Three years ago, we launched this blog shortly after the EU referendum.

Since then, we’ve tracked the performance of the Scottish economy through a period of unprecedented uncertainty.

Back in 2016, virtually no one – apart from a small number on the fringes of the debate – was even prepared to consider the prospects the UK leaving the EU without a deal. A smooth exit, a new relationship with the EU and the prospect of new trade deals was supposedly going to be straightforward.

Jump forward to today and the prospects of a ‘no deal’ outcome remains a distinct possibility. The hard-work on agreeing any future trade deal has yet to even start.

Meanwhile, through all this time, the UK’s reputation for effective governance and good policymaking has been thrown out the window. Businesses have had to operate in a world of uncertainty and rising costs, leading to delayed investment and the diversion of hundreds of millions of pounds (if not more) from productive activities to planning and preparing for the worst case scenario.

If a ‘no-deal’ was to come to pass, what could be the impact on the Scottish Economy? And how well prepared might the Scottish economy be?

What would the impact be of no deal?

One of the challenges in trying to predict the potential impact of a ‘no deal’ outcome is that there is little precedent to fall back on. There are few – if any – examples of a modern economy dislocating key markets and supply chains overnight.

Of course, the impact will vary significantly by individual firm and by sector depending, in part, upon how integrated they are into international supply chains. But all firms are likely to be impacted in some way, particularly if it leads to a wider shock across the overall economy.

As always, what is important is not whether or not a technical recession was to occur (i.e. two consecutive quarters of negative growth), but the sustained impact upon output and jobs. It is entirely possible to have a short sharp recession and to recover quickly. This is much less damaging than having a sustained period of weak, albeit positive, growth.

In a letter published on Tuesday, the Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney updated his scenarios of the immediate impacts of a no-deal Brexit.

Once again he emphasised that these are scenarios to “stress test” the financial system, and so should be seen as worst-case scenarios. Crucially they again assume limited policy response, and a whole host of different factors – for example, customs delays – being at the high-end of the scale.

The Bank now estimates that the worst-case scenario could lead to a peak-to-trough contraction of 5.5% of GDP, with unemployment rising to 7%. This compares to the Bank’s initial analysis – from last November – which pointed to an 8% contraction and unemployment rising to 7.5%. The key reason for this ‘improvement’ is due to the belief in the Bank that many businesses have taken steps to boost their resilience to any immediate dislocation in their markets.

But such a ‘shock’ would still be significant. To put it in context, this is around the same as the contraction seen during the 2008 financial crisis.

What would this mean for Scotland? A hit to GDP of this magnitude would equate to GDP being £9 billion lower. Unemployment would rise to nearly double the current rate, increasing the number of unemployed by 94,000.

Of course, the economy would bounce back at some subsequent point and some – but perhaps not all – of this lost economic potential might be recovered as the economy adjusted to the new ‘normal’.

The Bank of England also set out a number of other more positive scenarios, including that of a close “Economic Partnership”, which could see GDP grow by between 0.75% less or 1.75% more than their baseline forecast over the next 5 years.

They also highlight scenarios covering an outcome where there is a transition period (but limited ‘deal’), which they still estimate could have a negative impact of between 2.5% and 5.5% over a five-year period.

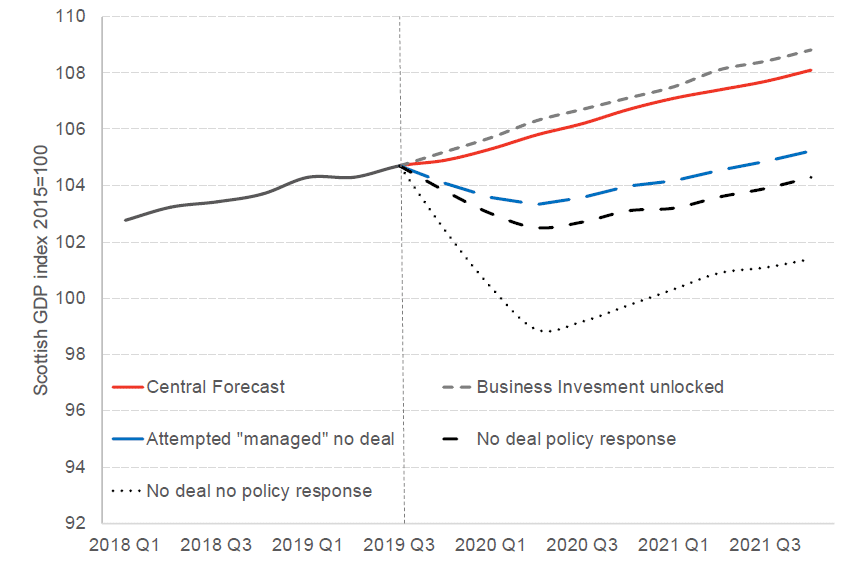

In our own work – published in our Economic Commentary in June – we looked at the potential immediate effects of different Brexit outcomes on Scotland (see chart). Here we set scenarios for how the economy may change depending upon a range of outcomes for exports, investment, and household spending.

Chart: FAI Central Forecast and Scenarios

Source: FAI

As an illustration, we showed three types of outcomes, each associated with different magnitudes of peak-to-trough contractions, based upon different levels of policy response and goodwill between the UK and the EU (even without a ‘deal’).

Even then, whilst we can be pretty confident about the direction of any impact, any modelling of the precise effects and associated point-estimates are associated with a high degree of uncertainty.

Of course, this analysis focusses upon the short-term. In the long-run, the economy will adjust and growth will return. Recent research by the ‘UK in a Changing Europe’ estimates that a “WTO Brexit” (that is, leaving without a Withdrawal Agreement) would lead GDP per head being between 3.5% and 8.7% lower after 10 years than otherwise would be the case. But it is important to remember two things:

- They look at the size of the economy compared to where it would have otherwise have been, i.e. compared to the status quo – growth will stake place but it will just be slower than otherwise would have been the case;

- These are scenarios rather than forecasts, and the ranges show the uncertainty attached to such estimates. The full range will depend greatly on the future direction of policy on both domestic and international issues.

Last week, we published new analysis of the potential impact on the Northern Ireland economy.

So how prepared is the Scottish economy for a ‘no deal’ outcome?

Most recent data for the UK showed a contraction in the economy during Q2 after a strong Q1 – driven, in part, by the unwinding of stockpiling that had taken place in the run-up to the first Brexit deadline in March.

Data for Scottish GDP in Q2 will be published later this month. We expect to see a similar pattern to that of the UK. Q1 growth was above trend at +0.6% but it seems likely that Q2 data will be weak – or perhaps even show a slight contraction. [NB: See our recent blog on our nowcasts for different parts of the UK.]

Over the longer-term, the Scottish economy remains in a low growth environment. The size of the economy in 2018 is only 3% larger than in 2008 (on a per head basis); a fraction of our long-term growth rate. Whilst there is record high employment, productivity growth over the last decade remains sluggish. Exports have been picking up, but costs are rising and business investment has remained low and stagnant.

All of this comes at a time when there are signs that the global economy may be losing momentum, further adding to the risks.

Business confidence remains fragile. Our Scottish Business Monitor has consistently shown a weakening outlook for investment, with Brexit cited as the key drag on capital spending. The Scottish Government’s measure of consumer sentiment remains negative.

So the resilience of the economy could be tested.

Final thoughts

There are huge uncertainties about the ultimate Brexit outcome. The range of scenarios that have been produced, for both the short term and long term, demonstrate this.

It is positive that there is some evidence that businesses are better prepared than they were, although like everyone else they remain unclear about the final destination for the UK’s relationship with the EU.

Any major upheaval in our economy – whether positive or negative – requires effective policy making and political leadership. The last three years suggests that we have been lacking in both.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.