Jeremy Hunt’s challenge in his first budget as Chancellor was two-fold.

First, with the outlook for the public finances having deteriorated substantially since earlier this year – as a result of weaker growth and higher interest rates – he had to indicate how to set out how his plans made a credible move towards fiscal sustainability.

Second, he needed to set out how he would avoid the UK economy slipping into an even deeper recession than the one it is already heading into, and to set out how he would protect households against the high inflation that that is putting a serious squeeze on living standards.

The deterioration in the public finances since March is striking. The size of the deficit in 2023/24 is expected to be £60bn higher than it was in March simply as a result of deteriorating economic conditions, primarily higher borrowing costs. And this weaker underlying outlook is not just shortlived. The weakened economic outlook since March adds around £50bn to borrowing in each of 2024/25 and 2025/26.

How did he respond to his twin-challenge?

In net terms, the policy measures announced today for next year – 2023/24 – are largely neutral, with some additional spending compared to previous plans offset by tax rises (although today’s plans leave in place some significant tax and spending giveaways from earlier this autumn). In subsequent years, tax rises and spending cuts are planned in order to meet, over the longer term, the Chancellor’s fiscal rule that debt should be falling as a percentage of GDP within a five-year window.

By 2026/27, measures announced today will reduce the deficit by £60bn, relative to previous plans.

In the immediate term then, Hunt’s plans for 2023/24 put the emphasis on economic support rather than consolidation. Benefits will rise in line with inflation, the pension triple-lock will remain, there is some additional departmental spending, and a range of support in respect of energy bills will stay in place – including a price cap of £3000 for a typical household, and additional support for those on means tested benefits.

But these measures are not enough to offset the grimmest outlook for living standards on record. Household incomes are forecast by the OBR to fall by over 7% between 2022/23 and 2024/25. This is a larger real terms fall over a two-year period than has been seen previously – including during the aftermath of the financial crisis and subsequent austerity.

Tax measures

This remains a parliament of tax rises. The tax burden as a percentage of GDP will increase from 33% in 2019/20 to 37.5% in 2024/25.

Tax revenue increases in 2023/24 and beyond are largely achieved through already announced measures to freeze various tax and National Insurance thresholds.

A substantial number of further measures were however announced today, designed to raise revenues throughout the remainder of the forecast period. These include a reduction in the tax-free allowance for Capital Gains Tax, and a reduction in the dividend allowance, an extension and increase in the Energy Profits Levy, and a freeze in employer National Insurance threshold.

Newly announced tax policy measures today also included a reduction in the threshold at which the Additional Rate of income starts, from £150,000 to £125,000. This policy will not apply in Scotland, and it will be up to the Scottish Government to decide whether to follow suit.

Our analysis indicates that following this policy in Scotland would bring up to as many as 12,000 additional Scottish taxpayers into the ‘top rate’ in 2023/24, up from 22,000 currently, raising around £40 million in revenue for the Scottish budget. The exact number is uncertain, and may be somewhat less than this, as it will depend in part on the extent to which high income taxpayers respond to the tax change by reducing their taxable income (for example by making more use of tax reliefs).

Spending

The Chancellor did today announce some additional departmental spending relative to plans set out previously, mainly on the NHS and education in England.

This additional spending generates consequentials for the Scottish government – around £800m in 2023/24 and £600m in 2024/25 (technical note: the Chancellor announced Scottish consequentials of £1.5bn over the two years rather than £1.8bn – the lower figure represents the number once various adjustments on the tax side have been incorporated).

Remember that this is the first time that departmental budgets have been ‘topped up’ since the UK government set out its Spending Review in October 2021. Since then, inflation has of course increased substantially.

So, what do these increases in cash resources mean for the outlook for the Scottish resource budget in real terms?

Unhelpfully, that depends to an extent on how you ‘deflate’ cash allocations to real terms. Public spending is normally deflated by the ‘GDP deflator’ which measures price changes of domestically priced goods and tends to reflect price changes faced by the public sector reasonably. At the moment however, there is a wide difference between the GDP deflator and the CPI measure of inflation, since it is the price of imported goods that is increasing. As noted by the OBR, the true impact of inflation on the public sector at the moment probably lies somewhere between what is indicated by the GDP and CPI deflators.

Taking the mid-point of the two deflators, the additional cash allocations for the Scottish budget announced in the Autumn Statement do not fully offset the effect of higher inflation since the previous plans were set out in October last year. In 2023/24, the Scottish resource block grant will be around 3% (£1.1bn) lower in real terms than implied by the October 2021 numbers, and around 2.5% (£900m) lower in 2024/25 than implied by the October 2021 numbers.

Overall

In overall terms this was a statement containing a lot of measures. In net terms these have a fairly neutral effect in 2023/24, with higher taxes on the better off offsetting some additional departmental spending, and without the need to impose lower-than-inflationary uplifts to benefits.

Fiscal consolidation increasingly kicks in in subsequent years, with tax doing a lot of the work but spending restraint also being applied. The implied 1% per annum real terms increases to departmental spending allow the government to say it is avoiding austerity, but it is unlikely to feel that way to some departments.

The Chancellor will hope his plans strike the right balance between fiscal prudence and supporting the economy. But the difficulties of striking the right balance are stark. Despite his measures to support households in 2023/24, that is not enough to avoid large falls in disposable incomes. Yet on the other side of the equation, his plans imply that he will only just meet his target to get debt falling as a percentage of GDP within five years, some two years into the next parliamentary term.

Are you keen for more details? Then please read on for our detailed analysis!

Economic Outlook

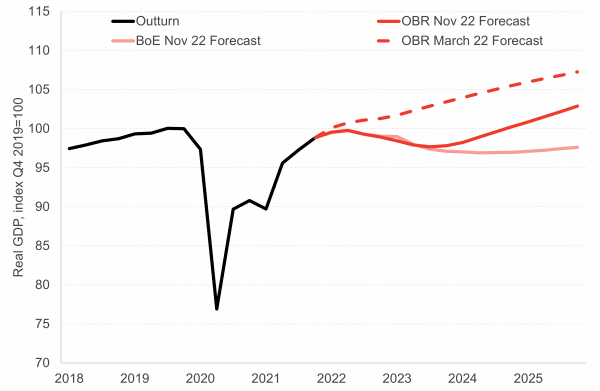

Today, the Chancellor acknowledged the UK is in a recession that is likely to last until Q4 of 2023.

Although this indicates the UK economy is in for a challenging period, the OBR’s forecasts aren’t quite as bad as the Bank of England’s released earlier this month. Here, the Bank of England (BoE) estimated the UK recession would last 8 consecutive quarters, before slowly recovering in Q3 of 2024.

The OBR highlighted a squeeze on consumption and investment as the driving force behind this recession, primarily driven by lower real incomes, rising interest rates and a fall in house prices.

If we look at the components underlying the OBR’s recent GDP forecast, we see that domestic demand, household consumption and fixed investment are all expected to fall in 2023 (by -2.3%, -1.9% and -1.4% respectively). Only strong growth in general government consumption (4.8%) and general government investment (10.7%) appears to be keeping the economy from falling into a much deeper recession.

Chart 1: UK Real GDP Outturn and Forecasts, 2018-2025

Source: OBR, BoE

Inflation

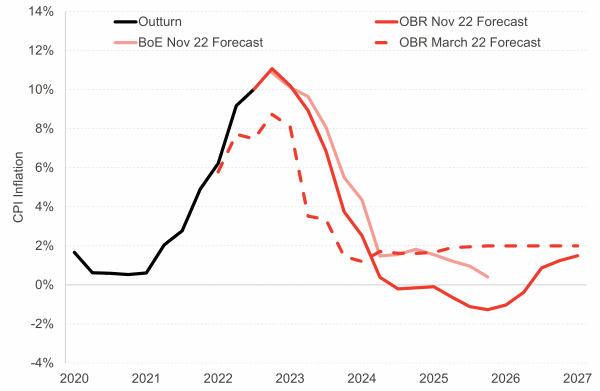

The OBR expects inflation to peak in quarter 4 of 2022 at a 40-year high of 11.07%, a significantly higher level than the 8.73% percent forecasted by the OBR in March but broadly in line with the November BoE forecasts of 10.86%.

This inflation forecasted published today by the OBR expects inflation to be lower than the BoE forecasts in all quarters from Q2 of 2023 onwards. Without the Energy Price Guarantee, the OBR estimates this peak level of inflation could have been two and half percentage points higher.

Inflation is expected to fall in the first quarter of 2023, going below zero towards the middle of the decade, largely driven by falling energy and food prices. By 2027, the OBR expects inflation to return to the BoE’s target rate of 2%.

Chart 2: UK CPI Inflation Outturn and Forecasts, 2020-2027

Source: OBR, BoE

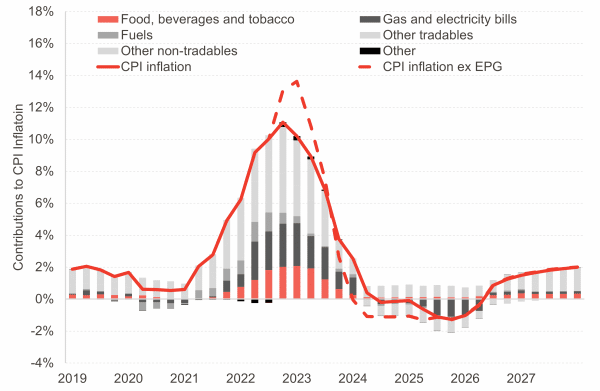

What is driving this CPI Inflation?

Elevated food and drink prices, as well as higher fuels, gas and electricity are behind a lot of the pressures increasing inflation. In September, the prices of food and drink rose 14.5% relative to the previous year. Furthermore, estimates by OFGEM highlight that the price of wholesale gas increased 224% in August relative to its value in 2021.

The Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) limits the contribution of gas and electricity bills to inflation at around 2% in 2023 and 2024. Although the increase of the EPG from £2500 to £3000 will add 1 percentage point to quarterly CPI inflation in the second quarter of 2023.

Chart 3: Contributions to CPI inflation, UK, 2019-2027

Source: OBR

Labour Market

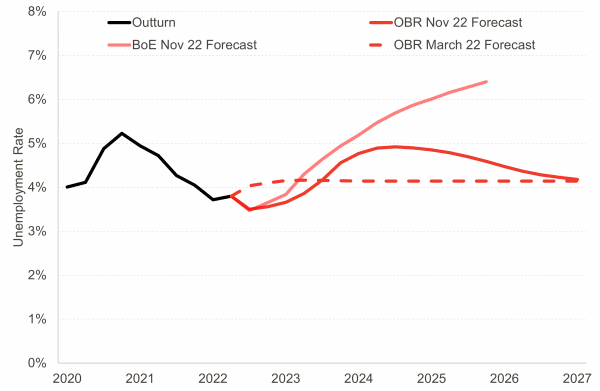

Alongside their depressed GDP forecasts, the OBR unsurprisingly projected a rise in the unemployment rate.

Today, they projected this rate will peak at 4.92% in Q3 of 2024, before falling steadily over the consecutive years to a rate just above 4% in 2027.

This is a considerable deviation from the BoE forecasts released earlier this month, which predicted the unemployment rate would rise year-on-year to a rate of 6.4% in Q4 of 2025.

In light of a particularly tight labour market, the OBR forecasts that the rise in unemployment will lag behind the fall in GDP as vacancies take a while to reduce first before workers are laid off.

Meanwhile, total employment is expected to fairly level between until 2024, before increasing 1% annually from 2024 onwards from 32.7 million in 2024 to 33.6 million in 2027.

Chart 4: UK Unemployment Rate Outturn and Forecasts, 2020-2027

Source: OBR, BoE

In recent months, there has also been a rise in economic activity, largely driven by an increase in the number reporting long term-sickness, which has grown by 169,000 over the last three months (and by 378,000 relatives to pre-pandemic levels).

The OBR are forecasting a decrease in real wages of 1.8% in 2022, 2.2% in 2023, then average of 1.3% growth thereafter. Also announced today was a rise in National Living Wage of 9.7% to £10.42 for those 23 and over, as recommended by the Low Pay Commission.

Fiscal Outlook

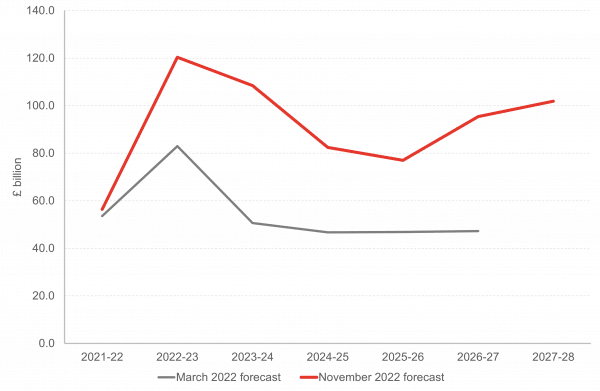

The OBR have forecasted that the deficit this year will be £177bn, up considerably from the £99 billion they were forecasting in March.

In their analysis, they break down the different elements that are contributing to this.

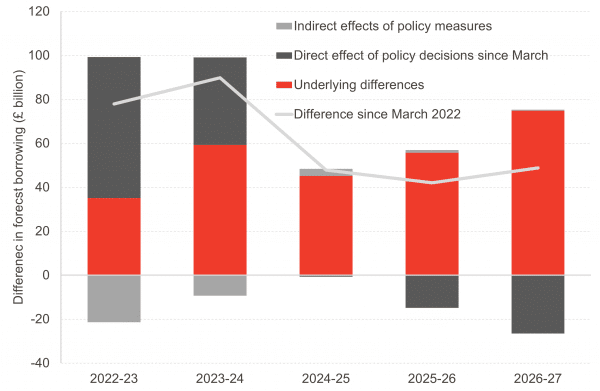

Chart 5: Contributions to the changing deficit

Source: OBR

We can see from this that the lions share of the difference for 2022 and 2023 has been due to policy decisions, mainly the September energy package announced by Liz Truss. However, there is also a big effect from “underlying differences”, which in the main are down to increased debt interest spending.

Chart 6: Debt interest payments

Source: OBR

New fiscal rules were announced by the chancellor today:

- To have underlying debt falling as a share of GDP by year five of the forecast (two years later than the currently legislated-for target)

- To have the deficit not exceed 3% of GDP in that same year.

Two of the four current legislative fiscal rules (which are to have debt falling as a share of GDP by the third year of the forecast and to be in current budget balance) have been missed, and it is not clear if these rules will be swept away.

In their analysis the OBR set out some key risks to their forecasts for the deficit and debt. These included:

- The risk that the Energy Price Guarantee may not be sufficient help for households given its relatively less generous nature from April 2023. In particular, there is currently nothing costed in their projection for any business support measures on energy prices despite a commitment from the Government that the most vulnerable businesses would be protected.

- The risk that the currently baked in fuel duty increase (Of 23%!) does not happen – the tex from the OBR clearly sets out that they do not think this is likely, leaving a hole of around £5.7 billion in the current outlook.

- The risk that there are further one-off support measures to support households and businesses through the period of recession to come.

Despite the large announcements today on tax rises and spending squeezes – a fiscal consolidation of around £55bn – the national debt barely falls over the forecast horizon – falling from 97.6% of GDP in 2025-26 to 97.3% in 2027-28. Given these risks to the forecasts set out above, this gives the Chancellor very little wiggle room to meet even his new fiscal rules.

Social Security

The hotly awaited announcement on benefits uprating resulted in the Chancellor committing to raise benefits in line with inflation, as well as renewing their commitment to the pensions triple lock. Pension credit and the benefit cap have also been uprated by inflation.

The Work and Pensions Secretary is to lead a review of economic inactivity and barriers to entering work – alongside 600,000 people on UC who will be required to meet with work coaches to increase work hours.

An additional £280m has been allocated to DWP to address error and benefits fraud. DWP reported average 4% overpayment of benefit expenditure in 2021-22 (equivalent to £8.6b, highest to date, rose sharply due to Covid), and 1.2% underpayment (£2.6b, same as year prior).

Th Uk Government has also pushed back the managed migration of those on income-related Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) to Universal Credit (UC) (and not receiving Child Tax Credit) to April 2028. This saves the exchequer money: those who gain from moving to UC keep the gain. Those who ‘lose’ are compensated through transitional protection. Delaying the transition therefore saves the Government money.

As part of the announcement on the Energy Price Guarantee (see below), the Chancellor announced additional support for the most vulnerable households.

- One-off payment of £900 to households on means-tested benefits (income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance; income-related Employment and Support Allowance; Income Support; Pension Credit; Universal Credit; Child Tax Credit; Working Tax Credit) across the UK in 2023-24

- One-of payment to pensioner households (those with people over State Pension age) of £300 Pensioner Cost of Living payment in 2023-24

- A one-off Disability Cost of Living Payment of £150 to recipients of extra-costs disability benefits across the UK in 2023-24.

Departmental spending

The big picture on spending is that spending plans are basically the same as set out in last Autumn’s spending review up to 2024/25. After this, there is a tough settlement, which sees total spending reductions of £28bn (1% of GDP) by 2027/28 compared with spending review plans.

Of course, this postpones much of the pain beyond the recession (and, more cynically, the election).

The lack of change in the immediate term for departmental budgets means there is little extra cash to manage higher public sector pay demands & the increased costs of delivering services.

Overall, the tax and spend announcements today have led to an additional £1.5 bn of consequentials for the Scottish Budget.

Personal Tax

The Chancellor announced today that the threshold for the UK additional rate of tax will be reduced from £150,000 to £125,140. They estimate that reducing this top rate of income tax would generate additional income of £420m in 2023/24 and a further £790m in 2024/25 – with those earning over £150,000 paying £1200 more in tax each year.

The implications for Scotland here are interesting. Income tax is devolved, and so the Scottish Government has to decide whether they will follow the UK government’s decision to cut the top rate threshold.

If they do, we estimate that this would increase the number of taxpayers paying the top rate of income tax by 13,000 (to about 33,000) and generate additional revenues of £80m over next two years. This is a significantly smaller revenue generator for Scotland compared to the UK, given the much smaller share of the population in Scotland that pay the top rate of income tax.

This means that even if the Scottish government do decide to follow suit, then Scotland is likely to face a negative net tax position due to this change, as the deduction off the block grant is likely to be larger than additional revenues given the higher earnings in England.

This does not necessarily mean that the Scottish budget is worse off: if the UK government decides to spend additional revenues on health and social care or education, then Scotland would receive higher funding via the Barnett formula.

On other personal taxes, and in line with previous announcements, the personal allowance, national insurance and inheritance tax thresholds will be frozen – but now for a further 2 years up to 2027-28.

Dividend income allowance was cut from £2000 to £1000 in 2023/24 and further down to £500 in 2024/25, and the capital gains tax free allowance down from 12,300 to £6,000 in 2023/24 and down further to £3000 in 2024/25.

Windfall taxes

Gas and electricity prices have risen to eight times their historic average and energy prices are still the largest single driver of current UK inflation levels. Today’s fiscal statement has increased the Energy Profit Levy from 25% to 35% (beginning January 1st, 2023) and extended the levy from December 2025 to March 2028. Including a 30% corporate profit tax and a 10% supplementary charge on North Sea operations, this brings the total tax rate on energy company profits to 75%. The original goal of this levy was partially to fund the cost-of-living package, originally announced in May 2022, although the OBR predicts that the levy will raise more than these support payments cost.

The Chancellor outlined that “windfall taxes” need to be temporary and avoid deterring investment. To encourage investments, corporations can claim a 91p tax savings for every £1 of profit they invest in UK energy. This may ultimately create a confusing incentive structure: corporations may choose to invest rather than curb profits, limiting the effect of the windfall tax on reducing consumer prices.

An additional levy of 45% for electricity generators was announced, also beginning January 1st. This applies to extraordinary profits above £10 million for generators producing above 100GWh at an output price above £75/MWh. This should act to limit non-oil and gas energy generators from profiting on current high energy prices. This is a temporary levy, with forecasts showing tax earnings through 2028. However, the exact length of the levy is unclear. Prior to this statement, there was some speculation that the government would announce some form of revenue cap, in line with EU policy.

In total, the two levies are expected to earn around £14bn next year, and average £8bn a year over the next four years. This is up from £5.5bn a year from in the original announcement.

In addition to increased windfall taxes, the Chancellor announced a long-term energy strategy with two key focusses: energy independence and energy efficiency. A £700 million investment was announced for a new nuclear power plant at Sizewell C to facilitate this move towards greater energy security within the UK. This is the first state backing for a nuclear project in over 30 years. The improved energy efficiency strategy aims for a 15% reduction in energy consumption from buildings and industry by 2030. An additional £6 billion investment was announced for 2025 to 2028, in addition to the £6.6 billion committed in this Parliament. A new Energy Efficiency Taskforce will be responsible for the required increases in energy efficiency across the economy.

Other tax announcements

Vehicle Excise Duty on Electric Vehicles

An unexpected policy decision set out by the Chancellor was the introduction of Vehicles Excise Duty on electric vehicles. Starting on the 1st of April 2025, zero emission electric cars registered on or after this date will be liable to pay the £10 first year rate. The following year the rate will increase by £155 to the standard rate of £165.

The Chancellor is betting that demand for electric vehicles will continue to rise despite this measure reducing the incentive to make the switch to electric vehicles.

Fuel Duty

Keen observers will have noticed there was no mention today of fuel duty rates.

The current PM and former Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s temporary decrease of 5p per litre is due to expire in late-March next year.

Baked into the OBR’s forecast of public sector borrowing is the assumption that the fuel duty rate will increase by 23% in 2023. An increase of this size would generate £5.7 billion in tax receipts and increase the price of diesel and petrol by around 12p per litre.

This would be the first cash terms increase to fuel tax in over a decade. The recent history of freezing fuel duty rates combined with the Government’s goal of pulling down inflation likely lies behind the OBR’s decision to highlight the policy as a potential risk to their forecast.

Going forward there will be pressure on the Chancellor to hold off increasing fuel duty come spring – potentially driving a wedge between the OBR’s forecast and the realised level of public sector borrowing.

Business-related announcements

In our latest quarterly Scottish Business Monitor, we asked Scottish firms what they wanted to see in the UK Government’s Medium-Term Fiscal Plan, announced today, and the Scottish Government’s upcoming budget, due on the 15th of December.

More than a quarter of firms that responded mentioned VAT and/or other tax cuts. Stability was also mentioned by 7% of responding firms, with 6% mentioning business rates. So – what was there in these announcements for businesses?

- The secondary threshold for employer contributions to National Insurance will be fixed at the current threshold of £9,100 from April 2023 until April 2028. This measure raises over £25bn in government revenue from 2023/24 – 2027/28. This is by far the most significant measure announced today in terms of business taxes.

- The longstanding freeze on the £85,000 VAT registration threshold will now be maintained at their current levels until 31 March 2026 – raising £1.5bn from 2024/25 – 2027/28. This has obvious implications for SMEs, particularly given the ongoing inflationary pressures that would push a number of small businesses past this threshold.

- Finally, there is no sign of the Energy Bill Relief Scheme (EBRS), which provides energy support for businesses between 1 October 2022 – 31 March 2023, being extended beyond 2022/23. This support is estimated to cost the UK Government £18.4bn in 2022/23. It is important to note that it is not just businesses that are supported through this scheme, charities also have been given support on their energy bills through this funding. The OBR notes that the “Government has said that vulnerable businesses will continue to be helped” beyond March next year however, we could not find any costings of this in the Treasury’s figures. The treasury notes that they will lead a review of the EBRS to determine the level of non-domestic energy support required beyond 31 March 2023.

Business rate powers are devolved to the Scottish Government however, it is worth noting the significant changes announced in today’s UK Government Budget as SG may feel pressure to provide similar support for Scottish businesses, particularly on the retail, hospitality and leisure relief and the rate freeze.

Energy Price Guarantee

Energy prices had previously been frozen for two years from October 2022 in the “mini budget” at £2500 per year for the typical household. While the price cap is remaining in place this winter it has been made less generous in 2023 and onwards. From April, energy prices will be capped at £3,000 instead of the prior £2,500.

What does this mean for households?

Annual energy bills will be increasing from April 2023 onwards.

The typical household can expect their annual energy bill to increase from £2,500 currently to £3,000 in April 2023 and remain at this point for another twelve months. Note that your own household bill may be higher or lower than the typical bill depending on energy use.

In addition, the Energy Bills Support Scheme, which is currently reducing each household’s bill by around £66 per month will be finishing in March 2023. For example, if your household electricity and gas bill was £250 in October 2022, you should expect your bill in October 2023 to be around £366*.

If your household electricity and gas bill was £200 in April 2022, you should expect your bill in April 2023 to be £304 **.

* £250 x 1.2 + £66 = £366.

** £200 x 1.52 = £304.

We’ll be putting out more analysis on the Energy Price Guarantee tomorrow, so look out for that!

Authors

Mairi is the Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, she was the Deputy Chief Executive of the Scottish Fiscal Commission and the Head of National Accounts at the Scottish Government and has over a decade of experience working in different areas of statistics and analysis.

Emma Congreve is Principal Knowledge Exchange Fellow and Deputy Director at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Emma's work at the Institute is focussed on policy analysis, covering a wide range of areas of social and economic policy. Emma is an experienced economist and has previously held roles as a senior economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and as an economic adviser within the Scottish Government.

David Eiser

David is Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute

James is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. He specialises in economic policy, modelling, trade and climate change. His work includes the production of economic statistics to improve our understanding of the economy, economic modelling and analysis to enhance the use of these statistics for policymaking, data visualisation to communicate results impactfully, and economic policy to understand how data can be used to drive decisions in Government.

Adam McGeoch

Adam is an Economist Fellow at the FAI who works closely with FAI partners and specialises in business analysis. Adam's research typically involves an assessment of business strategies and policies on economic, societal and environmental impacts. Adam also leads the FAI's quarterly Scottish Business Monitor.

Find out more about Adam.

Ben is an Economist Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute working across a number of projects areas. He has a Masters in Economics from the University of Edinburgh, and a degree in Economics from the University of Strathclyde.

His main areas of focus are economic policy, social care and criminal justice in Scotland. Ben also co-edits the quarter Economic Commentary and has experience in business survey design and dissemination.

Hannah is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in applied social policy analysis with a focus on social security, poverty and inequality, labour supply, and immigration.

Rob Watts

Knowledge Exchange Associate at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Calum Fox

Calum is an Associate Economist at the Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) and a Researcher at the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP). He specialises in economic modelling and trade, and holds an MSc in Economics from the University of Edinburgh.

Kate Milne

Kate is a Knowledge Exchange Assistant at the FAI working across a number of project areas. She has a Masters of Science in Economics from the University of Edinburgh and a bachelor’s degree in Economics from the University of Strathclyde. Kate is also the Outreach Coordinator at the Women in Economics Initiative which aims to encourage equal opportunity and improve representation in the field.

Allison is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in health, socioeconomic inequality and labour market dynamics.

Ciara is an Associate Economist at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She has a broad research experience across different areas including poverty and inequality, the voluntary sector, health, education, trade, and renewables and climate change. Ciara has an MSc in Applied Economics (Distinction) and a first-class BA Honour’s degree in Economics and Finance, both from the University of Strathclyde.

Jack is an associate economist at the Fraser of Allander Institute.