Yesterday’s budget confirmed that the £20 a week increase in Universal Credit is being extended until the end of September 2021. This uplift was brought in last April to help with the impact of the pandemic at the same time as other measures such as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS, or furlough) and the Self Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) and will be removed at the same time as these temporary schemes.

The timing of removing the Universal Credit uplift has been something that a number of organisations have argued against on the basis of the impact it will have on those already on low incomes. For example, estimates from the JRF predict that this will immediately pull 500,000 more people in the UK into poverty.

Differences of opinion on whether ending the uplift in September is the right course of action will depend to some extent on prior views on the role of the state and the support that those on low incomes should receive. Some indeed argue that the uplift should be made permanent, and others disagree. We do not take a view on that wider debate here.

Here we focus on the rationale and risks of ending support in six months-time. For example, how will people be able to respond to this fall in income and what are the wider economic impacts?

Potential for harm

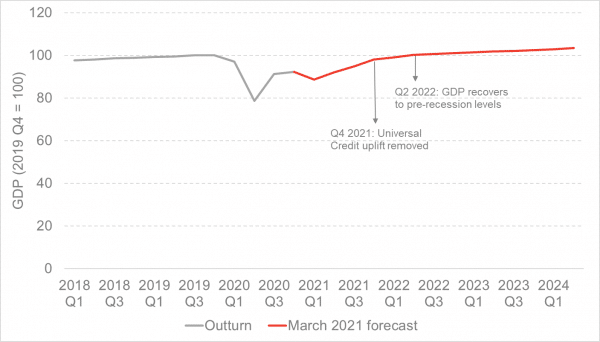

A fall in income is likely to translate to lower spending in the economy, clearly something that is not ideal during a recovery phase.

Chart: UK real GDP forecast

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility

The extent of this pass through to the economic growth depends on the amount of spending vs saving that goes on in low income households. If people are stuffing the extra £20/week under the mattress, then stopping the additional payment may not have much of a direct impact on spending. However, if the money is being spent in full – and the evidence on this is that people on lower incomes do spend a high proportion of their income[1] – then this will translate into a hit to GDP.

Taking money away from people on low income also rings alarm bells in terms of poverty and destitution. Any period living in poverty can set off a catalogue of adverse events for adults and particularly children, such as poorer future health and lower educational attainment.

Unless of course, individuals can replace this income by increasing their earnings. Is this likely to happen?

Moral hazard in a time of Coronavirus

Moral hazard is a term used in economics to describe an unintended consequence of providing insurance – both private insurance and social insurance. If insurance exists to protect an individual against a harmful event your incentives to avoid the harmful event (in this case unemployment) are smaller than if you had to shoulder the entire cost by yourself. Therefore, the higher the compensation, the less incentives you have to secure employment and taking it away may spur people into action to replace their lost income.

There is evidence to support that increases in benefits lead to a reduction in labour supply[2], but less understanding of why. There are a number of barriers that are often not possible for an individual to overcome, for example, childcare, transport difficulties, ill health and a lack of available suitable employment. All of these have been exacerbated during the pandemic.

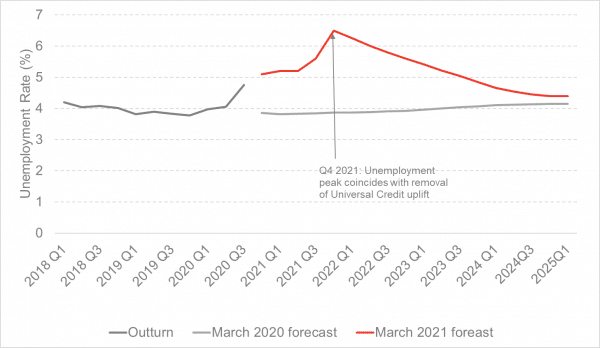

Are these factors likely to lift 6 months from now? Some of them hopefully will, but the biggest uncertainty is probably over the labour market. Indeed, unemployment is not expected to peak until Q4 2021, just as the Universal Credit uplift is being taken away, and it will be years before the economy is expected to have returned to previous levels of unemployment.

Chart: UK unemployment forecast

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility

It appears that the Chancellor is taking a gamble that the labour market will be robust enough to take more people into work (or find more hours, given that Universal Credit is an in-work benefit too).

Risky business

As already noted, there are different opinions on the rights and wrongs of social security and the levels that should be available long term. We are taking as given that the payment will be withdrawn at some point. However, there are clear risks around timing. This will also be a period when people who were getting support under CJRS and SEISS also risk finding their income fall away from them. If their jobs do not return, it will be a harder landing for them without the £20 uplift available to them.

The removal of the uplift is estimated to take about £3bn out of the economy. This of course is £3bn that the UK won’t have to borrow, but with the recovery likely to be precariously balanced, and with borrowing costs so low, the fiscal cost perhaps should not be the primary concern.

In Scotland, the introduction of the Scottish child payment, which is in essence a Universal Credit top up for families with children (although only those under 6 at the moment) will offset the reduction for some. The Scottish Government could decide it needs to do more in order to have more certainty over meeting it’s child poverty targets in 2023/24. Unlike with the UK, Scotland can’t borrow to fund this, and would need to allocate money from elsewhere in its budget to do this. We expect this issue to be debated in the next couple of months leading up to the election.

[1] See review of evidence on Marginal Propensity to Consumer contained here: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/strengthen-social-security-stronger-economy

[2] Meyer 1981 produced evidence from a quasi experimental study on this in the US available here: https://www.nber.org/papers/w3159. More recent evidence from the UK finds some positive and negative impacts depending on the structure of the support – for example Brewer et al (2006) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927537105000928#sec2

Authors

Emma Congreve is Principal Knowledge Exchange Fellow and Deputy Director at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Emma's work at the Institute is focussed on policy analysis, covering a wide range of areas of social and economic policy. Emma is an experienced economist and has previously held roles as a senior economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and as an economic adviser within the Scottish Government.