Today we published our final Economic Commentary for 2019.

Here we summarise the key points.

- Tomorrow we will get new GDP data for Scotland – covering the 3 month period to September

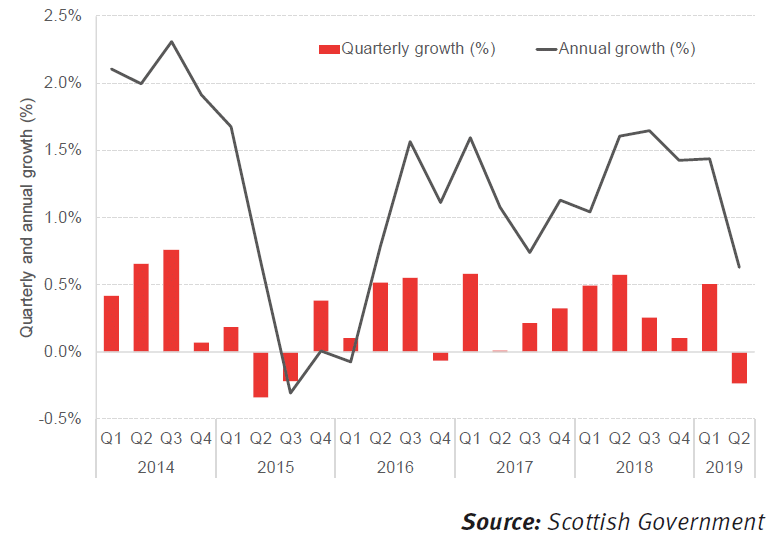

Chart: Scottish growth since 2014 – year and quarter %

The latest data suggests that the economy will have bounced back somewhat (and thereby avoid a technical recession) after a slip-back in Q2 – following the unwinding of stock-piles in the run-up to the first Brexit deadline.

It will be important therefore not to read too much into one quarterly set of results. Instead, focus should be on the longer-term. This is likely to show that growth for the year as a whole is expected to come in once again at around 1% – marking a further year of disappointing below-trend growth for the Scottish economy.

- Whilst the Scottish and UK economies have seen particularly weak growth in recent times, we are not alone.

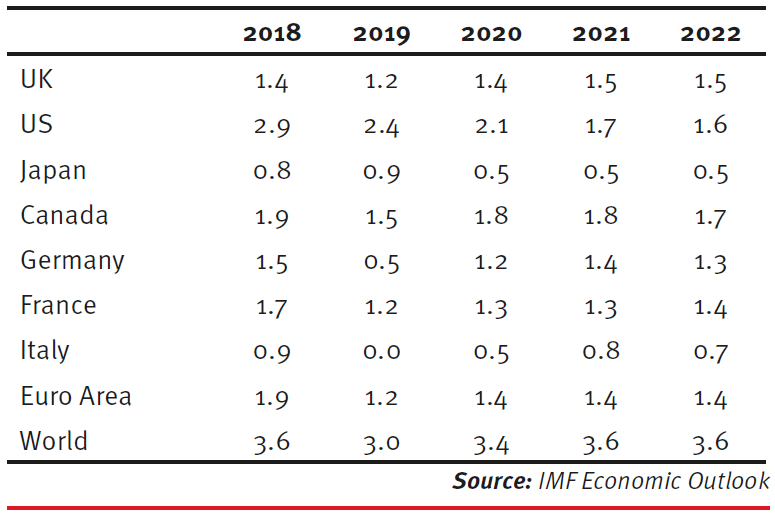

Table: IMF forecast growth rates (%), 2018 to 2022

2019 is on track to be a particularly downbeat year for the global economy, with most major economies growing more slowly this year than last.

Whilst there are some particular reasons why this year has turned out to be so weak – most notably rising global trade tensions – it would be a mistake to believe that these challenges are recent or likely to disappear in the immediate term

- Indeed, looking at a longer time horizon, advanced economies have seen growth rates much lower over the last decade that are well below past performance.

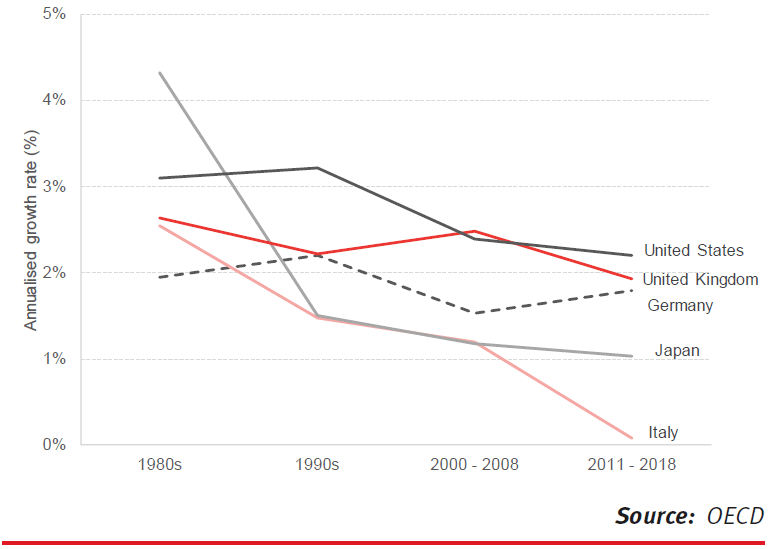

Chart: Real annualised GDP growth by decade, 1980 – 2018

This reflects, in part, a series of structural challenges – such as ageing populations and weaker technological diffusion – but may also be the result of some unintended consequences of key macroeconomic policy decisions.

- Since we published our last Commentary in October, the most recent data for the UK has continued to paint a fragile picture.

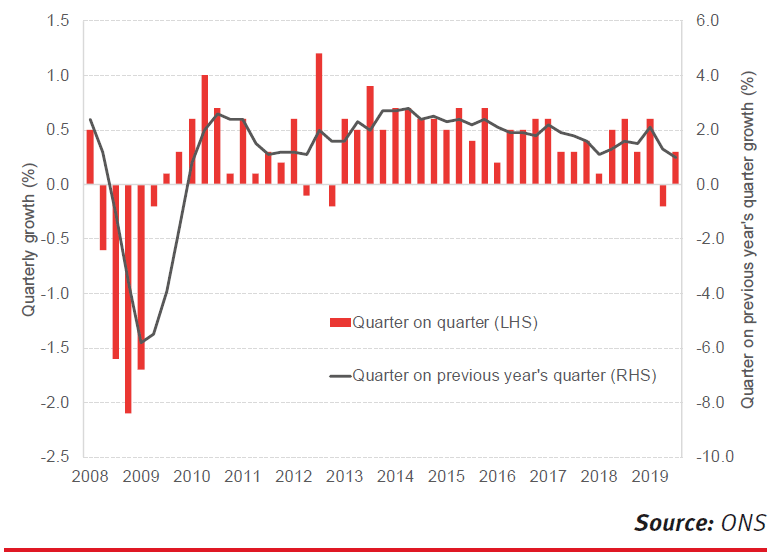

Data for Q3 showed growth bouncing back after declining in Q2.

Chart: UK real GDP growth, Q1 2008 – Q3 2019

But figures published just last week covering the month of October shows growth now flatlining at best.

- At the centre of this has been the exceptionally weak performance of business investment – which has barely shifted since the EU Referendum in 2016.

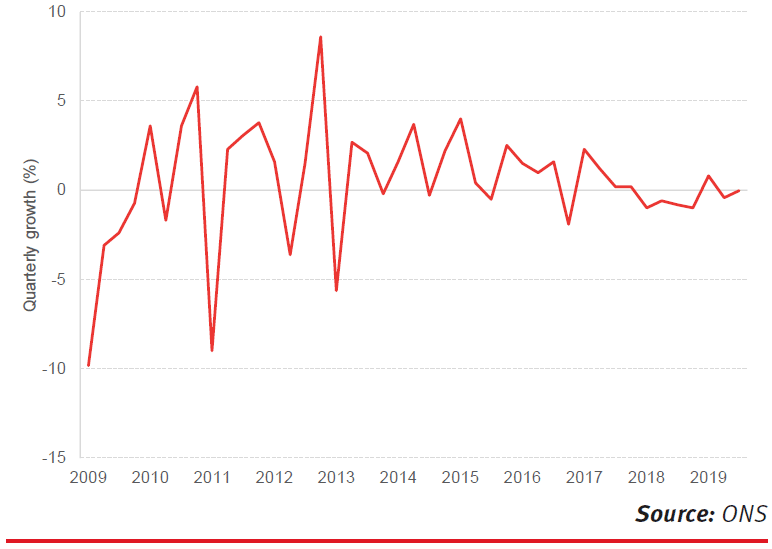

Chart: UK business investment, Q1 2009 – Q3 2019

The hope is that – whether or not you agree or disagree with the UK General Election result – the removing of at least one element of short-term uncertainty may help to unblock some of this investment.

Of course, the long-term future of the UK economic policy – and crucially the question of whether or not the UK can secure a beneficial trade deal with the EU by the 31st December 2020 – remains highly uncertain.

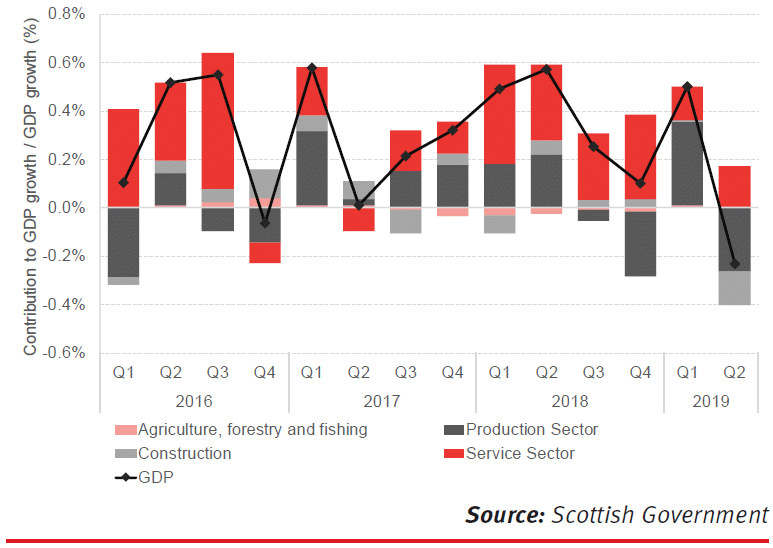

- Such trends are mirrored at the Scottish level – with volatile data shifting the quarterly trends around significantly, but the key underlying performance still well below trend

Chart: Composition of economic growth in Scotland, Q1 2016 – Q2 2019

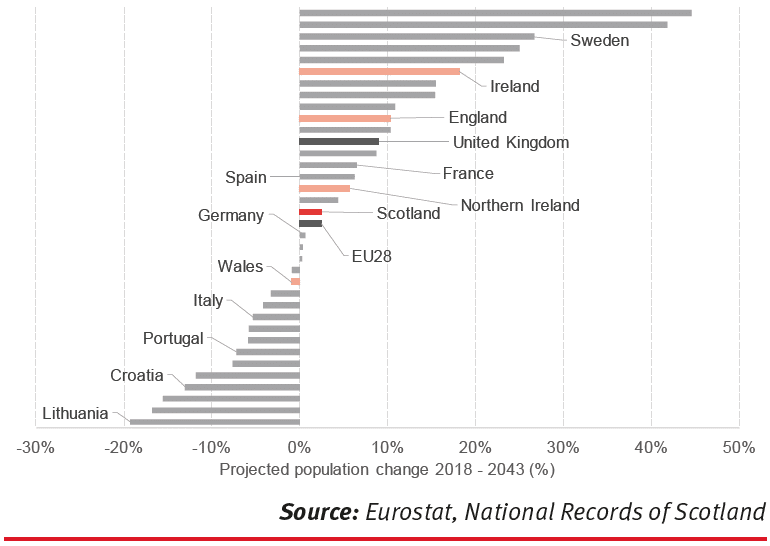

- Recent debates have tended to dominated by Brexit and the consequences for the immediate performance of the Scottish economy. But it’s important not to lose sight of long-term structural changes that will shape the future path of our economy.

In this commentary, we cover the issue of our demographic trends – both with a summary in the outlook section and the text of a speech by our Director Graeme Roy to the David Hume Institute.

Both discuss the particularly acute challenge that Scotland faces, relative to the UK as a whole with a much more precarious outlook for our total population and working age population than England.

Chart: Projected change in population by EU country, 2018 – 2043

This is the key reason why economists are so concerned about the potential negative hit to Scotland’s economy from any change in migration patterns post-Brexit that may limit migration to Scotland.

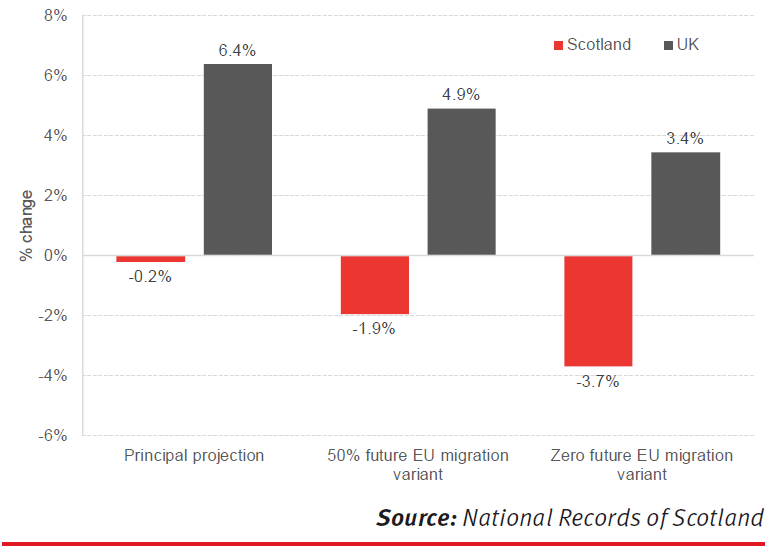

Chart: Change in working age population under different EU migration scenarios, 2018 to 2043

For example, any sharp fall in migration numbers from the EU would see Scotland’s working age population (even accounting for a rising retirement age) fall sharply, but this would not occur at the UK level.

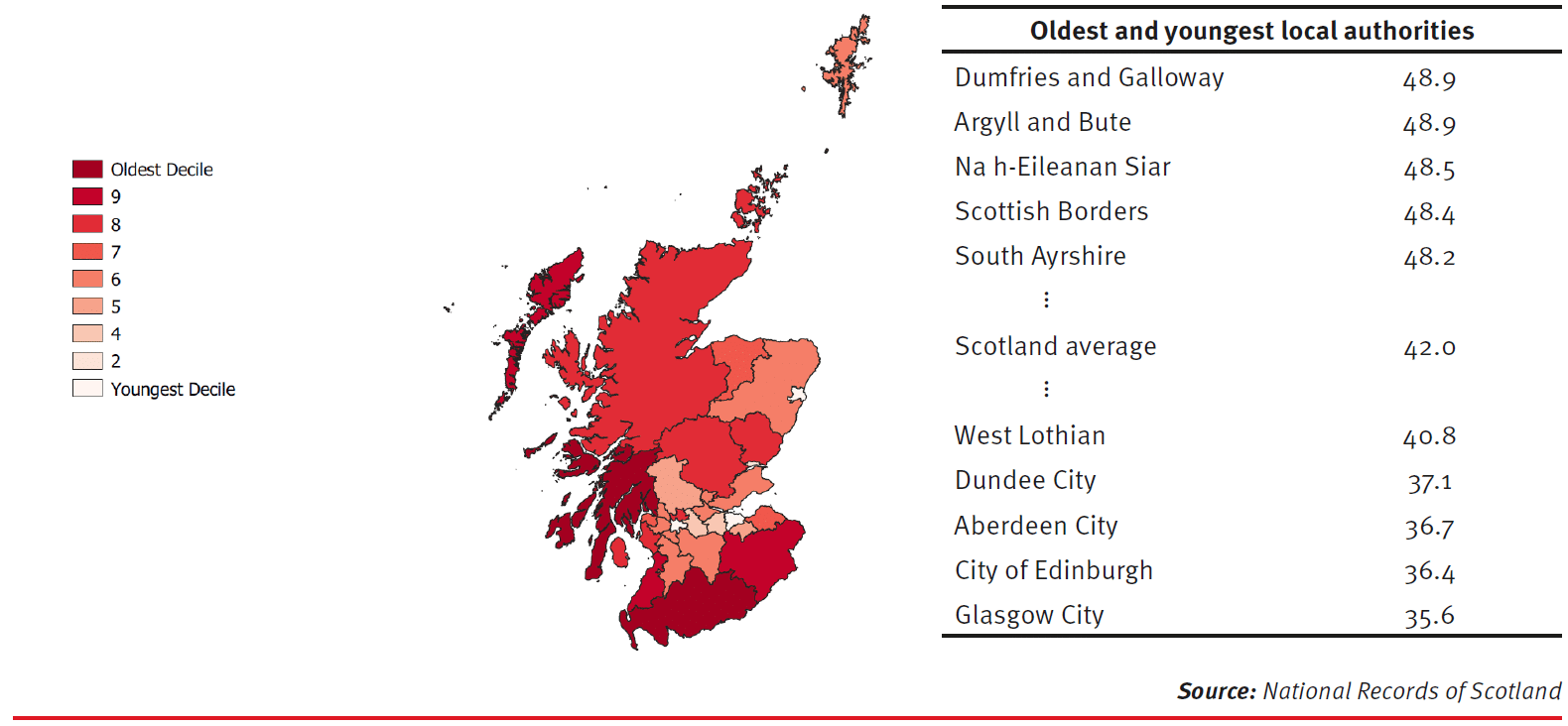

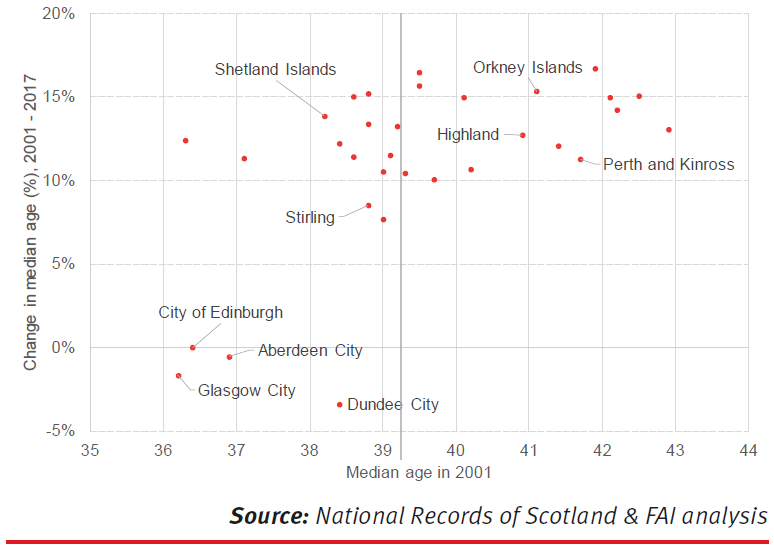

- Of course, within Scotland there are significant variations in the population outlook. Some parts of our country already have populations that are much older than the Scottish average but are also ageing more quickly.

Chart: Median age by local authority, 2017

The long-term sustainability of some communities is a real challenge and will only become more acute in the next few years.

Chart: Change in working age population by UK nation, 2018 – 2043

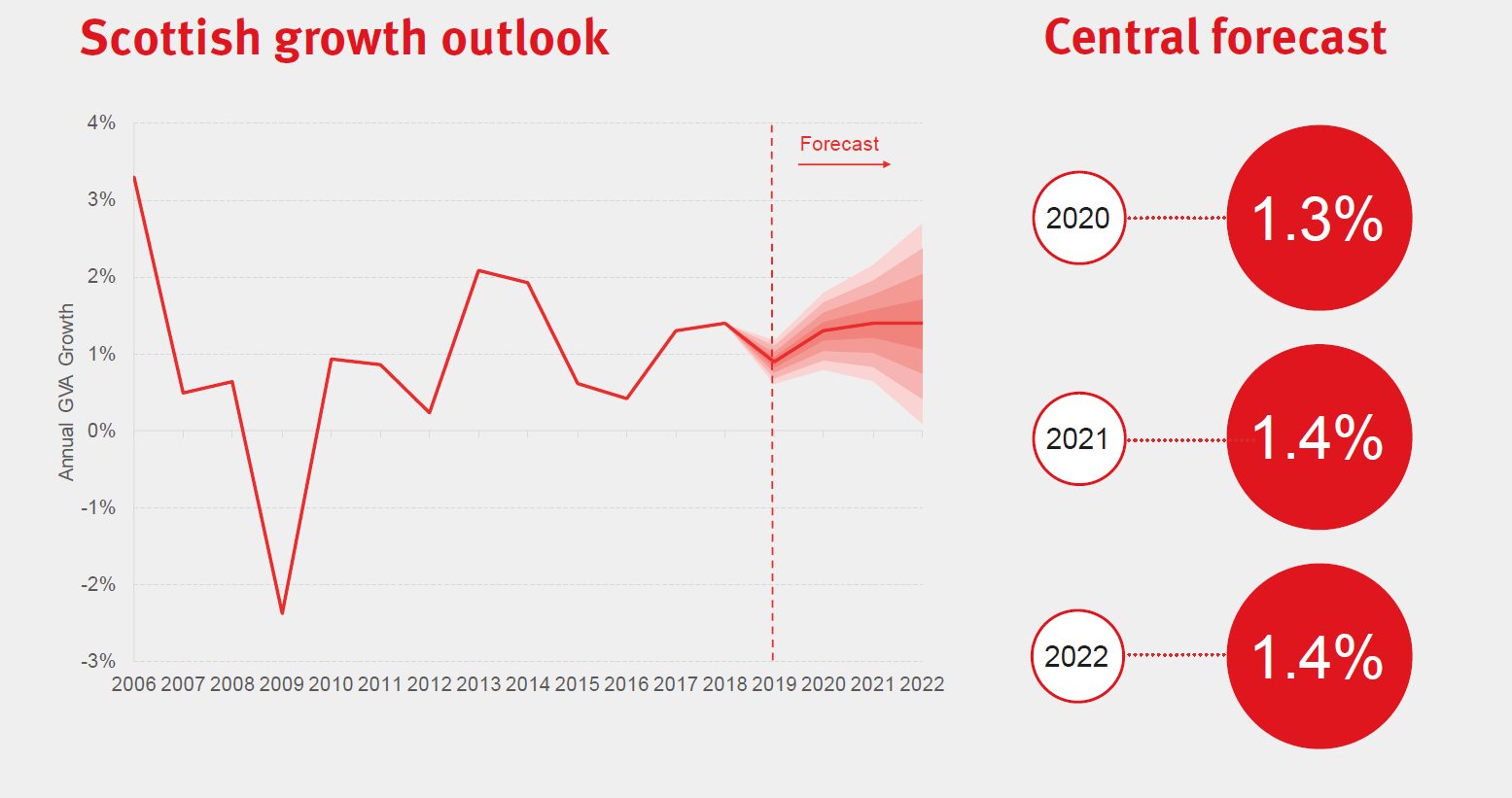

- On balance, we continue to forecast that the Scottish economy will grow next year, but that growth will remain below trend

Economic forecasting at the current remains challenging, even in the light of some resolution to the recent uncertainty as a result of last week’s general election.

The removal of – at least some – uncertainty regarding both the political make-up of the UK Parliament and the timing of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU (and the avoidance of ‘no deal’) should help to restore some confidence and unlock investment.

At the same time, the promised fiscal stimulus from the new UK Government should help boost demand in the short-turn.

However, against this there are risks. The global outlook remains more challenging than it has in the recent past. Moreover, only the timing and terms of the UK’s exit from the EU have been agreed. The hard work of securing a future trade deal now has to be completed (in just 12 months). Should this go awry, then the UK may still end up with ‘no deal’ by default on 1st January 2021.

- In our policy context section, we analyse the outlook for the – now delayed – Scottish budget for 2020 to 21.

As we have highlighted before, Mr Mackay faces some challenging income tax reconciliations next year.

However, his budget will be boosted significantly by additional Barnett consequentials flowing from pre-election spending promises made by the UK Government.

Of course, the budget is just one important debate set to take place in 2020.

Alongside a renewed debate around independence, we enter the final calendar year before the next Scottish election where the scrutiny of the current government’s handling of the economy will no doubt intensify.

Throw in major policy issues such as the climate change emergency continuing to be high-up on people’s consciousness, and it’s clear that the next few months promise to be an important and fascinating time for the Scottish economy.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.