Conditions in the labour market are a key indicator of the underlying health of the wider economy, and the labour market is a key driver of economic prosperity for people across the country.

In this article, I review the latest labour market data, put it into a historic context, discuss the role that policy has played in shaping labour market outcomes through the pandemic, and set out some of the issues and challenges that lie ahead.

Labour market powers

Government plays a key role in shaping economic outcomes in the labour market; from providing social safety nets for those who become unemployed or who cannot find work, through to providing skills and training to support people to secure a job (or get a better job).

In Scotland, responsibility for several key policy areas affecting the labour market is devolved, while a number of headline policies remain UK wide.

The devolved economic drivers, controlled by the Scottish Parliament, are mostly focused on the longer-term drivers of labour market outcomes. These include things like investment in education, skills and employability. But there are broader levers Holyrood controls that will have an impact too on labour market outcomes, such as powers over income tax (although as set out here, the fiscal framework complicates their use) and areas such as transport and housing which all impact upon how easy it is for someone to find work.

Powers over labour market regulation, for example, employment rights, the minimum wage and job seekers allowance are reserved to the UK Parliament. The UK retains primary responsibility for macroeconomic stability too, a key driver of the labour market.

With the devolution of welfare powers in recent years, some newer policy levers are beginning to be controlled from Scotland.

It’s not just in specific policy priorities that the Scottish Government has influence over the labour market. Through government procurement and so-called ‘convening’ abilities (for example bringing together businesses, trades unions and others to try to agree common objectives) there are indirect channels through which the government can have significant influence.

A good example of this sort of activity is the Scottish Government’s ‘Fair Work’ focus through the Fair Work Convention.

The latest data

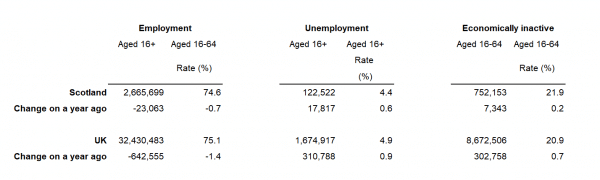

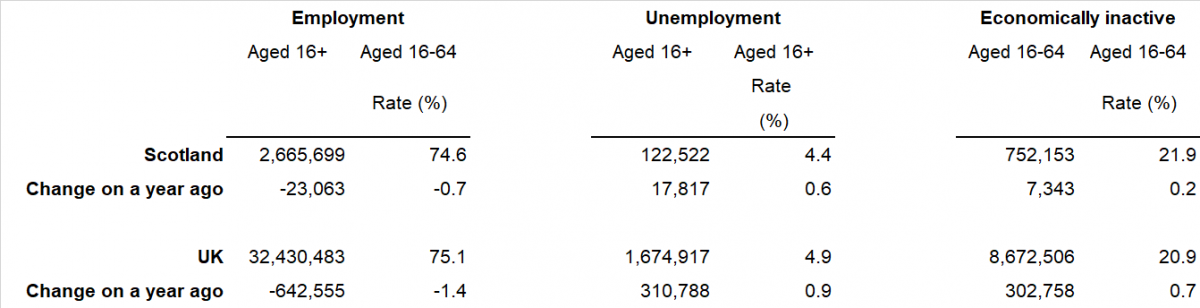

Given the scale of the shock to the economy caused by the CoVid public health emergency, you might expect that we’ve seen significant increases in unemployment. But so far, we haven’t really seen much movement in headline labour market indicators across the UK. Table 1 below provides a snapshot of the headline labour market indicators in the UK and Scotland.

Table 1: Headline labour market measures, UK and Scotland

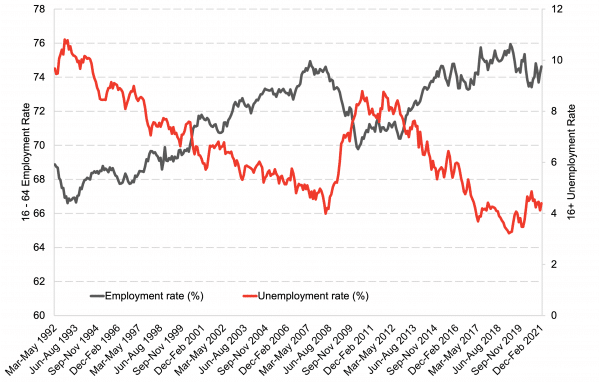

Looking back over the last thirty years (Figure 1) we can put the current low rates of unemployment and high rates of employment into a historic perspective. In the period leading up to the pandemic, the Scottish labour market was posting near-record low unemployment and high rates of employment.

Figure 1: Scottish employment and unemployment rate

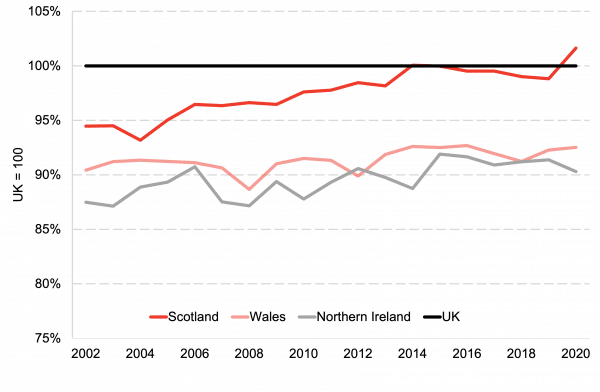

Meanwhile, wage growth across the UK has been disappointing. That said, for full-time workers, we’ve seen gross weekly pay in Scotland catch up with that of the UK as a whole by 2014 and remain around that level thereafter (Figure 2). Again though, this is in a context where pay growth for the UK as a whole has been weak post the global financial crisis, so isn’t really much to shout about.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that headline statistics on pay can be driven by changes in the composition of those employed, and so are not best looked at in isolation. We’ve seen some statistics showing faster average pay growth in recent months, but an important driver of this is a loss of lower-paid jobs, rather than increases in pay for those in employment. This so-called compositional effect is not a sign of a robust labour market.

Figure 2: Gross weekly pay for full-time workers, % of UK

At the same time as we’ve seen these, on the face of it, positive signals about the health of the labour market there has been rising concerns about the quality of work.

In particular concerns about less secure work, such as temporary and zero-hour contracts. But also, about hours-based underemployment, which is where people working fewer hours than they wish. What do we know about these issues?

Data on the number of people on zero-hour contracts in Scotland can be found here. These show that this form of employment affects a very small share of those in work, 2.8% of people, or 72,000 people. This tends to be slightly lower than the UK (3% at the moment).

Data for the UK as a whole show that younger workers, and those working in certain sectors like retail and accommodation and food, are much more likely to be on zero-hour contracts than others. While in aggregate it only affects a small portion of the labour force, for some segments of society these are much more common.

On underemployment, a good source to track this issue is the Underemployment Indices produced by the Resolution Foundation. You can access these here. This is a broader measure than just those in work who want to work more hours, capturing also those who are unemployed. But the clear picture from these data are that while underemployment is rising again, it is still well down on its peak in the early 2010s. In a recent briefing paper, we looked at underemployment in more detail. You can read this piece here.

Finally, it is worth noting that some criticise the headline employment rate on the basis that someone working one hour a week is classed as being employed. This is true, but it is also worth noting that the number of people estimated to be working very few hours is very small and hasn’t changed much over the past 30 years. You can read more about this issue here.

The labour market in the pandemic

So, with unemployment apparently remaining low even through this crisis is there anything to worry about?

In short, yes. The traditional data on the labour market is being skewed by government policy support – most notably furlough.

It is far better to look at new and, at this point, still experimental data being produced which track payroll employment (in essence the number of people registered to pay Pay-as-you-earn (PAYE) income tax).

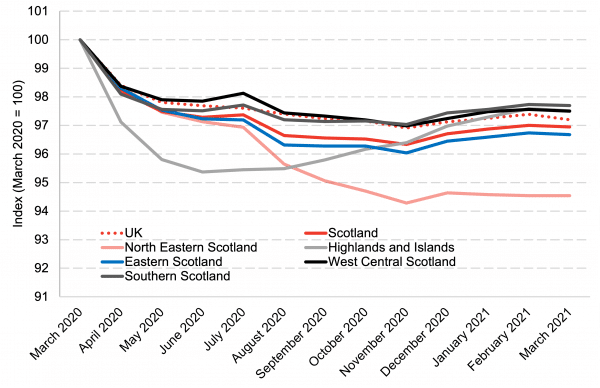

These have enabled a slightly timelier and more granular understanding of the labour market through the pandemic. Figure 3 shows the evolution of payroll employment in Scotland through the pandemic.

Figure 3: PAYE payroll employment

While the payroll employment is down everywhere since March 2020, and the impact in Scotland is broadly in line with that of the UK as a whole, what has been happening in the North East and Highlands and Islands stands out.

The North East of Scotland in particular has been hit by two shocks: a downturn in the Oil and Gas sector and the pandemic. In the Highlands and Islands the pandemic led to significantly lower employment in summer 2020, and while this has recovered somewhat, the summer ahead – and the strength of tourism demand – will be key to the longer-term recovery of the economy in the Highlands and Islands.

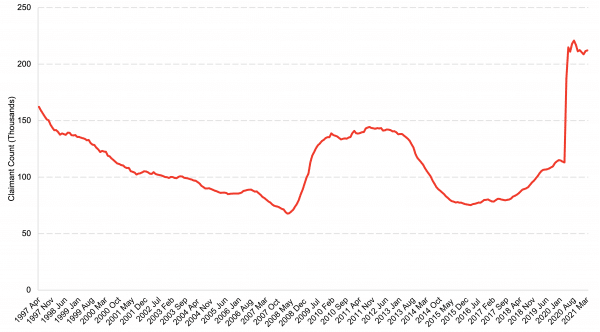

Another key data source to enable us to track the effect that the pandemic is having on the labour market is data from the welfare system. In particular the number of people claiming unemployment related benefits.

Sometimes referred to as the ‘Claimant Count’, in the UK this is complicated by the structure of Universal Credit which provides support to some people working very low hours or on very low pay who are required to search for work. Thus not everyone in the claimant count is unemployed.

Through the pandemic, we have seen a significant increase in the number of people claiming unemployment related benefits (Figure 4). 212,000 people were claiming unemployment related benefits in Scotland in March 2021, up 99,000 on the same point in 2020.

Figure 4: Claimant Count

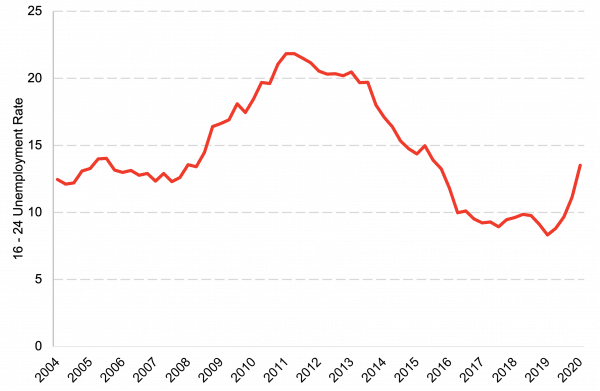

One group in the labour market who have been particularly affected by the economic effects of the pandemic are younger workers. So-called youth unemployment in Scotland has risen significantly through 2020, reversing recent trends of falling youth unemployment. Figure 5.

The main explanation for this is that the sectors which have been hardest hit by restrictions through the pandemic are those where young people tend to work, in particular retail and accommodation and food services.

Figure 5: Youth (16 – 24) Unemployment Rate

While the youth unemployment rate remains lower than its post-financial crisis peak – a key concern is that we’re already seeing significant increases in the unemployment rate while support schemes remain in place.

CoVid support and response

The UK Government’s furlough support scheme will likely go down as one of the most effective economic policies that has been brought forward to combat an economic crisis.

The speed of implementation, its scale and the scope of this programme was truly impressive.

While not perfect in its design, it has undoubtedly protected many households from stark economic realities. In total, nearly 10 million jobs had been furloughed in the UK by the end of 2020.

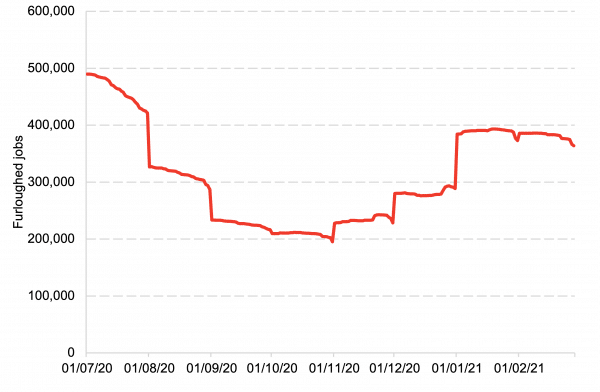

The most recent data show that at the end of February 2021 over 360,000 jobs were furloughed in Scotland. Figure 6 highlights how the number of jobs furloughed in Scotland has varied since summer 2020. In particular how the number of jobs furloughed reduced as restrictions were eased, although barely fell below 200,000 even with significant easing of restrictions.

Figure 6: Furloughed jobs in Scotland

In a similar way, support for the self-employed, while inherently more difficult to do given the more complex nature of self-employment has provided significant support to a huge number of people. However, some still missed out on support through this scheme.

At the same time, we also saw enhancements to Universal Credit brought forward by the UK Government, raising payments by £20 a week.

As set out earlier, the devolved levers in this area focus more on the longer-term drivers of the economy, and in particular on skills and education. Once the emergency levers of support are lifted at the UK level, the focus of attention will very much shift to the next Scottish Government.

The Scottish Government’s Advisory Group on Economic Recovery report released in Summer 2020 identified a ‘Young Persons Guarantee’ as a key mechanism to support young people who had faced a particularly challenging period through the pandemic with the shutdown of much of the hospitality and retail sectors where many younger people tend to find work. This was not a new idea, being built on a policy implemented in the last recession (‘Opportunities for All’), and its success depends critically on delivery.

The issues that lie ahead

The outlook for the Scottish labour market contains a number of challenging issues through the short, medium and long term. This is not an exhaustive list, but two or three issues that are likely to become important through the next parliament.

Short-term

- The ending of the furlough support scheme, as currently planned for the end of September, will be a key moment for the Scottish labour market. With nearly 200,000 jobs still furloughed even with the easing of restrictions in 2020, and over 360,000 jobs furloughed at the end of February 2021, there is scope for a significant increase in unemployment when the furlough scheme ends unless the economy rebounds strongly and with it demand for workers.

- The economy of the North East has seen twice the fall in payroll employment as Scotland as a whole, while the Oil and Gas sector might bounce back as the global economy rebounds, there is an urgent need for support for the region if it is to avoid long-term economic damage.

- The latest data suggest that we’re already seeing a significant increase in unemployment amongst those aged 16-24. Research suggests that even relatively short periods out of the labour market can have longer-term ‘scarring’ effects on young people. It’s going to be key to support young people to engage in education and training in order to aid them in seeking employment. Failure to get this right will have profound longer-term consequences.

Medium-term

- Learning the lessons of the post-financial crisis period, we are likely to see a greater emphasis on trying to avoid growth in fragile work through the economic recovery. While the formal legislative powers to do so are reserved to the UK Parliament, the Scottish Government has a number of options available to it to progress this issue (and indeed has already done so in recent years).

- With the devolution of income tax powers, the Scottish Parliament has the ability to influence labour market conditions in Scotland in a new way. And it has chosen to do so, raising tax on higher earners and lowering it on lower earners. Half of workers in Scotland now pay less income tax than if they were in the rest of the UK, although at most this reduction in tax amounts to £20 a year. Meanwhile, workers earning above £27,000 pay increasingly more tax. For example, someone earning £50,000 in Scotland now pays around £1500 more a year in tax than they would if they lived in the rest of the UK.

Through the forthcoming Parliament, as tax records become available for research, we should begin to learn about how this increasing gap between the tax paid in Scotland and the rest of the UK affects individual and business behaviour. It is unlikely that anyone would change their behaviour in response to £20 a year less in tax, but more likely that the increasingly higher taxes levied on those on higher incomes will begin to shape individual and business decisions.

Longer-term

- A key challenge has been and remains skills gaps, in particular in our remote and rural communities. The reopening of tourism activity this summer will be a key test of how the UK’s exit from the EU has affected this situation – the general expectation is that it will have worsened it, but by how much we will soon learn. It’s going to be important through the next parliament that practical measures are brought forward to support our rural economies to attract skilled migrants into the community. While immigration powers are reserved to the UK Parliament, many of the wider practical barriers are in devolved areas of responsibility, most obviously in housing. It is important to understand why Scotland does not get a higher share of migrants to the UK.

- There are however, broader questions too about the focus of the education and skills system in Scotland and whether or not our current efforts are providing businesses – from large corporates through to small-scale social enterprises – with the pool of labour with the right skills for what they need. This opens up possibilities for discussions around the balance of graduates versus apprenticeships in the economy etc.

Conclusions

The Scottish economy and labour market will be shaped by the pandemic for some time to come. For all the pledges made during election campaigns, the difficult work of rebuilding the economy and supporting the labour market lies ahead.

As a small open economy, Scotland is likely to find itself shaped by, more than shaping, important trends in the economy and labour market. This would be true under any constitutional settlement. This makes it all the more important that the next Scottish Government is engaged with businesses across Scotland, working in partnership with them, working with Governments across the UK, and making the hard decisions necessary about where to put its investments to produce the biggest return.

Authors

Head of Research at the Fraser of Allander Institute