Economic news are really kicking into gear after a quiet few weeks, with news of the latest vote on Bank Rate and the Bank of England’s forecasts, as well as the forthcoming arrival of the annual GERS publication. Let’s take these in turn.

Bank Rate cut, but only after a second vote

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee is a vote-first body – something we have got accustomed to, but which isn’t always the case in central banking. For example, the Federal Reserve – the US central bank – places a much higher emphasis on consensus.

Nonetheless, the MPC’s votes rarely end up in a deadlock. The only other occasion since BoE independence that has happened was in March 1998, at a time when one of the nine seats on the MPC was vacant. At the time, Governor Mervyn King’s casting vote was the decider.

This time, the split was caused by one of the MPC members, Alan M. Taylor, arguing for a more aggressive cut of 0.5 percentage points. When faced with a second vote between a 0.25ppt cut or holding rates, Professor Taylor sided with the more broadly supported cut.

Embedded inflation may be more permanent than hoped

Still, a 5-4 decision is far from a consensus view, and shows just how uncertain the outlook is.

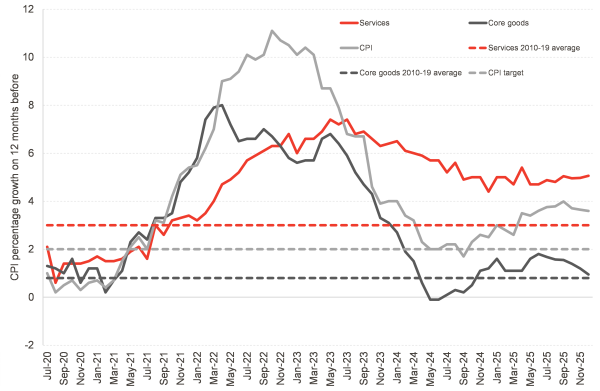

The Bank’s accompanying Monetary Policy Report revised short-term inflation prospects up, with September’s CPI reading forecast to hit 4%. This is of course much lower than the 11% peak in 2022, but it also reveals how stubborn services inflation has become.

Chart: CPI, core goods and services inflation since July 2020

Source: Bank of England, ONS, FAI analysis

The chart above clearly shows the more slow-moving but more persistent pattern of services inflation as opposed to core goods (that is, excluding fuel and energy) inflation. And while core goods inflation is now projected to soon be back at the 2010-19 average, which was consistent with the 2% overall target, services inflation appears to be accelerating again.

Wage growth continues to be high, which is driving up the cost base for services. Inflation is expected to average 3.5% across 2025; if we assume the Bank’s already relatively optimistic 0.4% underlying productivity growth, we should expect wage growth to be 3.9% this year. Instead, it has been running at between 5% and 5.8% this calendar year, and even if it tails off to the 3.75% to 4% in December projected by the BoE, the annual average will be significantly higher than inflation plus productivity growth.

That’s obviously good news for the real wages of those in receipt of them. But it also means several things that are less rosy in macroeconomic terms. The cost base for services relies much more on labour inputs than that of goods, therefore driving in large part the path for accelerating inflation – especially when combined with the increase in labour costs from the employer NICs measures that came into effect in April.

The high wage growth and stubbornly high inflation would also indicate that there isn’t much spare capacity. The UK economy is therefore running close to its potential – which is a worrying sign given how subdued economic growth has been. The Bank will hope that cutting rates helps stimulate activity, but if there is no spare capacity, then there is little monetary easing can do on the real side of the economy.

GERS day is nearly upon us

It’s time to rejoice if you’re a fan of official statistics, but also to brace yourself if you’re allergic to the copious amounts of tin foil hat nonsense around it that have come to be as synonymous with August as the Edinburgh Fringe.

If you’re hoping to avoid some of the latter, we have a handy guide to GERS, going into detail on the production of these statistics and their publication, and addressing some of the myths and odd theories around them. We also did a podcast episode back in 2020 focused on these. We’ll be doing a podcast next week, on publication day, to talk through the new data that will be published.

But to go through the main claims usually made about it:

- GERS is an accredited National Statistics produced by statisticians in the Scottish Government (so is not produced by the UK Government) and is a serious attempt to understand the key fiscal facts under the current constitutional arrangements.

- Some people look to discredit the veracity of GERS because it relies – in part – on estimation. Estimation is a part of all economic statistics and is not a reason to dismiss the figures as “made up”.

- Will the numbers change if you make different reasonable assumptions about the bits of GERS that are estimated? In short, not to any great extent.

- If you have any more questions about how revenues and spending are compiled in GERS, the SG publish a very helpful FAQs page, including dealing with issues around company headquarters and the whisky industry (which can often be the source of misinformation about GERS).

What will the numbers show?

It’s hard to know for sure – but it would not be surprising if the numbers ended up fairly close to last year’s. The UK’s overall deficit was 5.1% of GDP in 2024-25, an increase from the 4.8% recorded in 2023-24. This was driven mostly by falls in receipts as a share of GDP, which were only 39.3% of GDP (40.0% in 2023-24).

This is mostly due to the National Insurance Contributions cuts in Jeremy Hunt last fiscal statement as Chancellor, although there were also some additional falls in receipts. Specifically of interest to the GERS numbers is the £0.9 billion fall in North Sea revenues, or 0.04% of GDP. This would suggest a small worsening of Scotland’s net fiscal balance.

There are of course lots of moveable parts which make it difficult to predict exactly what the figure will be. However, Scotland’s net fiscal balance will still be negative and larger than the UK as a whole as a share of GDP.

So what does all this mean? Why does it matter?

The significance of GERS depends somewhat on your view on the constitutional question, but the cut and thrust of debate around these statistics leads to some curious statements if one thinks about it for a wee while (and we think about it a lot!).

To emphasise, GERS is not a description of the Scottish economy, does not describe the success or otherwise of the economy. The overall growth in the economy is measured through the GDP statistics, health of the labour market through labour market statistics, changes in living standards through changes in statistics like disposable household income.

GERS measures tax and spending, and the difference between them: certainly, related to the health of the economy (e.g. if economy is growing, and wages are growing strongly we will probably be getting more income tax), and the bigger the economy is the smaller the deficit will be (given it is the denominator in the calculation), but these statistics are not a “verdict” on the Scottish economy.

The generally higher deficit in Scotland (particularly if we exclude volatile oil and gas revenue) mostly comes down to much higher spending on services per person. This has been the case over the time series of GERS (which starts in 1998-99).

This in turn is because of the way the Scottish Block Grant is calculated using the Barnett formula, which baked in higher spending per person when it was introduced in 1979. Changes through the fiscal framework since 2016 have made some changes to the overall funding made available to the Scottish Government due to income tax devolution and the devolution of some other taxes and benefits, but the Barnett formula is still the key reason for higher spending in Scotland.

So, we would interrogate the statements politicians make about GERS through the lens of their view on the level of spending in Scotland.

Some people might say, as they have in the past (even though they are generally supporters of the union) that GERS shows “SNP mismanagement of the Scottish economy”. This doesn’t really make sense, as what it broadly shows is the higher public spending due to the Barnett formula which supporters of the Union would presumably point to as a benefit of the Union (of course some do, just to be clear).

In turn, we saw the curious double-think during some of the years of austerity where the Scottish Government was arguing against the spending restraint put in place by the UK Government, whilst at the same time welcoming the reducing deficit that was shown in GERS in some years (when this was basically a consequence of austerity).

We look forward some of the greatest hits coming out once again this week – even if consistency and logic is probably not high on the list for politicians’ statements on GERS Day. We live in hope though, and as ever – we’ll be here next week to point it out.

Authors

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.