Productivity has once again jumped back up to the top of the news agenda.

UK productivity growth remains exceptionally weak. And as we discussed in our Budget Briefing event on Friday, the decision by the OBR to revise their forecast for productivity has had a major impact on the outlook for the UK’s public finances.

But what about productivity in Scotland? Scotland had been catching up with the UK – at least until 2015. But as we highlighted in a recent blog, the latest figures show that Scottish productivity has since slipped back, with output per hour down 4% on where it was at the end of 2015. The next set of official comparisons between Scotland and the UK will be published in January 2018.

In this blog, we unpick recent trends to see what had been driving this relative improvement in Scotland vis-à-vis the UK up until 2015. Did it reflect an improvement in Scottish efficiency per se or is something else happening at the UK level?

We show that the key reason for Scotland ‘catching up’ with the UK does not appear to be strong growth in Scottish-specific productivity (which is relatively obvious given the fragile economic growth that we have seen recently). Instead, it is because the UK has been creating jobs at a much faster rate.

Why does this have an impact on productivity? Remember, productivity is the ratio of output to labour input. So, if the number of people working is increasing faster than the growth in output, the average contribution of each worker (or hour worked) will fall. With Scotland creating fewer jobs, Scotland’s relative productivity compared to the UK will improve.

Whether or not this form of ‘catching-up’ is a good thing is open to debate.

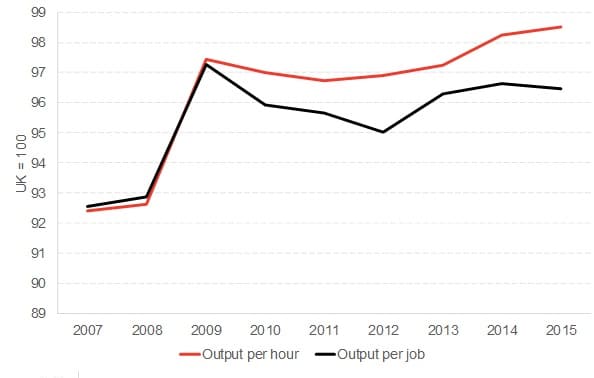

Figure 1 shows Scotland’s position compared to the UK in terms of output per hour and output per job since 2007. The closer each line gets to 100, the more closely Scottish performance is matching that of the UK as a whole. As the chart highlights, both output per hour and output per job were around 92½% of the UK in 2007 before rising to either 98½% (in the case of output per hour) or 96½% (for output per job) by 2015.

Figure 1: Labour productivity – Scotland vis-à-vis the UK

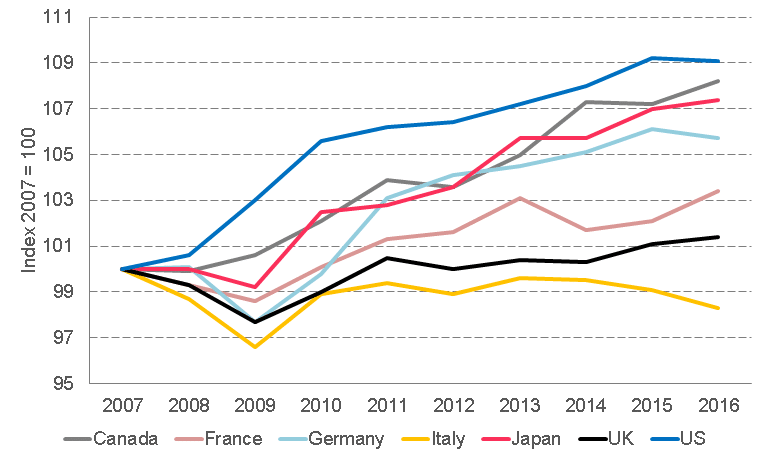

But the UK’s productivity performance remains dire as Figure 2 illustrates. Among major advanced international economies, only Italy has seen worse productivity performance since 2007.

Figure 2: UK and other major economies GDP per hour

Unpicking the drivers of productivity in Scotland and the UK

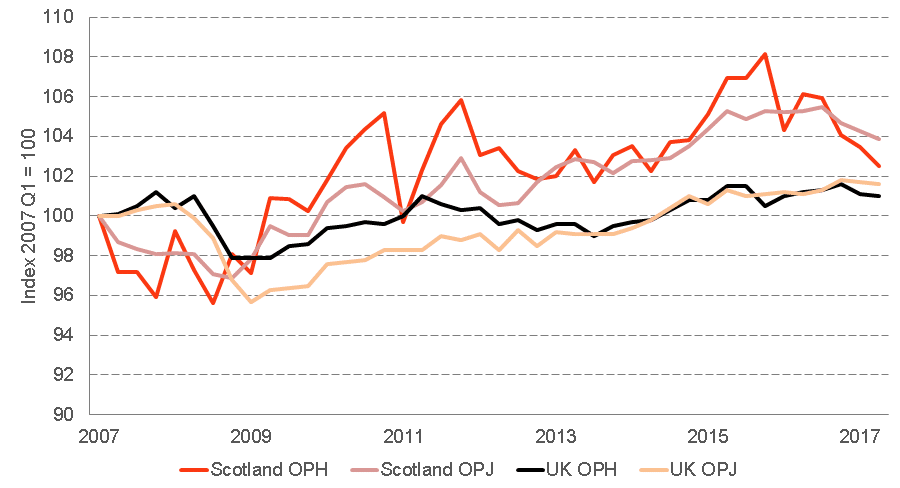

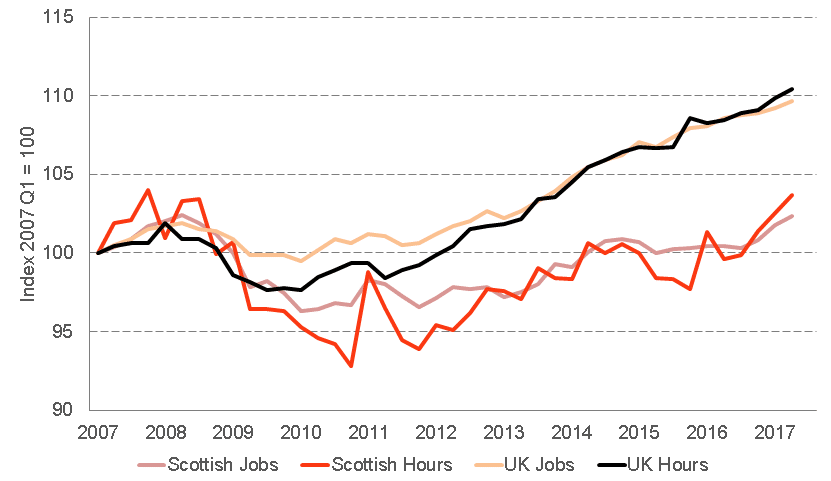

To unpick the aggregate moves in productivity, Figure 3 shows how each of the two main measures of labour productivity, output per hour worked (OPH) and output per job (OPJ) have changed in Scotland and the UK since 2007.

Figure 3: Labour productivity growth in Scotland and the UK

It is clear that Scotland’s output per hour worked and output per job had grown faster than those of the UK up to 2015, hence we saw a convergence between Scottish and UK productivity.

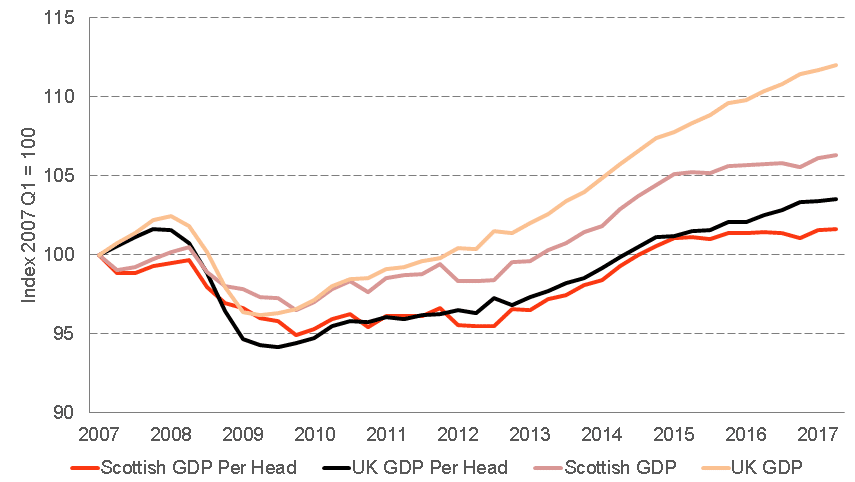

But it is also the case that Scotland’s GDP (i.e. Output) growth has been slightly weaker than the UK over the same period. The gap is greatest in terms of aggregate GDP. With the UK having much stronger population growth, the Scottish position is healthier in terms of GDP per capita (indeed the relative position for Scotland looks slightly better than the UK if 2008 is taken as the starting point rather than 2007).

Figure 4: Growth in GDP per capita in Scotland and the UK

But whatever base year we look at, we can conclude that – since 2007 or 2008 – there isn’t much evidence to suggest that Scotland has dramatically out-performed the rest of the UK in terms of overall economic growth.

Why then has Scotland caught up with the UK in terms of productivity?

The driver of convergence in productivity between the UK and Scotland is not a much faster rate of output growth per-capita, but instead the fact that the growth in hours and jobs in Scotland has been less than the growth in hours and jobs at the UK level.

Figure 5: Scottish and UK growth in hours worked and jobs

As Figure 4 highlighted, with the gap much larger in terms of total GDP as opposed to GDP per capita, a key driver for this will be faster population growth in the UK than in Scotland. As a result, the UK must be creating more jobs than Scotland.

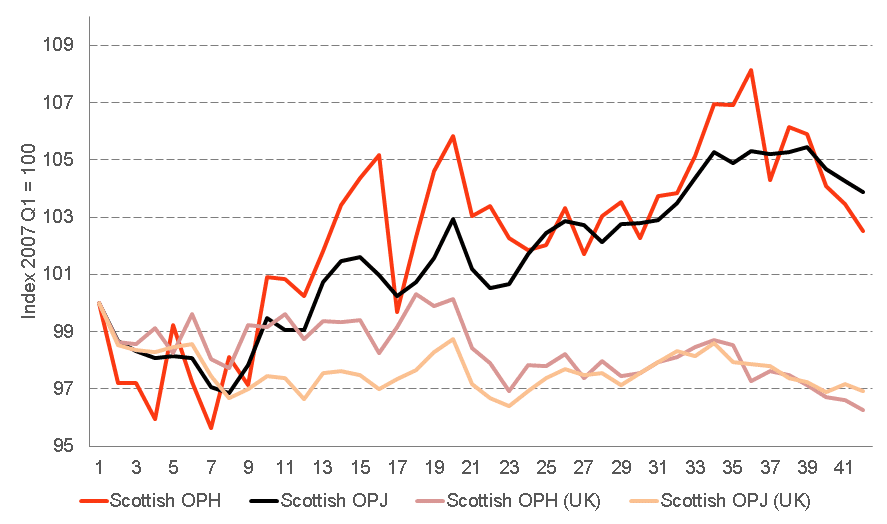

To show how this will have had an impact on the productivity results, in Figure 6 below we calculate Scottish productivity on the basis that Scotland had matched the growth in UK jobs and hours worked since 2007. We then compare this to output per job and output per hour estimates using the actual growth in Scottish jobs and hours.

Figure 6: Scottish productivity growth under alternative growth scenarios for hours and jobs

The red line shows actual output per hour in Scotland, while the pink line shows the evolution of output per hour assuming that growth in the number of hours worked in Scotland had tracked the UK. The black line shows output per job in Scotland based on the actual data, and the yellow line shows what would have happened to output per job in Scotland if job growth in Scotland had matched job growth for the UK as a whole.

As can be seen, had Scotland matched the growth in jobs or hours worked in the UK – for the same level of output growth – productivity would have fallen.

Given that the relationship between GDP and labour input is a complex one, this is clearly just one illustrative scenario (assuming that Scotland matched the UK on growth of jobs and hours worked, but didn’t see any improvement in GDP growth). Nevertheless, it illustrates the fact that had Scotland seen faster growth of hours and jobs – and more in line with the UK – the gains in productivity would have been lower.

A more general issue emerges -of course- about the types of jobs being created. Job growth can comprise all combinations of productivity levels, the key to improving productivity performance is to see sustained increases in the number of high productivity jobs.

Final thoughts

A more productive economy is clearly an important objective.

But – at least in the short-run – there can sometimes be a trade-off between greater productivity and better labour market outcomes (i.e. more jobs). Clearly we would wish to have more people in work and a more productive and faster growing economy. Sometimes however, the rate of jobs being created may outpace growth in the economy, particularly if the size of the population is growing quickly.

It is this phenomenon that appears to be driving the relative catch-up we have witnessed in recent years between Scottish and UK productivity (rather than a fundamental change in Scottish productivity).

In short, both economies have had broadly the same growth in GDP per capita since 2007. But what we have seen is a greater number of jobs being created in the UK than in Scotland. This shows up as faster employment growth and a greater number of hours worked.

For a given level of output this means that relative productivity in Scotland must ‘catch-up’ with the UK.

This serves to illustrate that policymakers need to be careful when using phrases such as welcoming ‘strong productivity growth’ or ‘robust labour market outcomes’, as there can be – at least in the short-term – a trade-off between the two.

This analysis also suggests that care needs to be taken when using recent trends for Scottish and UK productivity as a guide to future performance.

Improving UK and Scottish productivity requires growth in jobs that are more productive than we have at the moment. This means that beyond focussing on the headline employment indicators we need to think more about wider labour market issues like job quality.

The UK Government’s industrial strategy announced today is the latest attempt to provide the business and economic environment to support the development of more high productivity jobs. Whether it succeeds in boosting UK/Scottish productivity will depend as much on the extent to which it as able to garner a broad base of support throughout industry, academia and wider society, as it will on the effectiveness of its delivery.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.