Over the past couple of years, researchers at the Fraser of Allander Institute have been working on a project (funded by the Nuffield Foundation*) to explore the effect of class size and composite (multi-grade) classes in Scottish primary schools on pupil attainment. In this article we summarise some of our key findings from this analysis.

If you’re interested in reading the project’s final report, you can read that here and if you want to read the academic paper based on this work this is available as a discussion paper here.

Why look at the effect of class composition and class size?

These are two features that are widely considered to be important determinants of educational outcomes, and have received plenty of attention from parents, academics, practitioners, and policymakers.

Yet, while there is a lot of international evidence on the effects of class size (although we are not aware of any existing empirical evidence for Scottish schools), evidence on the effects of class composition, and more specifically of composite (or multi-grade) classes is limited.

Composite classes are particularly interesting because they allow for the investigation of distinct peer effects on pupils’ attainment.

In composite classes, pupils from different year groups are arranged together to form a single class. This means that some pupils will be exposed to older and more experienced (or conversely younger and less experienced) peers than they otherwise would have been in single-grade classrooms.

In our study, we focus on the aggregate effect of attending a composite class on attainment, along with assessing whether being exposed to older/younger peers in this setting improves (or not) pupils’ educational outcomes.

How common are composite classes in Scotland?

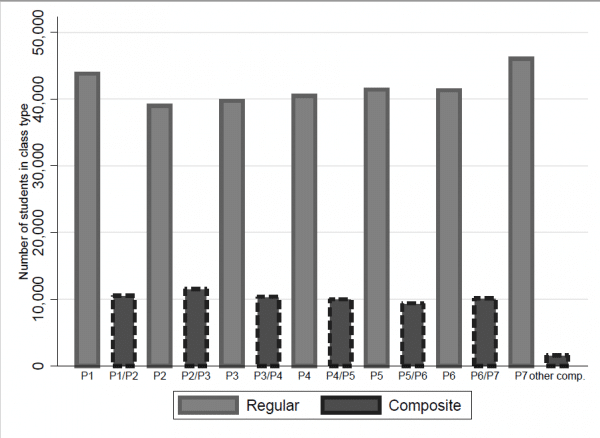

Composite classes are a common feature in Scottish primary schools (see Figure 1).

In 2018/19, nearly one in every five primary school pupils in Scotland were in a composite class.

In Glasgow, Scotland’s most populous city, 84% of schools had at least one composite class in the same school year.

Outside the UK, composite classes are almost exclusively a rural phenomenon, with small schools grouping students from different stages together into larger composite classes. Indeed, most of the empirical literature on the effects of composites has focused on these sorts of rural settings. The fact that composites are so widespread in Scotland, helps us to shed new light on their effect on pupils in a more typical school setting.

Figure 1. Regular and Composite Classes in Scottish Primary Schools (2018)

Why are composite classes so widespread in Scottish primary schools?

There are two related reasons which might explain the popularity of composite classes. First, in Scotland every pupil who lives in a school’s catchment area is entitled to a spot in this school. Catchment areas rarely ever change. Therefore, school enrolment counts depend largely on random fluctuations in a catchment area’s cohort size.

Second, Scotland sets a national policy on binding class size limits in primary schools, which determines the maximum number of pupils in each class at each grade level.

In P1 the maximum class size is 25. In P2 and P3 the maximum class size is 30, and from P4 to P7 it is 33. In composite classes, however, the class size maximum is 25 for all stages.

The combination of fixed catchment areas and fixed maximum class size rules, means that, for example, a primary school with a P2 cohort of 31 pupils will (with few special exceptions) have two options.

The first is to split these 31 pupils across two classes. Physical infrastructure might make this difficult, but regardless an additional teacher would be assigned to this cohort. This, of course, almost doubles the resource requirement.

The second is to try to create composite classes so that the maximum class size rules are not breached. This can potentially provide a solution for schools to meet the maximum class size rules, but at lower resource cost than creating a new single grade class whenever the cohort size breaches the class size limit.

To take a simple example: if intakes for both the P2 and P3 grades are over the class size limit of 30 pupils, they could 1) split both grades to create four single-grade classes or 2) create two single-grade classes and group the remaining pupils into a P2/P3 composite class.

Naturally, the latter option is appealing to schools as it allows them to minimise the number of classes (and related resources) they need to run.

How is it possible to determine the causal effect of composite classes on pupils’ attainment?

Determining the effects of composite classes on pupil outcomes raises the fundamental empirical problem that pupils are not randomly selected into composite classes.

Our data suggest that those pupils who end up in the lower year group of a composite class tend to be on average older, higher attainment pupils from the lower grades.

This means that any ‘naïve’ comparison of the effects of composites by comparing those pupils who are placed in a composite to those that are not, will be biased by differences in the characteristics of students who are placed in composite classes versus those who are not.

Fortunately for us as researchers, the interaction of the class size rules alongside natural variation in school enrolment allows us to utilise quasi-random variation in assignment into composite classes.

This starts with the prediction of the class structure of schools, produced by the local authority and derived from a so-called class planner algorithm. The class planner algorithm calculates the most efficient distribution of students into classes in order to minimise the number of classes that have to be created (and resourced) based on the number of pupils enrolled in each grade.

What this means is that, effectively, small random fluctuations in enrolment counts can trigger the creation of composite classes in some grades, in some schools, in some years, but not in others.

We make use of these random variations in cohort sizes to compare pupils who end up in composites to those who do not but are otherwise similar in observable characteristics.

What data do we use for our analysis?

We use pupil level data spanning from 2007/08 to 2018/19, which links the Scottish Pupil Census (SPC) to other data sources on pupils’ attainment. The SPC contains the population of Scottish primary school pupils. To explore the effect of class size and composite classes on pupil attainment, we use data on teacher-based assessments from the Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) program. Our outcome data are available for schoolyears 2015/16 to 2018/19.

What do we find out about the effect of composite classes?

We find evidence that P1 pupils benefit from sharing a composite classroom with P2 pupils. Specifically that exposure to each additional more experienced peer raises the probability that a pupil performs at the expected level in numeracy by 0.8 to 1.1 percentage points.

Importantly, these benefits do not seem to occur at the expense of P2 pupils as we find no evidence for reduced attainment for P2 pupils in P1/P2 composite classes.

We find evidence of a similar pattern for P4 and P7 pupils, although these findings are less robust.

Moreover, our findings reveal no effect from exposure to older or younger peers on attendance and exclusion rates, nor with respect to attitudes to learning.

What about the effects of class size?

Composite classes tend to be smaller than single-year classes, but in our analysis, we provide evidence that class size is not driving the gains from being in a composite class.

In fact, and in line with most of the international evidence, our results suggest that marginal reductions in class size in either composite or single-year classes offer little return in terms of improved attainment.

It is important to clarify here: we’re not saying that there is no effect of class size on outcomes. It is implausible for example that class sizes of 100 pupils would not affect outcomes relative to a class size of 25 pupils. This is not what we are studying here.

What we are finding here is that there is no evidence that even much smaller class sizes than those prescribed by the maximum class size rules, would lead to improvements in attainment outcomes for pupils.

What are the key policy implications of these findings?

Overall, we find some evidence that exposure to more experienced peers is beneficial to primary school pupils in terms of attainment.

Composite classes, which are very common in Scotland and in numerous other countries, help create these peer effects while at the same time allowing schools to save on resource costs.

This should be good news for Scottish local authorities, because it indicates that the cost savings that composite classes can provide do not come at the expense of pupil outcomes.

Our findings may also help to alleviate parental concerns about composite classes, at least as far as attainment is concerned. The impact of composite classes on other important factors such as, but not limited to, pupil experience and teacher workload was, however, beyond the scope of our study.

Our results also suggest that class structure may potentially be more important for attainment than class size – given that we document very low educational returns from marginal reductions in class size.

Of course, smaller classes may still foster effective learning, allow for easier classroom management and more efficient teaching techniques, and might help with teacher recruitment and retention. Possibly, the reason we find no effect from class size is just that at this stage, all attainment gains from class size reductions have already been realised, and other inputs, for instance peer or teacher quality, are more effective in boosting pupil performance.

An important recommendation is, therefore, that practitioners and policy makers are aware of these other channels when allocating resources.

*Nuffield Foundation grant EDO/43743

Authors

Markus Gehrsitz

Gennaro Rossi

Daniel Borbely

Head of Research at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Graeme Roy

Graeme is Professor of Economics at the University of Glasgow, and formerly Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute