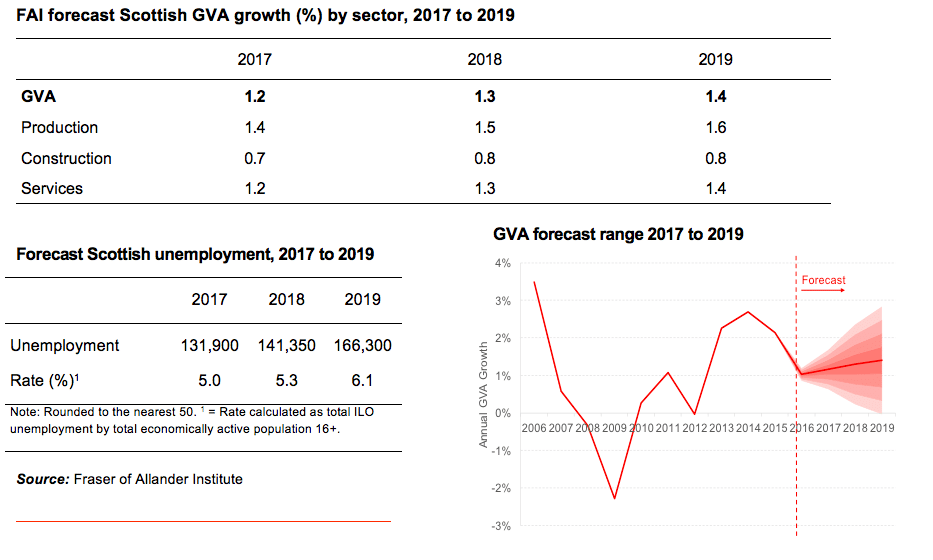

- Growth in Scotland’s economy is forecast to continue through 2017, 2018 and into 2019. The outlook remains challenging by historical standards.

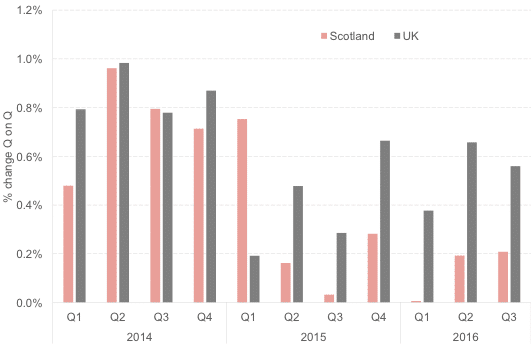

- This outlook comes on the back of growth in Scotland that has been slow for nearly two years now, and much slower than the UK as a whole.

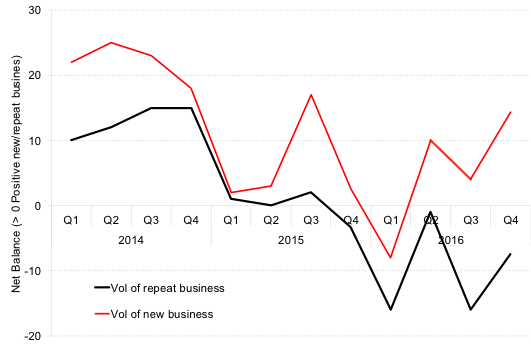

- Some key indicators of business activity – e.g. RBS/FAI Scottish Business Monitor – reported a slightly better end to 2016 in Scotland. This has helped to support a more positive outlook in the near term.

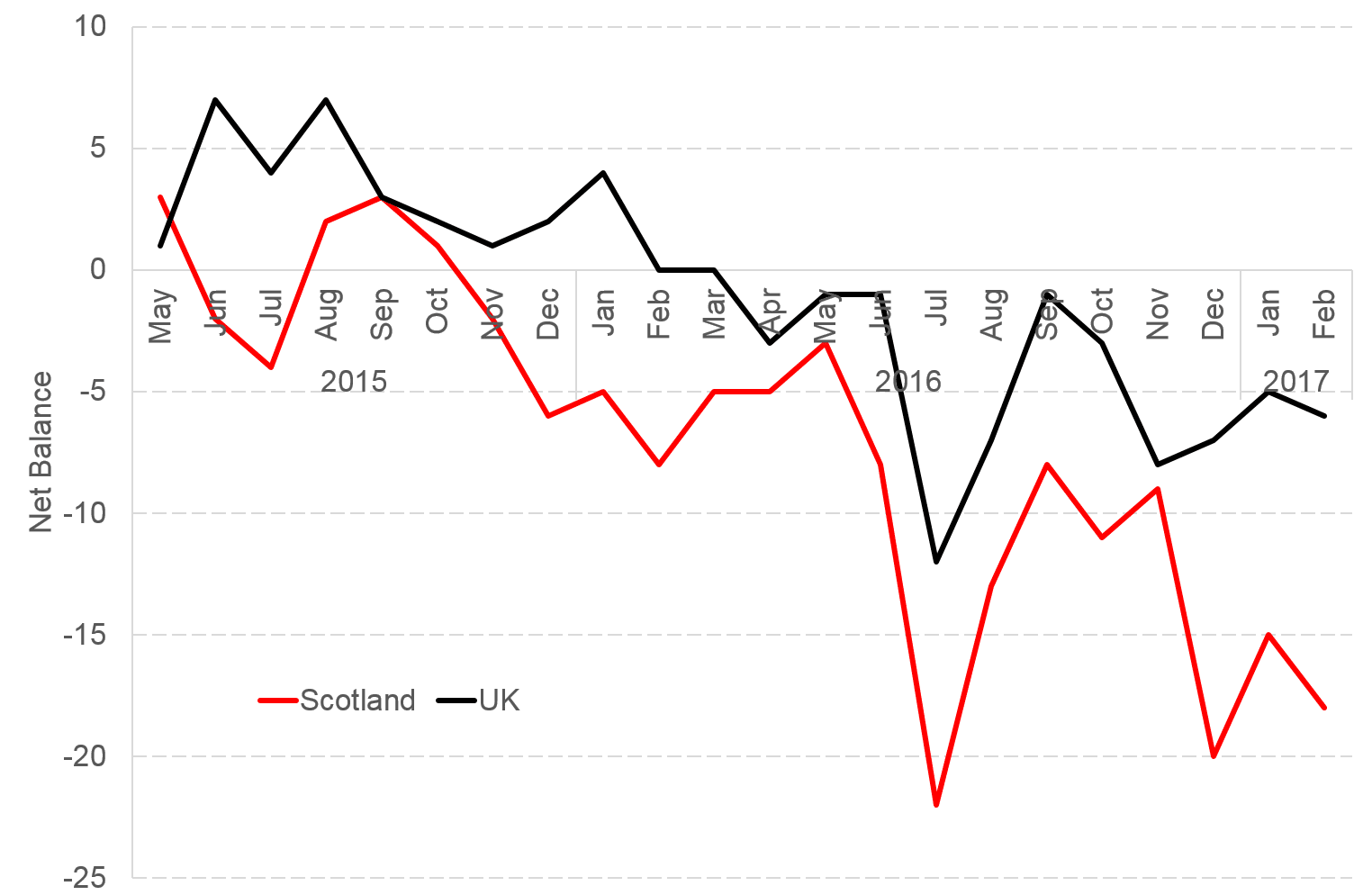

- In contrast, indicators of consumer confidence are weak and getting weaker, and as we can see from the chart below appears to be diverging from these same measures for the UK as a whole.

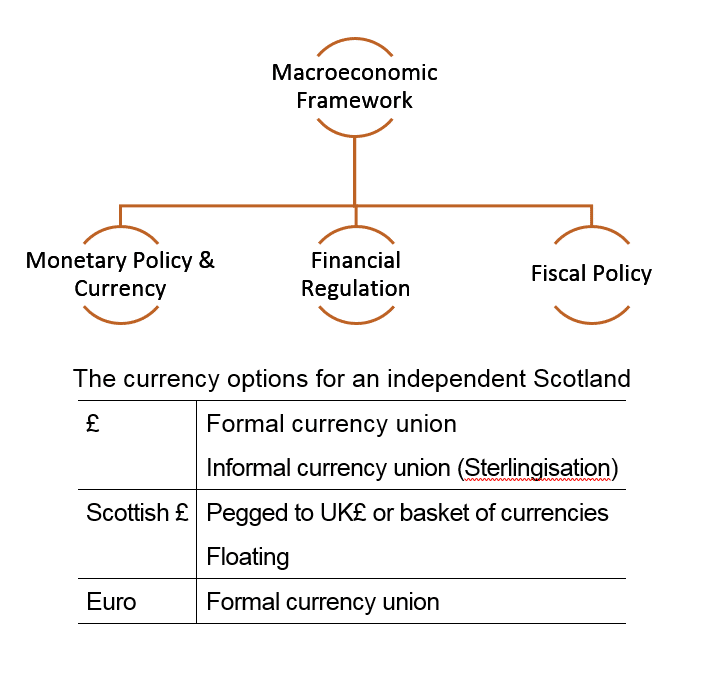

- Indyref2 adds a further degree of complexity to the outlook for Scotland’s economy. The key issues are well known. In the coming months, the Scottish Government will need to set out a robust macroeconomic framework covering the key areas of: monetary policy & currency, financial regulation (including contingency for its banks) and fiscal policy (and crucially, the management of any borrowing and debt that Scotland would inherit).

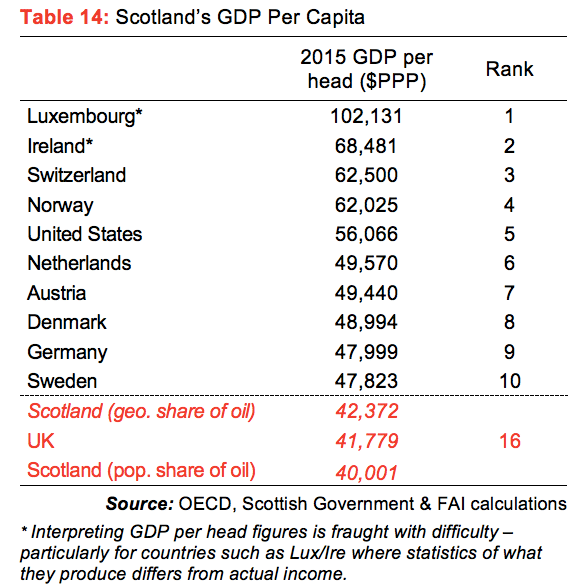

- The Scottish Government will make the case that Scotland is an advanced economy with GDP per head that compares favourably with other nations and that the levers of independence provide an opportunity to do things differently. The UK Government will counter that Scotland now has substantial economic powers, and gains from an established macroeconomic structure and the pooling of resources across the UK.

Few people doubted Scotland could be an independent nation. Debate will once again focus on whether, if it was, people believe that Scotland would be better off or not……

- Whilst the key issues are clear, the arguments this time are likely to be different.

Firstly, in 2014 there was a clear choice between a ‘status quo’ – albeit with more devolved powers – and independence. With Brexit, the debate will be set against the backdrop of two types of economic change.

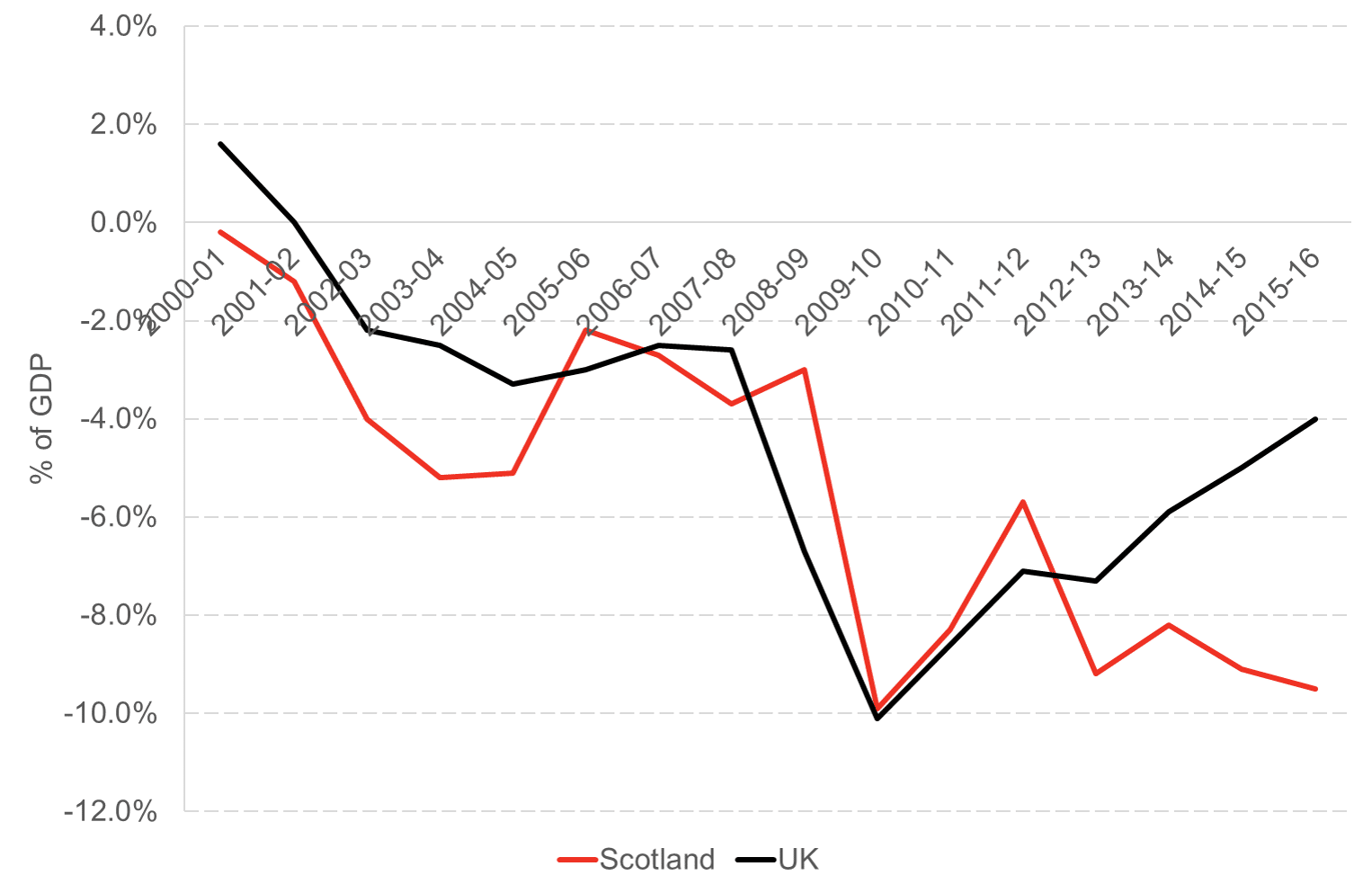

Secondly, it is undoubtedly the case that the recent challenges in the North Sea poses a challenge to any transition to independence. For example, the sharp fall in oil prices has significantly lowered North Sea tax revenues.

The chart below shows Scotland and the UK’s net deficit as a % of GDP

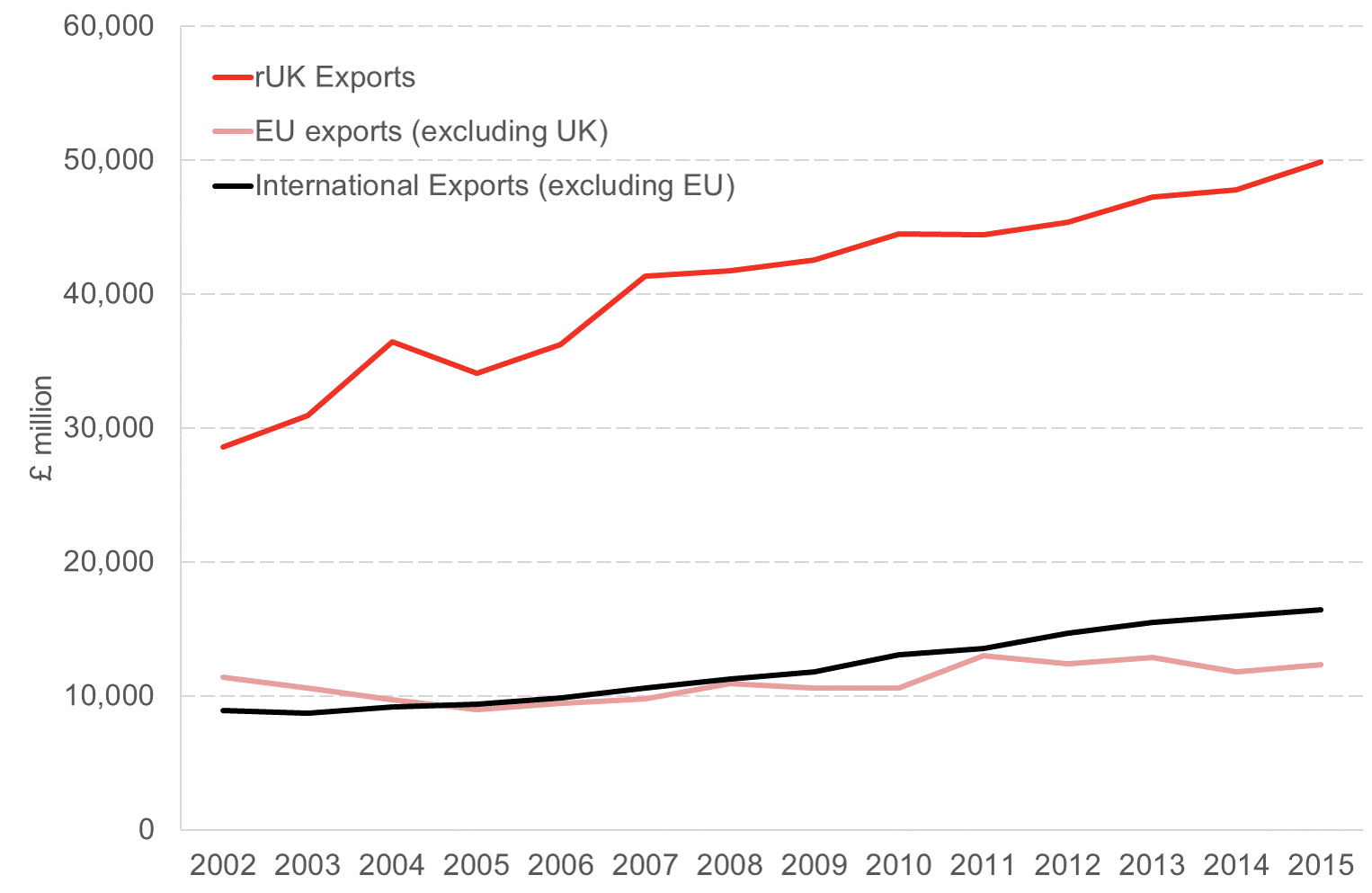

Thirdly, many of those on the ‘yes’ side in 2014 argued that there would be a degree of continuity between the then status quo and independence; e.g. plans to keep sterling, existing financial regulations and for both to be members of the EU. But with the case now framed around Scotland pro-actively taking a different path to the UK (e.g. on EU) will the case be more radical on issues such as currency, financial regulation and fiscal policy? And what might this mean for Scotland’s current and future economic relationships (e.g. with the UK, the EU and internationally)? The chart below shows the destination of Scottish exports since 2002 in £m.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.