The CoVid-19 pandemic has awoken many to the role that key workers play in our society. But who exactly are they, and what do we know about them? This short article provides a summary of analysis carried out using pre-crisis Labour Force Survey data to help give us a basic understanding of this group of workers.

In Scotland, the Scottish Government has left it to Councils to designate key workers. Although there may be some small differences, we expect that the designations will be largely similar to the definitions we have adopted for this analysis.

1. Over a third of workers in Scotland are a key worker

More precisely, 34% of workers in Scotland come under the definition of key workers, a similar proportion to that of the whole UK. This equates to approximately 920,000 people in Scotland.

2. Key workers come from a diverse range of sectors

We have used the same definition for our analysis as the Office for National Statistics. They have identified the industry and occupation groups that correspond best (although not quite exactly) with the UK Government’s definition of key workers.

These cover a wide variety of professions from butchers and bakers (although unfortunately not candlestick makers) through to health professionals, social workers, broadcasters, police and transport and utility workers. More detail can be found here. Broadly they fit in the following categories:

Table 1: Key workers in Scotland by category

| Key worker category | Number of workers | % of total key workers |

| Health & social care | 320,000 | 35% |

| Education & childcare | 160,000 | 17% |

| Food & necessary goods | 140,000 | 15% |

| Utilities and communication | 140,000 | 15% |

| Public safety & national security | 60,000 | 6% |

| Transport | 60,000 | 6% |

| Public services | 40,000 | 4% |

| National & Local Government | 20,000 | 2% |

Source: Q4 2019 Labour Force Survey

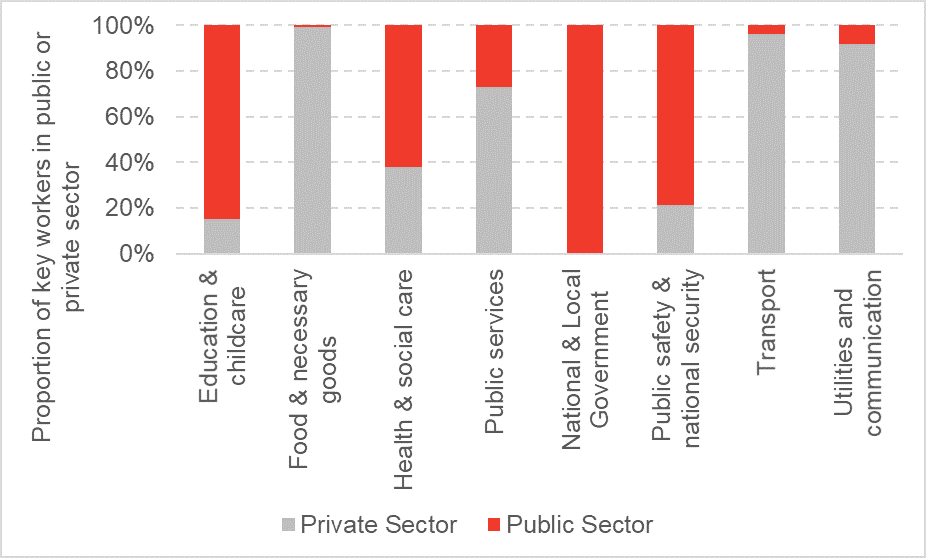

3. Nearly half of key workers are in the public sector

Just over 40,000 key workers in Scotland are employed by the public sector. This differs by key worker category, and it accounts for the majority of key workers in education and childcare, public safety and national security and (obviously) all of national and local government. Over 60% of health and social care key workers are public sector employees.

Chart 1: Proportion of key workers in public and private sector

Source: Q4 2019 Labour Force Survey

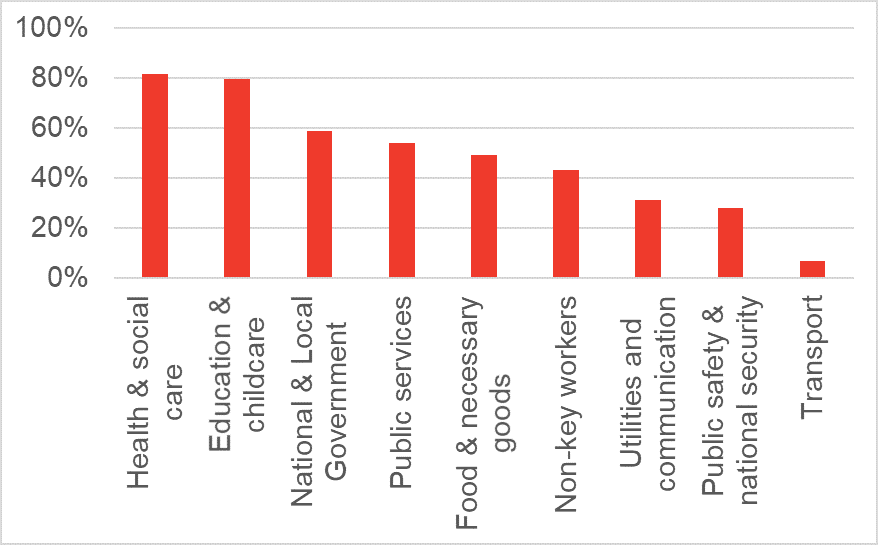

4. Most key workers are women

It’s a 60:30 split in favour of women workers to men in Scotland, again similar to the UK as a whole. Women are most represented in health and social care (82% of the workforce are women) education and childcare (80% ) and least in Transport (7%).

Chart 2: Percentage of key workers who are women

Source: Q4 2019 Labour Force Survey

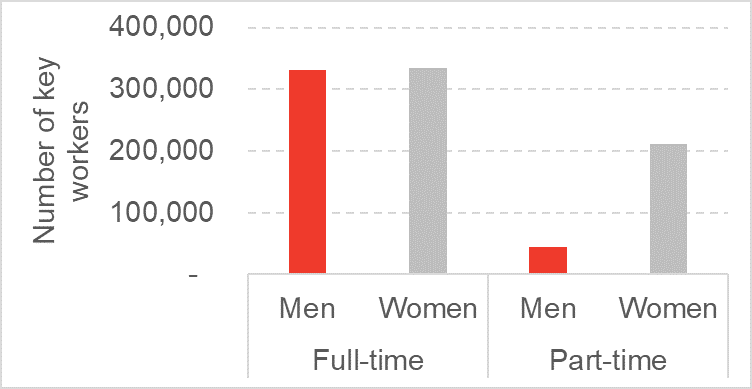

5. Around a third of key workers work part-time, and most of those are women

For those that work full-time (around 2/3 of all key workers) these are evenly split between men and women.

There are around 250,000 part-time workers, and 80% of these part time workers are women, a common theme across the whole labour market with women more likely to take part-time hours to balance work and childcare.

Chart 3: Number of key workers who work full-time and part-time, by gender

Source: Q4 2019 Labour Force Survey

The sector with the most part-time work is health and social-care (110,000) followed by education (45,000). 90% of part-time work in these sectors is done by women.

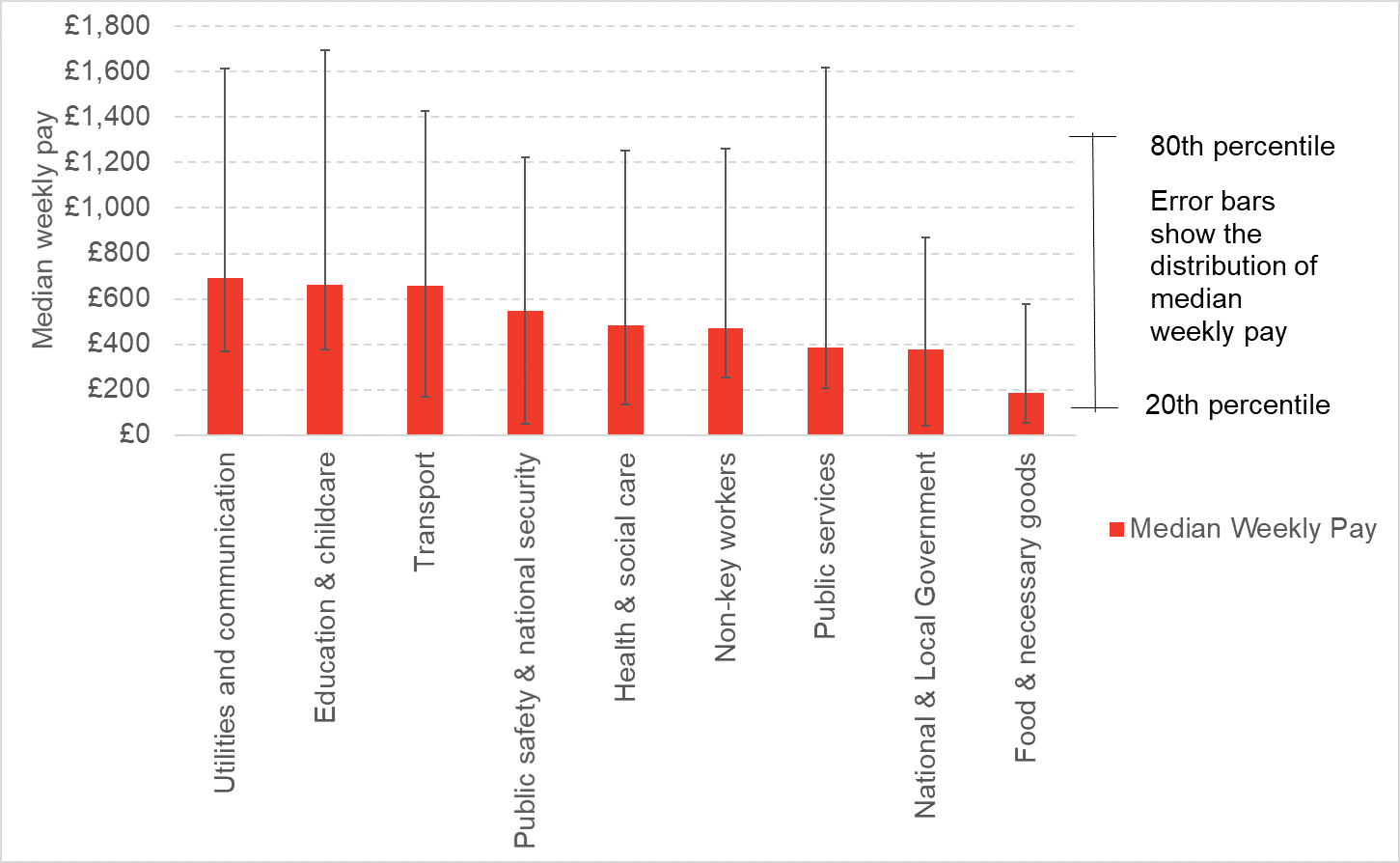

6. Those working in food and necessary goods have the lowest pay and hours

Average median weekly pay in Q4 2019, according to the LFS, was £480. This is close to the (more reliable) estimate of £470 for 2019 as recorded in the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE).

Weekly pay is determined by a combination of hourly pay and hours worked.

Three key sector categories, public services, national and local government and food and necessary goods have lower weekly pay than this. Within public services, there is a wide variation in weekly earnings, including as it does broadcasters and judges through to charity workers. Although less wide than in public services, most sectors have very wide variations in weekly pay.

Chart 4: Key workers in Scotland by category: hourly pay and hours worked

Source: Q4 2019 Labour Force Survey

Those in the food and necessary goods category (broadly covering food processing, delivery and sale) received the lowest hourly pay and work the fewest hours giving them the lowest estimate of median weekly pay. The narrow variance in pay between the 20th and 80th percentile reflects that this is a predominantly low pay sector.

7. Even within Scotland, the number of key workers in each region differs

The ONS have produced a map showing regional differences:

Figure 1: Proportion of key workers in workforce by Local Authority

Source: ONS

East Renfrewshire has the highest proportion of key workers amongst its workforce at 44.6%. Aberdeen City has the lowest at 28.1%.

This is all very interesting, but what does it tell us?

As many have noted, this crisis has highlighted that society would struggle to function without those who were designated as key workers. There have been questions asked about whether our economy values these workers appropriately – or in other words, whether or not they get paid enough.

The fact that a third of the workforce in Scotland falls under this key worker designation shows clearly that they are a significant group of people in our labour market. Whilst, on average, it appears many key workers are paid above average this disguises a lot of variation. In food and related services there is no disguising – this a low paid sector through and through.

Increasing pay for key workers is not necessarily straightforward. There are numerous factors which determine pay levels that rarely take into account public opinion, and it also presents difficult questions. For example, if we want those in food and necessary services to be paid more, are we prepared to pay more for our food? Is a sector by sector minimum wage where we want to go? Or are we seeking a shakeup of the industry so that profit (and loss?) is shared more equally?

The fact that nearly half of key workers are in the public sector at least gives a more direct route for governments to ensure that designated key workers are remunerated appropriately – but perhaps no easier answer as to how to raise additional money to do that, or indeed a consensus on what an appropriate wage would be.

Nevertheless, the focus on key workers could be a helpful focus for government efforts to push forward ‘fair-work’ practices. There appears to be widespread agreement that these workers should be especially well treated due to the importance of the work that they do. The existence of risk factors for poverty in this workforce, such as low pay and part-time women workers, mean that this would be a good focus to meet other aims such as reductions in child poverty.

The added benefit is that this would help ensure we are resilient for the next public health crisis that comes along. There will be a lot of key workers who will be reaching burn-out just now, but if this crisis shows anything it’s that we need them to keep on doing what they are doing and ideally more to join them.

Authors

Emma Congreve is Principal Knowledge Exchange Fellow and Deputy Director at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Emma's work at the Institute is focussed on policy analysis, covering a wide range of areas of social and economic policy. Emma is an experienced economist and has previously held roles as a senior economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and as an economic adviser within the Scottish Government.

Mark Mitchell

Mark Mitchell is a former research associate at the FAI. In 2021, Mark moved to a post in the Competition and Markets Authority. His research area is applied labour economics, focussing on the causes and effects of human capital accumulation over the lifecourse.