The Scottish Government released the first estimate of GDP for quarter 2 of 2023, and it’s not great news. Scotland’s onshore GDP was flat in both May and June, after falling 0.3% in April, resulting in a fall of 0.3% for the quarter relative to the three months to March. This compares with quarterly growth of 0.2% for the UK on the same vintage of data, as released a couple of weeks ago.

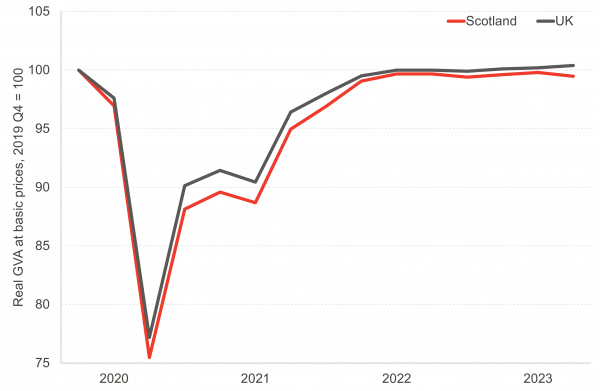

Chart: Scotland and UK real GDP

It may seem confusing when multiple forms of GDP are quoted – after all, isn’t GDP just GDP? – but not all of them are comparable with one another. Some measure slightly different things, and they can differ slightly especially for immediate readings. So on the measure of GDP used by the Scottish Government (gross value added at basic prices, if you must know!), the UK as a whole has now overtaken its pre-pandemic level and is now 0.4% higher than in quarter 4 of 2019. Scotland, on the other hand, remains 0.5% below that quarter’s reading, and the fall in Q2 of 2023 has moved it slightly further away from the pre-pandemic peak.

What drove the fall in GDP in quarter 2?

Breaking down the headline growth figure into different industries can help us understand what sectors have been driving Scotland’s performance, and how those compare with the UK as a whole.

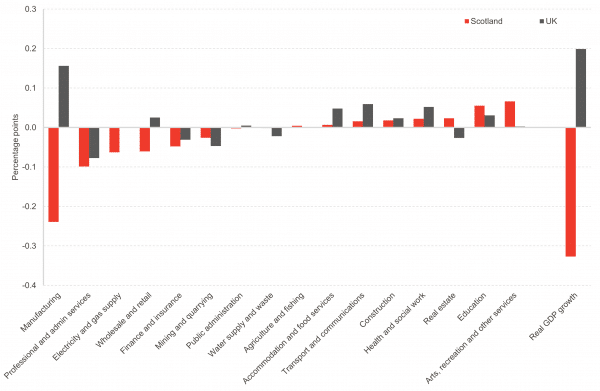

Chart: Contributions to real GDP growth in Q2 2023 by sector

The contrast is pretty clear at first glance. Manufacturing output fell considerably in Scotland from April to June, accounting for nearly three quarters of the fall in GDP, whilst the reverse story is true for the UK as a whole – and in pretty much the same proportion.

Professional and administrative services weighed down on GDP growth in both cases, and by similar amounts. Electricity and gas supply also contributed negatively to Scotland’s GDP, which might be linked to the warmer weather, especially in May and June.

But part of the story is also the smaller positive contributions of some important sectors relative to the UK as a whole. Accommodation and food services, transport, construction and health and social work together account for over a quarter of GDP, and growth in those was considerably slower in Scotland than for the UK as a whole.

The sectoral breakdown also helps explain the performance of the Scottish economy since the pandemic. Manufacturing output is still 8.4% lower than it was in Q4 2019. The numbers are similar for electricity and gas supply (-8.7%), accommodation and food services (-7.1%), health and social work (-6.8%) and arts, entertainment and recreation (-6.7%). So despite strong output growth in sectors such as construction (9.3%), information and communication (12.7%) and transport (6.4%), Scotland’s economy remains 0.5% smaller than it was three and half years ago.

An update on our hospitality industry research project

As part of our 3-year hospitality project, Serving the Future, we published a briefing on pathways into the hospitality industry and skills gaps in the workforce. This work came out of a discussion with a small group of employers in the industry who were frustrated with the educational landscape. This perspective was echoed in the Scottish Government’s Skills Delivery Landscape Review.

Our analysis found significantly higher skills gaps in the hospitality industry compared to the rest of the economy, though the survey data doesn’t show how crucial these skills are in employers’ opinions. What we found surprising was that despite higher skills gaps, workers in elementary occupations in hospitality tend to be more educated than those in other industries. This mismatch between education and skills is resulting in increased workloads for staff in 70% of hotels and restaurants surveyed. Read the full report here.

We hope you get to enjoy what is expected to be a weekend full of sunshine and good weather!

Authors

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.

Chirsty is a Knowledge Exchange Associate at the Fraser of Allander Institute where she primarily works on projects related to employment and inequality.

Allison is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in health, socioeconomic inequality and labour market dynamics.

Mairi is the Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, she was the Deputy Chief Executive of the Scottish Fiscal Commission and the Head of National Accounts at the Scottish Government and has over a decade of experience working in different areas of statistics and analysis.