Economists aren’t known for their sense of humour. Economics statisticians less so.

So it was highly ironic – albeit perhaps not very funny – that just two days before the UK’s departure from the EU, analysts in the Scottish Government published their latest annual account of Scottish exports.

As expected, much of the reaction concentrated on the importance of the EU for Scottish trade.

But the statistics also contain interesting information about the pattern of trade from Scotland more generally.

In this blog, we take a look at a couple of these trends, and notably the importance of manufacturing.

The headline numbers for 2018

A quick recap.

Last week’s figures showed that international exports from Scotland rose by £1.1bn – or 3.4% – between 2017 and 2018 to £33.8bn. The improvement was driven by exports to the EU, which rose 4.5% to £16.2bn.

Scotland’s exports to the rest of the UK (rUK) were also up by 2.5%, to £51.2bn. rUK exports make up around 60% of Scotland’s total exports (more of that later).

We wrote last year about a missed Scottish Government target to increase international exports by 50% between 2010 and 2017. The target figure has still not been reached even one year on; international exports have only increased by 39% since 2010.

It would seem that this target has been quietly dropped – a further case of when the facts change, the government change their targets…

If anyone remains in any doubt about the risks of Brexit, these latest trade estimates provide a hefty reality check.

The figures confirm – once again – that nearly £1 in every £2 worth of international exports from Scotland in 2018 were destined for the EU.

Eight of Scotland’s top ten international export destinations are members of the Single Market.

Table 1: Export destinations by market share, 2018

| Rank | Destination |

Total Exports (£ m) | % of Total |

| 1 | USA | 5,520 | 16.3 |

| 2 | France | 2,990 | 8.8 |

| 3 | Netherlands | 2,840 | 8.4 |

| 4 | Germany | 2,485 | 7.3 |

| 5 | Belgium | 1,250 | 3.7 |

| 6 | Ireland | 1,235 | 3.6 |

| 7 | Norway | 1,165 | 3.4 |

| 8 | Spain | 975 | 2.9 |

| 9 | Italy | 880 | 2.6 |

| 10 | Brazil | 770 | 2.3 |

Source: Scottish Government

We export more to the EU bloc than we do to all of North America, the Middle East, Asia, Africa and Australasia combined.

A BRIEF ASIDE

Work with us

We regularly work with governments, businesses and the third sector, providing commissioned research and economic advisory services.

Find out more about our economic consultant services.

If anything, Scotland has become more integrated with the EU in recent years:

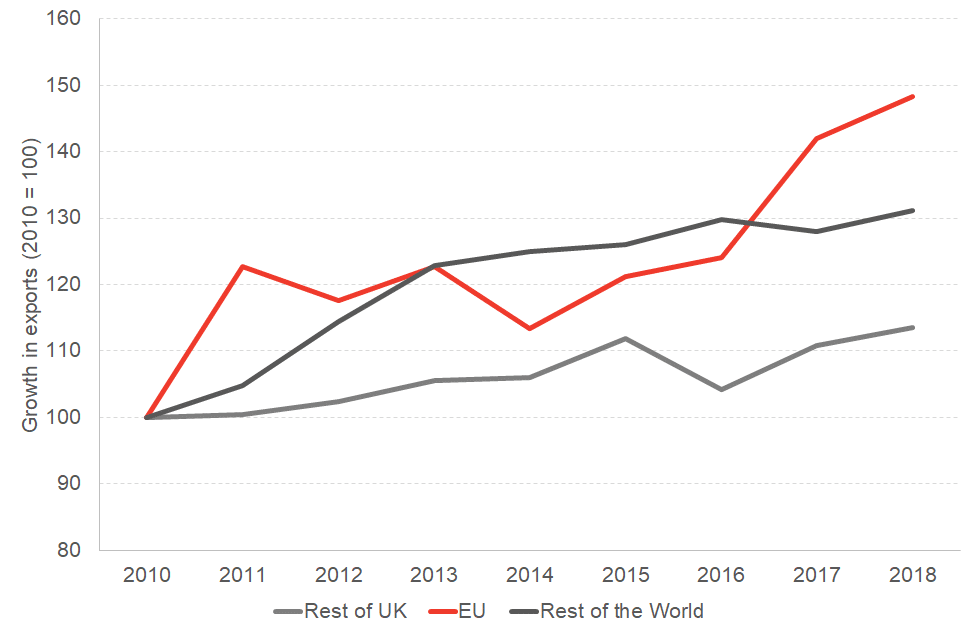

- EU exports grew by an average 4.1% per year over the last five years, compared to average growth of 1.3% in ROW exports and 1.6% in rUK exports;

- Since 2010, growth to the EU has outpaced growth to ROW and rUK by a significant margin – see Chart 1.

Chart 1: Performance of major Scottish export markets since 2010

Source: Scottish Government

It’s easy to see why many of our exporters are so troubled by the Chancellor’s recent comments that the UK will seek a limited trade deal with the EU at the end of the 12 month transition period.

Sadly it seems that UK policymaking is still driven by the politics of Brexit rather than what is good for our economy.

Of course, some will argue that a loose arrangement creates the opportunity for new trade deals beyond Europe.

True.

But there’s a simple reason that countries tend to trade with markets that are close to them…..and that’s because they are close to them.

A trade deal with Japan? Right on Boris! – double Scottish exports to Japan wouldn’t even match the growth in EU exports just last year alone.

A trade deal with Australia? Great idea Sajid! – but at less than £700m per year, it’s going to require a lot of Scottish produce to be shifted 10,000 miles to compensate for any hit to EU trade.

So what does Scotland export?

A further irony of last week’s statistics is that for all that we like to pride ourselves on being an international country, our economy isn’t.

Despite key strengths in some sectors – such as whisky and oil and gas – and amongst individual businesses, we have underperformed relative to our ambitions. Exports as a share of the Scottish economy have remained largely flat over the past 20 years, despite a sharp rise in globalisation.

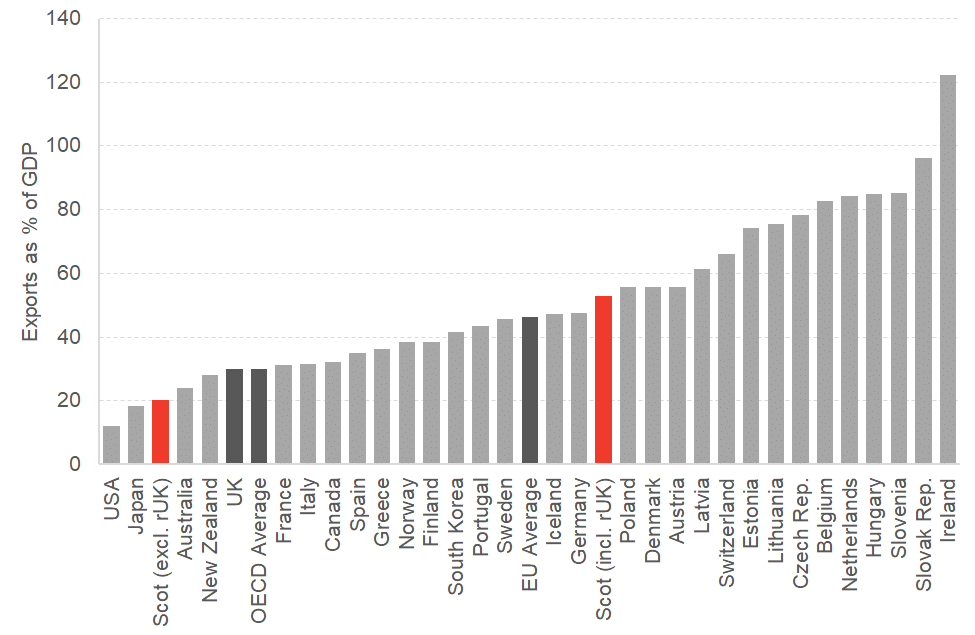

Today our international exports are equivalent to around 20% of Scottish GDP. For the UK as a whole, that figure is 30%. For Germany it is 47%.

Chart 2: Exports as a % of GDP in OECD countries, 2018 (Scotland excluding & including rUK exports)

Source: Scottish Government & OECD (FAI calculations)

Successive governments have tried to turn this around.

Over the years we have had various initiatives to tackle some of the perceived barriers to exporting or promote Scottish produce to a global market. Some have worked, some haven’t.

But a rather obvious – albeit often overlooked – fact is that to a great extent the very underlying nature of Scotland’s export performance is simply a reflection of the structure of today’s Scottish economy.

Scotland is a serviced based economy – indeed services make up 75% of day-to-day activity in the Scottish economy.

Unfortunately, many services are difficult to export.

You can’t trade a haircut over an international border.

And whilst barriers have been reduced in some services such as banking, different legal structures, regulations, tax systems and licensing requirements, often make it near impossible to trade overseas (even if in theory it is possible). How many of us have a mortgage from a US bank?

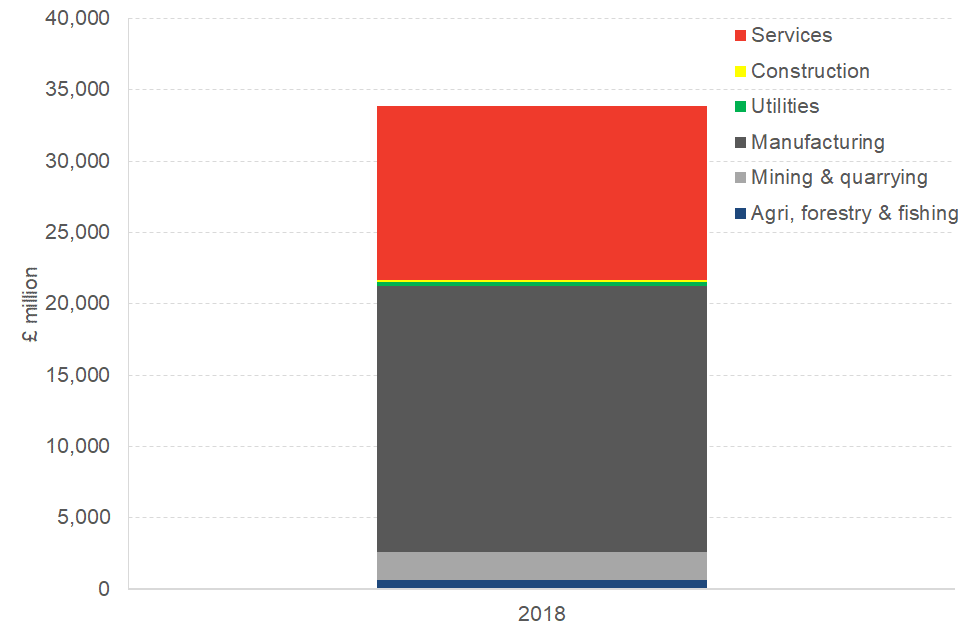

In contrast, most exports are made up of manufactured goods.

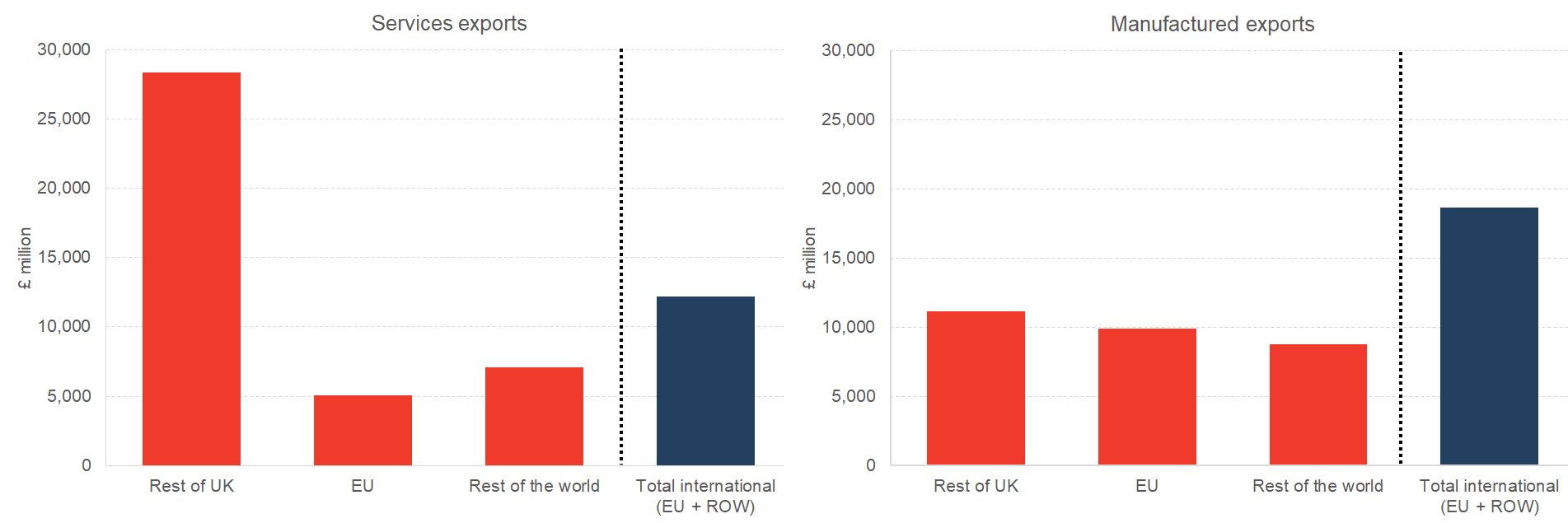

Despite manufacturing only making up 11% of our economy, we export 50% more manufactured goods than we do in services (£18.7bn vs. £12.2bn, see Chart 3).

[NB: Of course, it wasn’t always like this. When the Fraser of Allander compiled the first ever full set of economic accounts with the then Scottish Office (back in the mid-1970s), manufacturing was over 1/3 of the Scottish economy.]

Food and drink exports – at £6.3bn – computer, electrical, machinery & transport equipment exports – at a combined value of £4.7bn – and refined petroleum & chemical product exports – at £4.0bn – are all comfortably ahead of our largest services exports (professional services at £3.4bn and financial & insurance activities at £2.2bn). The same is true for the UK. In 2018, the UK exported £350bn worth of goods, compared to £307bn of services.

Chart 3: Composition of Scottish international exports, 2018

Source: Scottish Government

So any debate about Scotland’s export performance cannot be separated from a wider discussion about the underlying structure of our economy.

If we want to improve our export performance in the long-run, we can’t just talk about measures to make it easier and more attractive for Scottish businesses to export, but we need also to have a conversation about the ‘type’ of economy that we have in Scotland.

International vs. rUK trade

It is this underlying structure of the Scottish economy that also explains the relative importance of different markets for Scottish exports. Something that often gets lost in never-ending constitutional debates about the importance of the EU market vis-à-vis the UK and vice versa.

The trade data shows that as Scotland has evolved to become a service based economy, it has increasingly become ever more of a satellite regional economy of the UK.

To show this, it is possible to unpick exports both by origin and type.

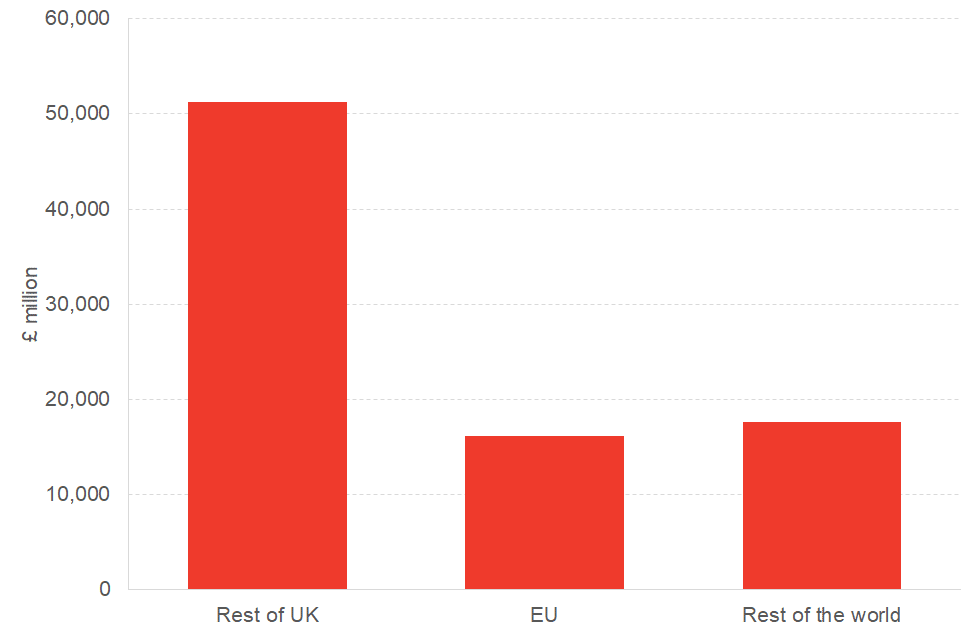

As we know, exports to the rest of the UK account for around 60% of total Scottish exports.

Chart 4: Scottish exports by market destination, 2018

Source: Scottish Government

But Scotland actually exports more manufactured products – i.e. things that are exportable over international borders – to countries outside the UK than it does to the rest of the UK – see Chart 5.

Chart 5: Scottish manufactured and services exports by market destination, 2018

Source: Scottish Government

But in contrast, for services, the UK is by far the dominant market.

And here lies the double-edged sword.

Success in developing a vibrant services sector over the years has brought a relatively high standard of living to Scotland, particularly compared to other parts of the UK outside of London. But it’s also created a relatively greater dependence upon the UK market for demand. By becoming less of a country that ‘makes things’ it follows that meeting our export ambitions becomes that bit harder.

Now some will see this as an argument for constitutional change, with independence providing an opportunity to follow the lead of other small independent European economies and to create a more vibrant and internationally facing economy.

Others will argue that none of this is guaranteed. And at the same time, they will point to the substantial risks to jobs and prosperity of attempting to unpick the integrated service sector links between Scotland and the rest of the UK highlighted in Chart 5.

Either way, what it does suggest, is that the Scottish Government – if they remain serious about setting out a convincing case for the economics of independence – are going to have to set out how existing patterns of trade, both internationally and the rest of the UK, will be impacted (both for better and for worse) through constitutional change. It won’t be sufficient just to make bold claims about what ‘is possible’.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.