Scott J. McGrane, Grant Allan and Graeme Roy

The prolonged period of warm and dry weather during June and early July is at odds with what many of us would call a “traditional Scottish summer”. These conditions however, are representative of a number of quite extraordinary global weather events that have occurred in the past few months. From the ongoing drought conditions, wildfires and subsequent flooding and landslide events that ravaged California last year, the near-miss of “day zero” in Cape Town, where dry conditions and poor water management almost resulted in no water supply being available, and the global heatwave currently impacting many countries across the globe, climatic extremes have had significant impacts on livelihoods, infrastructure and economies alike.

In this note we set out whether this is genuinely atypical weather, what the consequences have been for water in Scotland (both in terms of supply and demand), before discussing what is currently known about the links between Scotland’s economy and water. We conclude with a discussion of what this recent period might mean for the Scottish economy in a future climate in which water characteristics seen over the last few weeks may be more regular occurrences.

This is part of a new project we’re working on with colleagues at Stanford University in the US looking at the role of technology in improving environmental measurement and the potential implications for our economy.

Some examples illustrate the global hot period seen recently: A major heatwave in Quebec has contributed to around 70 deaths during the summer, with thousands more being left without electricity as infrastructure overheats, while Japan has seen a rising death toll as a result of unprecedented heat. In Oman, the town of Quriyat recorded the record highest “low” temperature in a 24 hour period of 42.6°C, while parts of northern Siberia experienced temperatures around 32°C.

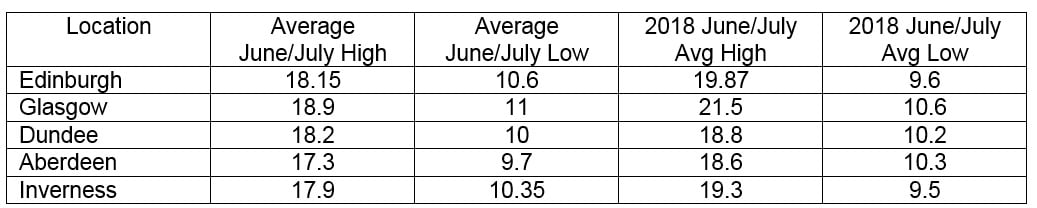

In North America, Los Angeles (43.3°C), Denver (40.6°C) and Montreal (36.6°C) have all witnessed their highest ever recorded temperatures. Even in Scotland, we have seen a prolonged period of high temperatures, much higher than the seasonal average (Table 1), though the record high temperature that was initially thought to have been set by a recording in Motherwell of 33.2°C has since been dismissed owing to contamination by a non-weather-related factor. As it stands, the official record temperature for Scotland remains 32.9°C, recorded at Greycrook (2003), while the UK record temperature remains at 38.5°C recorded at Faversham in Kent (2003).

Table 1: June/July average (1981-2010) and June/July 2018 average temperatures for select Scottish cities (all units in °C)

Has this summer been atypical in Scotland?

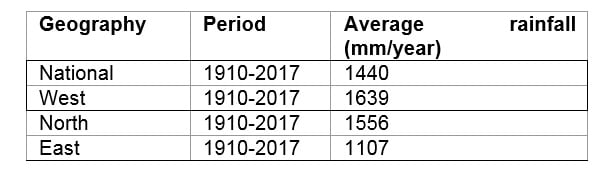

As we all know, Scotland is typically regarded as a wet country, with plentiful freshwater resources available to sustain the demands imposed by society, the economy and our diverse ecosystems. On average, Scotland receives around 1440mm (c.1.4 metres) of rain per annum, with a marked rainfall gradient from west to east. Typically, Glasgow receives around 1245mm of rain per annum, while Edinburgh receives 704mm per annum. As Scotland’s weather systems predominate from the Atlantic Ocean, they arrive on the steep elevations of the western coastline where they are forced upwards via a process called orographic uplift. As these systems gradually move from west to east, they deposit rainfall along the way, with volumes dissipating by the time they reach the low-lying eastern region of the country (Table 2).

Table 2: Average annual precipitation values (1910-2017) for Scottish Geographical Regions

Source: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/about/districts-map

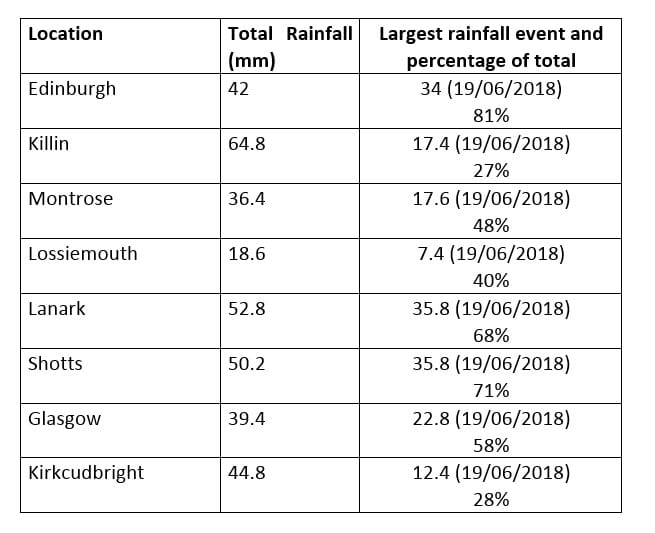

In addition to the elevated temperatures across Scotland, these summer months have seen a distinct lack of rainfall to July 20th. Observed rainfall since the 12th of June has been particularly low, with one storm system on the 19th of June providing the majority of measured volume during this period (Table 3).

Table 3: A sample of precipitation monitoring sites across Scotland, 12th June 2018 – 11th July, 2018

Source: http://apps.sepa.org.uk/rainfall

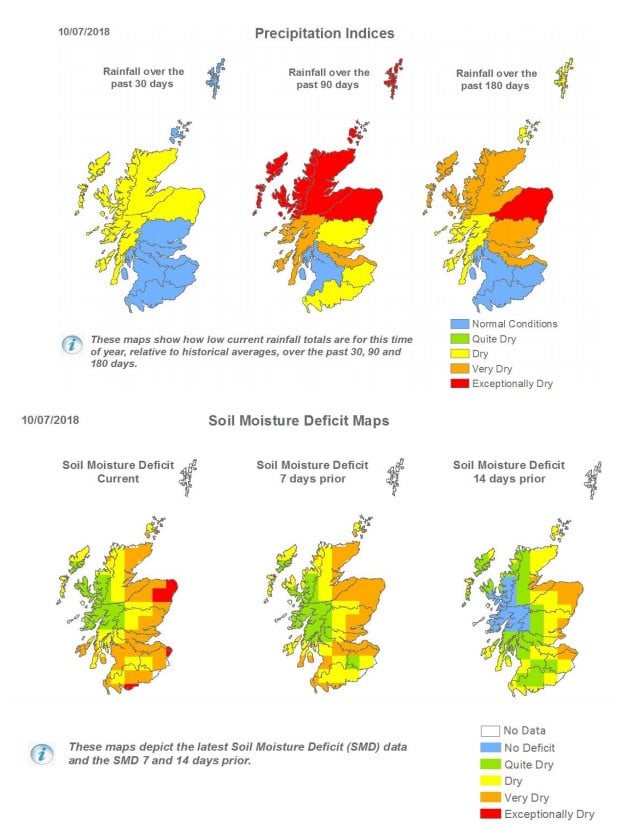

This has resulted in reduced soil moisture and river levels across the country (Figure 1).

What has this meant for water supply?

As a result, moderate levels of water scarcity – reported regularly by SEPA – are currently being observed in the northern Highlands, North Fife, Angus, West Galloway, Girvan, the southern Highlands and the Northeast, with many other areas being on alert in light of the continuing dry forecast. In Morayshire, Scottish Water advised residents on the 15th of June to be conservative with their water usage including taking shorter showers and only running washing machines with full loads. Water supplies (both domestic and non-domestic) are largely served from surface reservoirs that have their levels monitored year-round. Scarcity is a metric derived by SEPA to identify periods where supply consistency becomes threatened by prolonged periods of low rainfall or river flows. It combines observed measures of rainfall or river flow over a standard period of time, current measures of soil moisture deficit and anticipated rainfall in a 5 day forecast.

Figure 1: Precipitation indices and soil moisture deficit maps for Scotland in 2018.

What does demand for water in Scotland look like?

Publicly available data for domestic and non-domestic water demand in Scotland is very limited. Coarse data published by the Scottish Government provide breakdowns for domestic and non-domestic consumption, leakage and operational use from 2010 to 2017. Across that period, 41% of water is provided for domestic consumption, while only 23% of water is used for non-domestic purposes. Approximately 33% of water is lost to leakage, though it is unclear from the data whether this is measured or estimated, something that has been observed to be increasingly problematic across all areas of the United Kingdom.

This dry period coincides with increasing demand for water supply across Scotland. The elevated temperature result in increased domestic consumption for hydration, leisure and gardening purposes. Additionally, tourism sectors in Scotland are reaching peak levels at the end of the Q2 into Q3, and as a result, water demand is artificially heightened from both increased direct (drinking, showers etc) and indirect (hotel operations, food preparation etc) demand.

While small changes in behaviour at the domestic level can help reduce water wastage during periods of dry weather, the implications for non-domestic customers may be a little more challenging. This is due to 1) water’s role as a critical input in specific economic activities, 2) the intensity of water usage varies between economic sectors, and 3) that changing the way in which water is used across industry will prove challenging in the short-term as firms are reliant upon existing technologies and water-intensive processes in their current operations.

Energy and agriculture water use make Scotland unusual

Globally, agriculture and energy production are the two largest end-users of water resources, accounting for 70% and 14% of total global water withdrawals respectively. However, in Scotland, the reliability of rainfall as a source of irrigation means that mains water used in the agricultural sector is primarily for washing equipment and provision of drinking water for animals. Soil moisture is maintained by regular precipitation, and spray irrigation is rarely used on Scottish fields. Contrastingly, in spite of their frequent water scarcity and drought conditions, California applies approximately 80% of its available water to irrigation of agriculture.

Energy manufacture in Scotland has rapidly moved away from fossil fuel generation (water intensive, through their need for cooling, conversion to steam) towards renewable sources, where wind, hydro, and biomass combine to provide 68% of Scotland’s electricity demand. This is likely to mean that Scotland’s recent success in moving towards a decarbonised electricity mix has positive advantages in terms of reducing water demand from this activity. These features of the agriculture and electricity industry in Scotland therefore mean that water usage within the Scottish economy is somewhat atypical when compared to other similar-sized, developed nations.

Predominate water users are in the refined petroleum and pharmaceutical manufacturing sectors, accounting for approximately 16% of all non-domestic consumption. Accommodation and food services, and food, beverage and tobacco manufacturing both use 10% of Scotland’s water supply, while both agriculture and electricity and gas supply only account for 8% and 7% respectively. In addition to piped water supply, direct abstraction from surface and subsurface resources are a critical component of economic activity for particular sectors. For example, in the Scottish whisky industry – with more than 1.2 billion bottles being worth in excess of £4.9 billion to the Scottish economy in terms of GVA – most distilleries extract product water directly from nearby freshwater resources, with piped supplies of water limited to use in the operational processes associated with cleaning, and maintenance of production and visitor sites.

In addition to direct usage of water, accounting approaches to water consumption are increasingly considering the water footprints associated with imports and exports, particularly water embedded in products that are grown or manufactured in water-stressed geographies. Many of the items that comprise the Consumer Price Index basket for the UK rely on extensive imports from countries that receive much less rainfall, resulting in a high water footprint associated with their production. For example, non-seasonal produce such as fruits, vegetables, coffees and wines are staples in the average UK shopping basket, but cannot be produced domestically owing to the climatic conditions. As a result, we rely on trade from countries that may already be experiencing water stress.

What might the recent dry spell mean for Scottish economy?

We will learn more about the consequence of the recent dry spell once aggregate measures of economic and environmental data become available later this year.

As we pointed out in our blog on the bad weather experienced in March, at an aggregate level, our economy is typically relatively resilient to changes in the weather. What is much more likely are changes within and between sectors.

For example, on anecdotal evidence there is pressure on growing conditions for many agricultural activities pointing to consequences for first crop harvest and pressures on animal feed with the lack of grass. Concomitantly, many parts of Scotland are enjoying higher visitor numbers from increased day trips and the peak tourism season, which brings an increased water demand across several sectors of the Scottish economy.

But what is much more interesting is how changes in the weather over a sustained period of time might impact on our economy.

As a public body responsible for the provision of freshwater supplies to domestic and non-domestic customers, Scottish Water are charged with ensuring continuity in supply and futureproofing their role as the primary water supplier in a changing world. Consequently, Scottish Water identify the following six elements as important drivers for change in the water landscape in Scotland:

- Climate change

- Demographic change

- Legislation changes

- Resource availability

- Political, Economic and regulatory environment changes

- Scientific and technological advances

In addition to the above, other elements will impact on Scotland’s future water demand. First, changes in economic structure – the move away from service sectors towards less water-intensive economic activities will likely lower non-domestic water demand. Second, changes in water intensity of economic activity within sectors with new technology – such as that seen in the recent changes in electricity production – have the potential to transform water demand. Third, domestic consumers and the efficiency of old and new properties in conserving water use. Further, as other regions start from less robust positions as Scotland, there may be opportunities for Scotland in comparative advantage of water intensive products.

All this points to a need to better understand links between environment, including water use and the economy, particularly as extreme climatic events such as the recent winter snowfall and subsequently dry summer period become more frequent. To thrive in a future Scottish climate, all parts of the economy will need to adapt accordingly to mitigate against resource depletion or reduced productivity.

Given the continued threat to freshwater resources from forces of environmental change (climate change and population growth), it remains to be seen whether the recent spell is a harbinger of future conditions. If so, it may provide an opportunity to understand and better prepare for an increasingly water-scarce future. The link between water availability/use and economic measures at aggregate and sectoral levels, now and in the future, provide the basis for our ongoing programme of work with partners at Stanford University. We will return to the effect of the recent spell of warm and dry weather on the Scottish economy later in the year, after more data are released.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.