Understanding the local economic impacts of the COVID-19 restrictions is crucial for assessing the potential long-term implications of this current crisis for local communities.

So far, we’ve discussed the sectors most exposed in the crisis and where – at a local authority level – they tend to be concentrated.

A challenge with this approach however, is that it is necessarily relatively broad-brush. There’s often even more variation within a local authority as there is between two different authorities.

In this article, and in an effort to better translate the changes in economic activity that we are observing into what this means for local employment, we combine the latest sector GDP data for Scotland (to August 2020) with the latest small area employment data (for 2019) released last week by the ONS.

Our aim in doing so it to highlight how changes in economic activity at a sectoral level might impact on employment in local areas.

That is not to say that the employment impacts in each sector across areas will exactly turn out to be the same, in reality, some areas may see employment in the same sector change more or less than other areas. Similarly, just because activity (measured by GDP) in a particular sector is down X%, doesn’t mean that employment will turn out to be reduced by the same %, it could be affected more or less. But what the analysis does do is provide an insight into the scale of ‘job vulnerability’ facing local areas from the economy-wide shocks we’re seeing at the moment.

Because sectors of the economy can be geographically quite concentrated, recessions stemming from a particular sector can have quite specific and profound local impacts. The decline of heavy industry for example. However, the pandemic has seen widespread economic declines across sectors of the economy – with few sectors in Scotland now larger than they were at the end of 2019. What we want to highlight in this article is the spatial pattern of job vulnerability implied by these declines in activity across Scotland.

We highlight a few things in this analysis.

- First, given that we have seen activity in almost all sectors decline and stay below its level in December 2019, there are significant numbers of jobs that are vulnerable across all of Scotland.

- Second, while most of the jobs in the Accommodation and Food Services sectors – the sector in the frontline of this crisis – are in cities, the parts of Scotland which are most exposed to declines in activity in this sector are actually mostly rural.

Cities have much more sectoral diversity of employment, and even the substantial declines in activity that we have seen in Accommodation and Food Services are not as notable in terms of overall employment in most urban areas.

What this means is that, if we are to ensure local economic resilience across Scotland, we need to remember the reliance that certain parts of Scotland have on employment in a small number of sectors.

Maps!

What do we mean by small area here? We’re focussing on intermediate datazones, these are summarised as follows:

“Intermediate zones are a statistical geography that sit between data zones and local authorities… [and are] designed to meet constraints on population thresholds (2,500 – 6,000 household residents), to nest within local authorities, and to be built up from aggregates of data zones. Intermediate zones also represent a relatively stable geography that can be used to analyse change over time, with changes only occurring after a Census. …there are now 1,279 Intermediate Zones covering the whole of Scotland.”

The employment data that we are making use of are from the Business Register and Employment Survey, you can find out more details about the data here. These provide good resolution of employment at a local level, focussing on employment in an area rather than the employment of people living in that area –in the jargon, this is a workplace-based measure.

We use these data to understand the composition, by sector, of employment in each of Scotland’s intermediate datazones, and then map changes in employment to changes in overall economic activity.

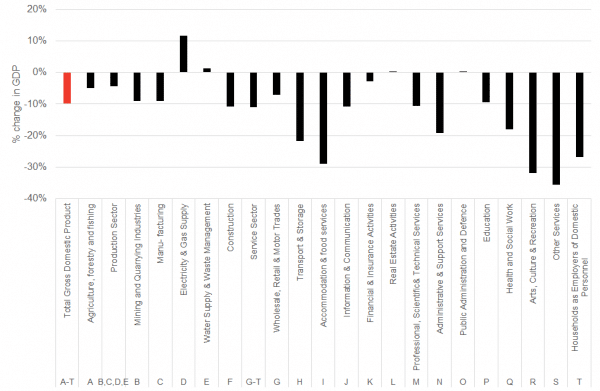

To do this, we make use of the latest Scottish GDP data from the Scottish Government. To provide the most up to date insights, we make use of an experimental monthly GDP series the Scottish Government has started producing earlier this year. This gives us the following pattern of sectoral impacts of the pandemic through to August 2020.

Figure 1: Scottish GDP, Monthly, change Dec 2019 – August 2020

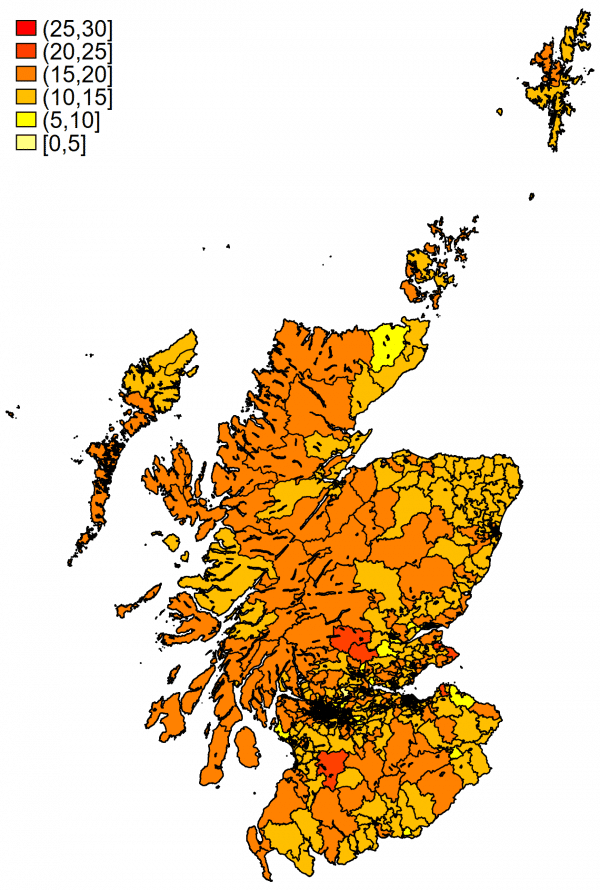

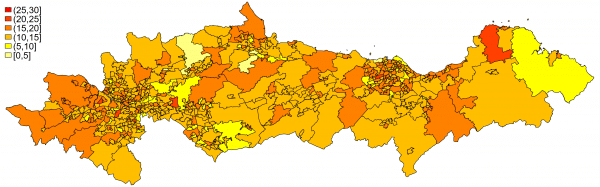

We map these changes in GDP in each sector to local employment in each sector. Note again that this assumes that changes in sectoral GDP and employment are the same (there are obviously reasons why this might be unlikely in practice!). But doing so enables us to visualise (Figure 2) the proportion of jobs in each area that might be vulnerable, given the sectoral composition of employment in that area and what has happened to activity in each sector. Figure 3 presents the same data, but here we zoom in on the central belt.

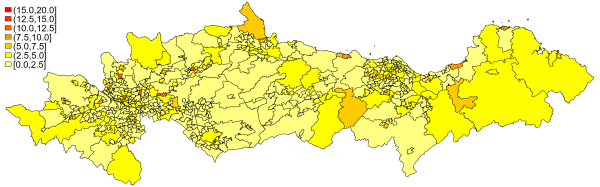

Figure 2: What % of employment in each area are vulnerable?

Figure 3: What % of employment in each area are vulnerable (central belt only)?

What is interesting here is that it is not just cities that have a high share of jobs that might be vulnerable given reduced economic activity.

There are a number of parts even of the central belt with significant jobs that might be vulnerable.

The same is true from Figure 2 across Scotland. Diverse parts of Scotland, from Muthill, Greenloaning and Gleneagles, through to Mosspark in Glasgow, Renfrew South, Largs North, Oban North, and St Andrews North and Strathkinness are amongst the most exposed on this basis.

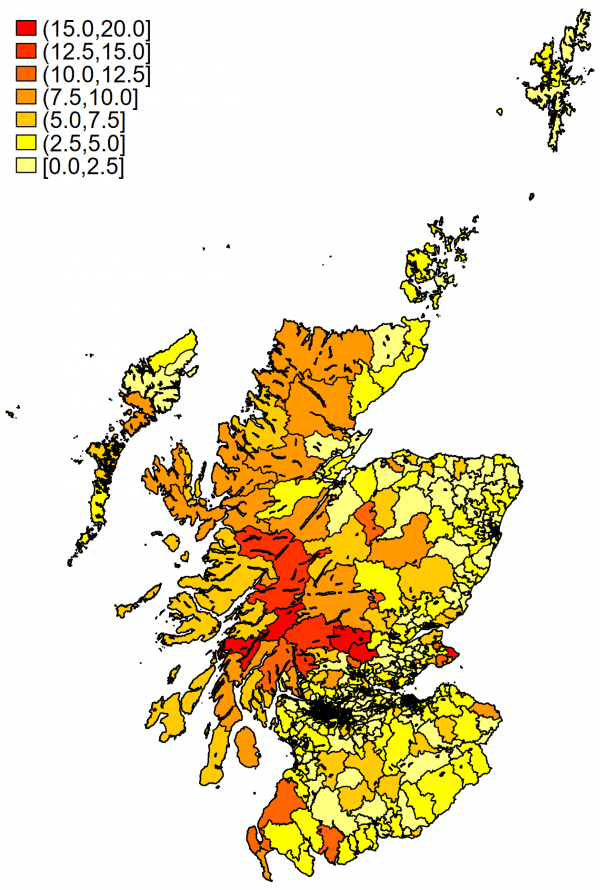

At the same time, we can look at these data on a sectoral basis. Here we only focus on “Accommodation & food services” given its prominence in the current crisis.

Activity in this sector in August was down nearly 30% on its December 2019 level.

Of course, if we map the % change in employment in this sector across intermediate datazones implied by the fall in activity in this sector we’ll end up with a rather boring map! Instead, we explore what this near 30% reduction in employment in this one sector represents in each area as a share of total employment.

This lets us pick out which parts of Scotland are most dependant on jobs in the Accommodation & food services sector.

A simple example may help explain: if an area has 200 jobs, and 100 of them are in this sector, we’d be suggesting that 30% of these, or 30 jobs, are ‘vulnerable’ in this sector. This would represent 15% of jobs in that area. It is this 15% number we map below.

Figure 4: Share of total jobs ‘vulnerable’ because of fall in activity in the Accommodation & food services sector.

Figure 5: Share of total jobs ‘vulnerable’ because of fall in activity in the Accommodation & food services sector (central belt only).

What the last two maps hopefully highlight is that while jobs in the Accommodation & food services sector are important for urban areas, but they are arguably even more important in some non-urban areas.

We can see from Figure 4 that Oban North, Muthill, Greenloaning and Gleneagles, Loch Awe, Comrie, Gilmerton and St Fillans, and Crail and Boarhills are amongst those communities most exposed to declining employment in the Accommodation & food services sector. The reason for this is simple, these areas have a high share of local jobs in this sector (at or around 50%), applying our national decline in activity in this sector since December 2019 of around 30%, translates this into 14-17% of jobs being vulnerable.

Conclusion

It is easy to focus on overall economic impacts of the pandemic or to think of how particular sectors are being affected, without also bearing in mind how important individual sectors can be to local economies and communities.

We’ve tried to highlight this by mapping sectoral changes in activity to changes in local employment in aggregate, and also for the Accommodation and Food Services sector. We’ve seen just how important employment in this sector is to some of Scotland’s rural communities and economies.

It is important as we talk about the challenges facing the Scottish economy and particular sectors that we don’t lose sight of the important role some of these sectors play in local economies.

Sustained shocks to individual sectors can have a particularly acute impact on local economic resilience across Scotland.

Authors

Head of Research at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Graeme Roy

Dean of External Engagement in the College of Social Sciences at Glasgow University and previously director of the Fraser of Allander Institute.