Last week, the Scottish Government published experimental statistics on Scottish Gross National Income (GNI).

This is the latest in the round of developments to widen the coverage of economic statistics in Scotland. The commitment of the Scottish Government to improving the databank of Scottish economic statistics is to be commended. In recent years, this has seen the development of national accounts, a significant improvement in the coverage of GERS, a bringing forward of the publication of GDP and new statistics on Scottish productivity.

Last week’s figures show that Scottish GNI was estimated to be around £27,900 per head in 2016.

Perhaps of greatest interest, the figures also show that Scottish GNI was estimated to equal 94% of Scottish GDP. In other words, there was a net outflow of income from Scotland to the rest of the UK and/or overseas.

What do the figures mean and what do they tell us about the underlying balance of the Scottish (and UK) economies?

What is GNI?

GNI provides a measure of a country’s total national income. It includes all the income earned by a country’s residents and businesses at both home and abroad. It contrasts with GDP which measures the income of anyone within a country’s boundaries, regardless of who produces it.

That is, GNI tends to be based upon ownership, whereas GDP is based on location.

An example might help with the understanding.

Suppose that an overseas firm chooses to invest in Scotland to manufacture a new product. This production will be counted in Scottish GDP. But if the firm’s owners take the profits and repatriate them to overseas shareholders then this will not be counted in Scottish GNI. The people of Scotland don’t benefit from these profits when they are sent overseas.

Of course, the reverse also holds. Should a Scottish firm invest abroad – e.g. take-over a manufacturer in Sweden – and bring back profits to Scotland, then this will add to our GNI.

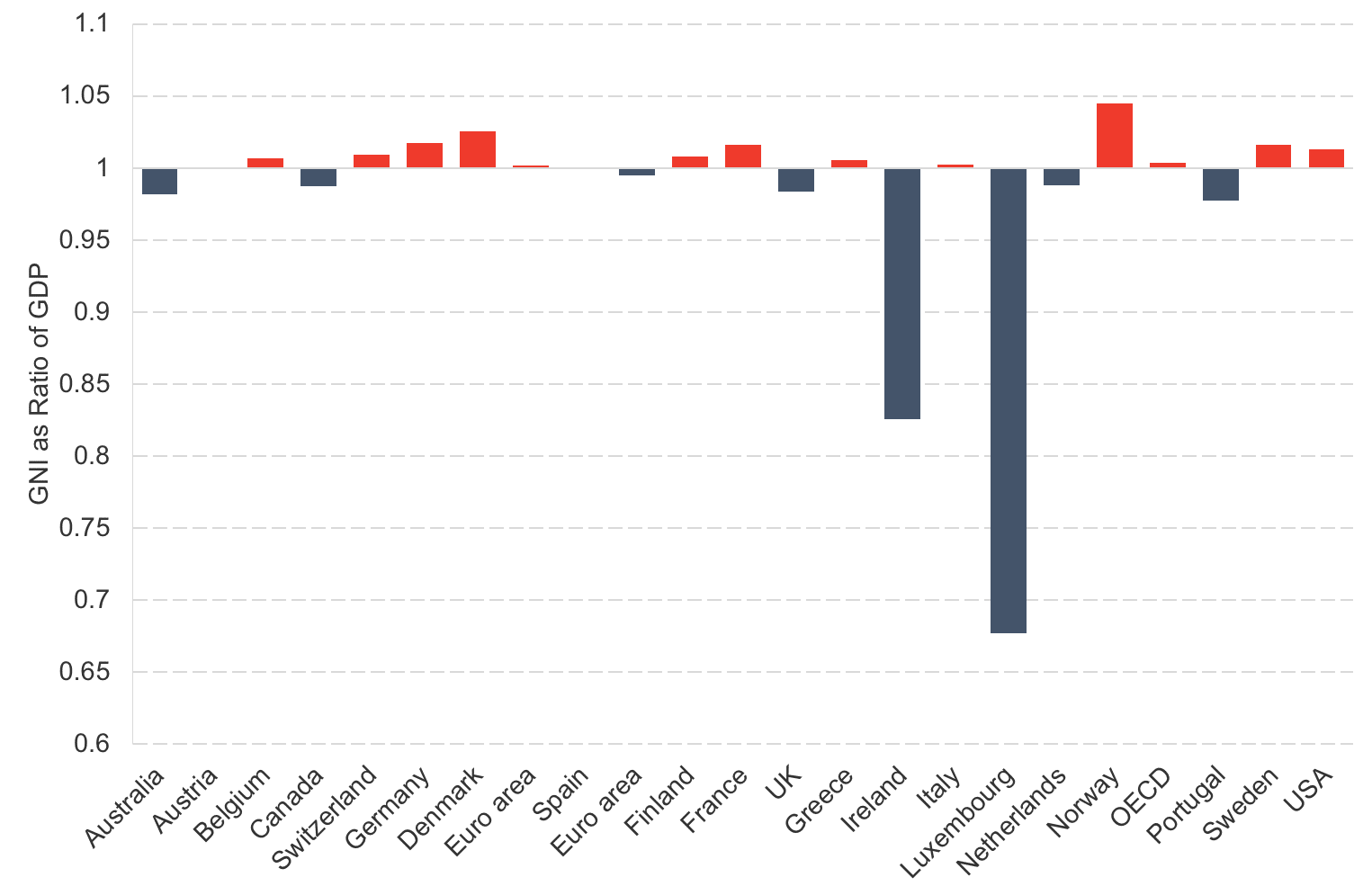

For many countries, GNI and GDP are close to one another. But for others, there can be significant differences.

Take Ireland for example. Ireland benefits from a number of multi-nationals operating out of Dublin. The activity of these firms significantly boosts Irish GDP. But in reality, quite often only a fraction of this activity makes its way into the incomes of the Irish people. Instead, the profits are transferred back to head-offices and investors in the US and elsewhere. Therefore, the amount of actual income earned by Ireland – Gross National Income – is lower.

Figure 1: Ratio of GNI to GDP in select countries

Source: World Bank

The new figures for Scotland

It should be noted that the estimates of Scottish GNI come with a health warning. They are experimental statistics. The Scottish Government have published the methodology and initial results to gauge feedback both on the approach used and interest in the numbers.

Whilst exact data on many aspects of the calculations required for GNI are not available, the estimation methodologies applied by the Scottish Government seem entirely appropriate and the best available at the current time.

That being said, specific point estimates should be treated with a degree of cation – it’s the overall trends that are most relevant.

The latest figures cover up to 2016. They show that –

- Scottish GNI – including a geographical share of North Sea – was estimated at £150.8bn (£27,900 per head) compared to Scottish GDP of £159.9bn (£29,600 per head);

- In other words, Scottish GNI was estimated to equal 94% of Scottish GDP.

This means that there is a net outflow of income from Scotland relative to what is produced here.

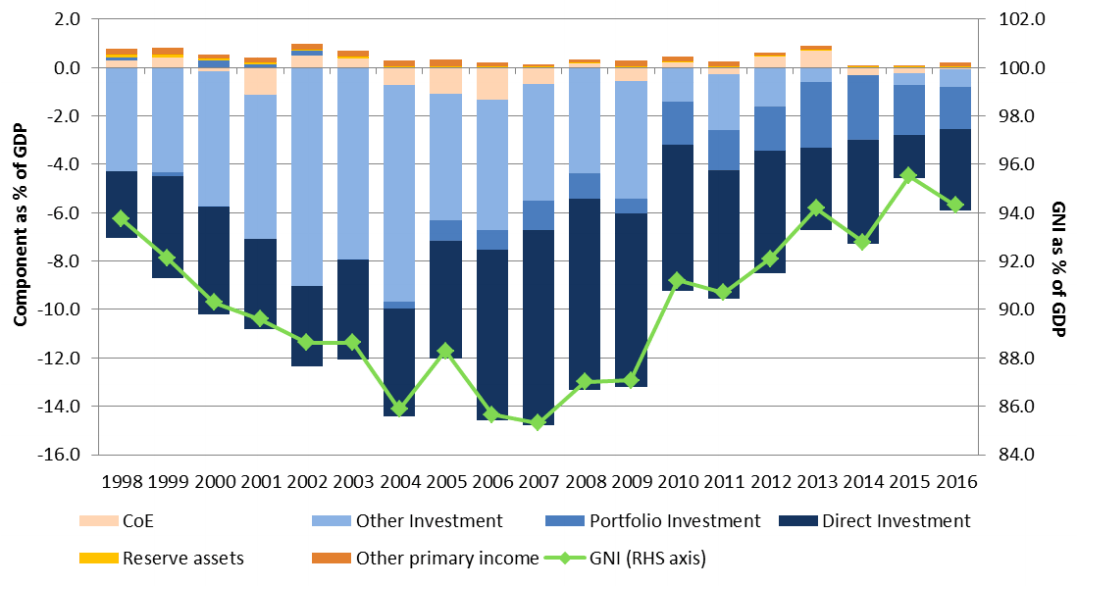

The chart below shows the time path of GNI as a share of GDP over time, broken-down by income component.

Figure 2: GNI as % of GDP and contribution of primary income account components, 1998-2016

Source: Scottish Government

As the chart highlights, through the entire series GNI has been lower than GDP – reaching only 86% of GDP back in 2007.

The statistics show a relatively consistent pattern. Scotland has had a net outflow of income both to the rest of the UK and the rest of the world.

There are a number of drivers of this, but two jump out.

First, Scotland has a large pension, insurance and asset management sector which serves the UK (and global) market so profits will naturally flow to policyholders elsewhere.

Second, the large negative direct investment figure is driven by the predominance of overseas investment in the North Sea (which the Scottish Government estimate accounts for over 40% of the outflow of investment income from Scotland over the sample.

What does this tell us about the balance of the Scottish economy?

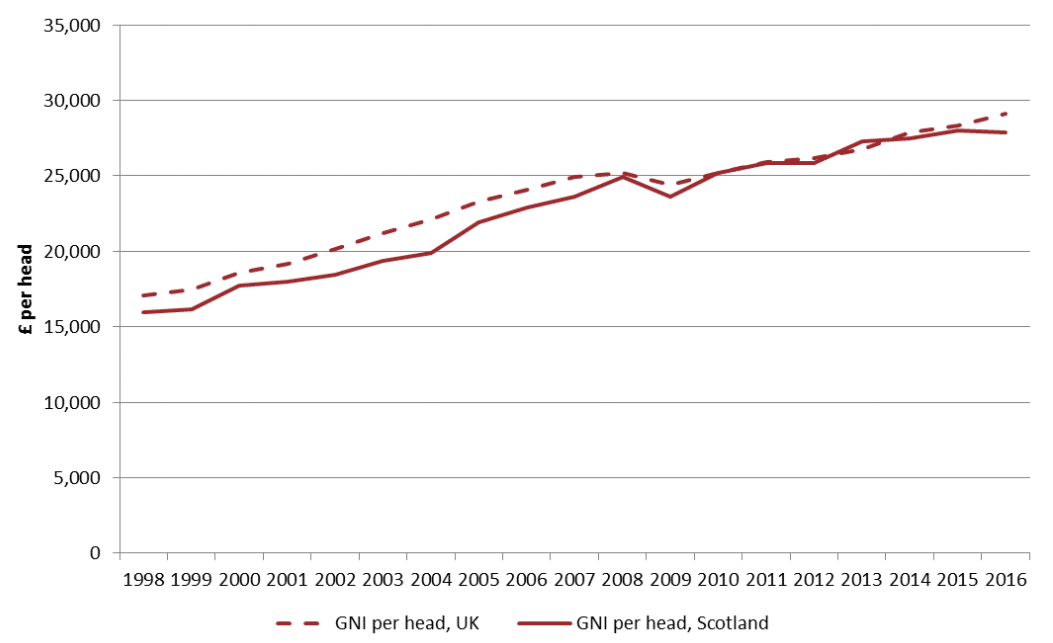

These estimates of GNI confirm that Scotland is a wealthy and prosperous country.

Of course like GDP, GNI is not a perfect measure of ‘economic prosperity’. For example, it doesn’t capture how income is shared in society. That being said, it does still provide a useful indicator of the overall national income of a country.

Like most other indicators of economic performance, the statistics show that Scotland’s GNI per head is broadly in line with the UK as a whole – although unlike in 2013 when the Scottish Government’s first attempt at estimating GNI showed Scotland with a higher GNI per head than the UK as a whole, the reverse is true this time.

Figure 3: GNI per head Scotland and the UK since 1998

Source: Scottish Government

The statistics also reveal some important questions about the balance of the Scottish economy.

As highlighted above, the fact that GNI is lower than GDP suggests that that the amount of national income being retained for the benefit of the people of Scotland is lower than the value of what is being actually produced here.

There are two important interpretations of this.

First, given the importance of the Scottish financial industry to the economy we shouldn’t be surprised that there is a net outflow of income from Scotland. If a Scottish investment firm is successful, then the inflows of investor income that they bring in to Scotland and then turn into a profit should always be lower than outflows.

But second, the figures highlight long-standing debates around the balance of Scotland’s economy and the ownership of the profits made here – see the work of Jim and Margaret Cuthbert over many years. For example, whilst the North Sea has undoubtedly had a major positive impact on Scotland’s economy, the high level of ownership amongst oil and gas operators means that many of the profits flow out of Scotland. This contrasts with Norway.

More generally, the predominance of company headquarters in London and the South East – and in particular, the loss of many Scottish headquarter firms in recent decades – has meant that a higher level of profits flow out of Scotland than has perhaps been the case in the past. Indeed, many of Scotland’s largest firms in major industries – not just oil and gas and financial services but petrochemicals, professional services and whisky – are owned outside of Scotland. So although the products or services may be made here in Scotland, the income doesn’t necessarily stay in Scotland.

This is of course has important implications for debates over economic policy, the overall model that underpins the development of the Scottish (and UK) economies and the constitution…..but we’ll leave all of that for another day.

The publication of these statistics by the Scottish Government should hopefully help make such debates better informed.

Authors

Graeme Roy

Dean of External Engagement in the College of Social Sciences at Glasgow University and previously director of the Fraser of Allander Institute.

Head of Research at the Fraser of Allander Institute