One of the striking things about this crisis is that, in many ways, we have known it has been coming.

Pandemics have been a constant feature of global risk registers for a generation. Indeed, infectious diseases have featured regularly in the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Risks Report. The UK Government has also recognised the threat in each in every one of their own civil contingency risks.

But three things stand out.

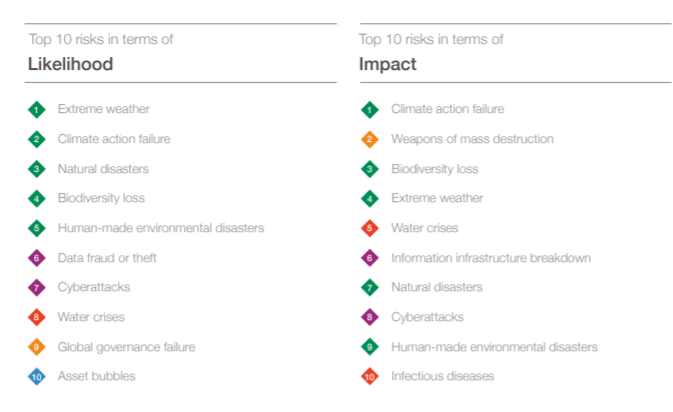

Firstly, whilst global health emergencies have been a constant feature of most risk registers for years, they haven’t really registered in the consciousness of most people in advanced economies. And if anything, post SARS and Ebola five years or so ago, they have slipped back (just creeping in to the Top 10 of Global Risks for Impact, but not Likelihood, in the most recent WEF risk report – see Table 1).

Table 1: The Global Risks Landscape 2020

Source: WEF Global Risks Report 2020

True, the UK Government’s latest risk register ranks pandemic influenza and the emergence of an infectious disease as relatively likely (3 on a 5-point scale of likelihood) and the impact of a pandemic as severe (5 out of 5 on a severity scale). But how much has this truly impacted upon wider society’s risk awareness and planning? (particularly compared to others such as terrorism, cyber-security or climate change).

Secondly, it seems that our economy, both locally and globally has been completely unprepared for a pandemic of this nature. But again, we’ve known this. A recent comprehensive assessment of health security and related capabilities across 195 countries found fundamental weaknesses around the world. It concluded that no country is fully prepared to handle an epidemic or pandemic (although the UK did score 2nd highest).

Thirdly, for all the discussion of risk and the preparatory work that will no doubt have taken place, the speed in which the crisis escalated caught many off-guard. As an indication (and this is emphatically not to be critical of them as they were working with the information available) the Office for Budget Responsibility closed their Budget forecast in mid-February with the assumption that “the coronavirus looked likely to be contained largely within China and to imply only a modestly weaker outlook for world trade and UK export markets”. Just a month later, large parts of our economy were in lockdown.

Of course, as the risk registers show, there are many threats at any given time, all of which have to be considered simultaneously. But has our collective appreciation of the risks and fallout been as it should have? And were we complacent?

More generally, as a society we’ve not had much of a discussion about the links between global health and the economy (perhaps excluding SARS and Ebola) in the same way with other risks (e.g. climate change) – despite warnings, see here.

What are the economic implications from this?

Clearly many of the reflections on risk planning will concentrate upon the public health and wider societal response and resilience.

But there will also be important economic questions.

Firs, how resilient is our economy to risk? This pandemic is not just a crisis in its own right, but also an important signal of the potential impact of any major risk – from cyberattacks through to natural or human-made environmental disasters – and the fallout it can cause. Indeed, how resilient might we be if a two or more of these risks were to crystallise at any one time? Whilst many of us get used to home working, it doesn’t bear imagining the consequences of a major cyber-breakdown? And whilst we seem in some areas to be good at preparing for risk, in others we systematically fail (see flooding!)

Second, how prepared are we to respond to such risks when they emerge? Whilst policymakers have responded admirably, it is clear that much of this is being made-up as we go. Reflecting upon the lessons for the future, when the time is right, will be an important task. There are already, and will continue to be, many take-aways from how the government itself has reacted, as well as from the readiness and response of business. (Un)Fortunately, we don’t get practice rounds for crises, so it would seem crucial to learn as much as possible as it relates to as many risks a possible, not just those related to global health.

Third, to what extent has the economy we have built contributed or helped to mitigate the worst effects of the crisis? The growth of technology has clearly helped many of us. But what about the role of globalisation? The interdependency of economies, the openness of borders and international mobility has quickened the speed at which the virus has spread. It has also exposed the risks from relying upon long-reaching supply chains and the weakness of not being able to draw on business resources and expertise close at hand. It also poses questions about our core manufacturing capacity that we have ready to respond to urgent demand in key areas, whether that be ventilators through to plastic bottles for disinfectant and protective personal equipment.

However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that we should seek to reorient our economy – there are costs here particularly if we are less efficient at production than elsewhere. The alternative may be better preparedness and government stockpiling of critical inputs to deal with the situations on the risk register. Although also costly, the overall economic cost (including opportunity cost) may be lower. If the precise nature of crises are difficult to predict then both options are problematic, and spending time building structures for international co-operation in crises to allow flexibility to use global resources to respond looks preferable – although by no means doable.

Fourth, how do we price risk into our decision making. Might this experience change our attitude to ‘value’ across all aspects of business continuity, internationalisation and procurement? For years, our model has been built upon a lowest price solution, with less regard for any risk-adjusted approach. Might we not just care about how cheaply we buy something, but also how accessible it is should the worst happen?

Fifth, it is clear that the ability to cope with these risks playing out – both at an individual level and at a business/sector level – differ greatly across the population. As always, it is the vulnerable that are most exposed. Ten years on from the financial crisis and a decade of austerity, many families struggling to make ends-meet face renewed uncertainty and economic hardship. There will likely be questions raised as how to appropriately protect the most exposed against these risks, and indeed choices to be made on where the burden is placed in any future state retrenchment.

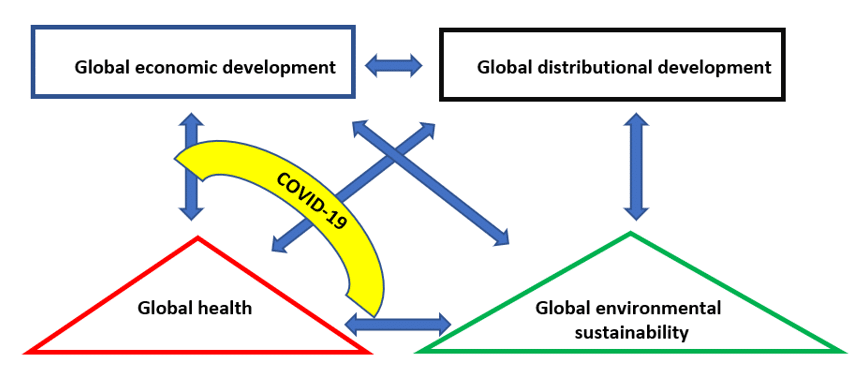

Sixth, to what extent do we fully understand and appreciate the link between our economy, the wider socio and environmental landscape in which it operates, and the interconnected risks? The current crisis has made clear the link between global public health and economic health. But might it be a wake-up call on the links between environmental health and economic health too?

It is often easy to forget, but our economy and society are inextricably linked to both our environment and health. This crisis links the economy with health. But if this crisis teaches us one thing it could be that seeing global health and global environmental sustainability as the underpinning and precondition for our global economy, irrespective of the precise political and societal choices, is crucial.

Finally, there will be big questions about who bears the cost of responding to the risks once they emerge. The government has – quite rightly – provided massive financial firepower. But had we even considered an eventuality in the 21st century a situation of our national governments as the economy of last resort? In time, this will have to be paid for. But who by?

Economic Policy in the face of risk

There is no doubt that enacting economic policy both during and in preparation for a crisis is extremely difficult. The level of uncertainty as to the length of the current pandemic and its implications for the economy are stark evidence of this. It is also evidence that the approach to policymaking should be broad, reflective and collaborative.

When the time is right, it seems important to “sit down” as a society to reflect upon our preparedness for such shocks and the effectiveness of our ability to respond. This shouldn’t be to tear down or criticise the efforts made during these unprecedented times, but rather to build on them for future and translate them into preparations for other crises where possible.

In such discussions there might too be some tricky debates about the role of government and society in insuring against future risks.

But this can’t take place in Scotland or the UK alone. The interdependence of regional and world economies means the risk posed by future threats are shared. It can be argued that we should also share in preparation, working with others to shore up responses to risk in everything from travel to supply chain management.

Finally, policymakers will have to remain flexible. There is no way to insure fully against any future crisis that might occur. Another stark lesson from the current crisis is the level of uncertainty surrounding its nature even in its midst.

These are difficult tasks that will inevitably require a great deal of resource, both financially and intellectually. They are also broad and wide-ranging. Given our experience of the Covid-19 pandemic so far, however, they seem like a reasonable place to start when thinking about protecting (as much as possible) our society and economy from future risk.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.