How to reduce government spending in the least bad way

Recent events have placed great pressure on both the UK and Scottish governments to find savings to public spending. This was the case for the Scottish Government even before the mini-budget turmoil began, with the Deputy First Minister John Swinney announcing at the beginning of September that savings of at least £500m would be needed in response to the pressures on the Scottish budget.

The cuts announced in early September include £53m of employability support spending.

No one doubts that inflationary pressures on the wage bill increase the ever-present need to prioritise. A fixed in-year budget means that the potential for overspend needs to be managed.

Ideally, budget cuts are made based on impact appraisals so decision makers can fully understand the consequences of their decision, and the rationale is transparent to the public.

Next week’s budget review will provide an opportunity to fully explain the rationale behind the decision about employability support and to outline the expected impact. Here we lay out our analysis of the potential impact and the questions we would like to see answered.

What is employability support?

Employability services provide individual support to people who wish to work but face barriers to doing so. These barriers are varied, multiple and unique to each person, but include lack of requisite skills or experience, logistical problems (e.g. accessible transport), lack of confidence due to a period out of the labour market, or the need for additional support for job applications and interviews.

Local authorities have long provided employability support as part of council services. In 2016 the Scottish Parliament received new devolved powers (and funding) to deliver services previously operated in Scotland by the DWP.

What has been the rationale for employability support in the past?

In the strategic plan for employability support, first published in March 2016, the Scottish Government committed to a plan that “better support[s] its most vulnerable citizens into sustainable employment.”

Follow-up reports and plans repeat the intention to support people into “the right job at the right time.”

Notably, it is difficult to find any justification involving labour market conditions; rather, employability support plans tend to emphasise that some groups will always need additional and continuing support. These groups include disabled people, people experiencing homelessness, people recovering from substance abuse and people with convictions.

Additionally, employability support is frequently cited as a key component of initiatives to tackle poverty and inequality, particularly child poverty, and formed a key part of the latest Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan, published in March 2022.

What does the cut look like in context?

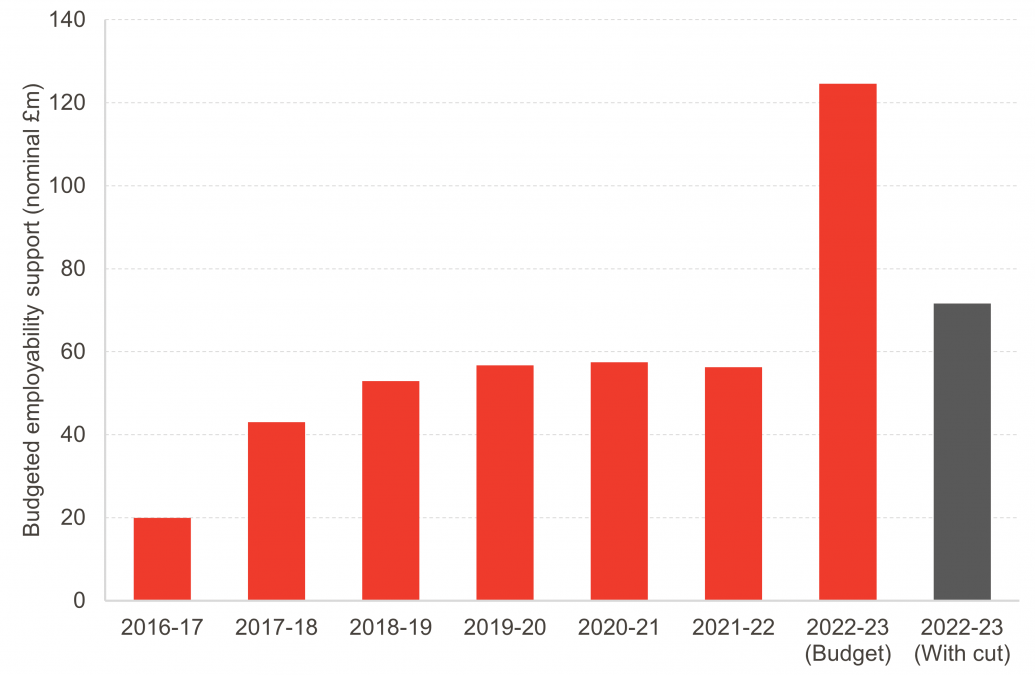

At the last budget, £124.6 million was allocated by the SG to employability and training, a rise of over £68 million on the previous year, Chart 1. The announced £53 million cut represents 43% of the amount named in the budget last year.

Chart 1: Budgeted employability support, 2016-17 – 2022-23

Source: Scottish Government

Notes: For all years except 2022-23, the amount is obtained from the following year’s budget to reflect what was actually spent on employability and training.

The amount announced last year was a significant rise on the trend since 2016-17, when employability support programmes were devolved to the Scottish Government. Thus, the recent cut places the budgeted amount for employability support back closer in line with the trend from previous budgets.

What was the rationale given?

In September, the Deputy First Minister stated, “At a time of acute labour shortages, historically low unemployment and soaring inflation, we have taken the view that we must prioritise wage increases over spending on employability…”

There is no dispute that the labour market is tight.

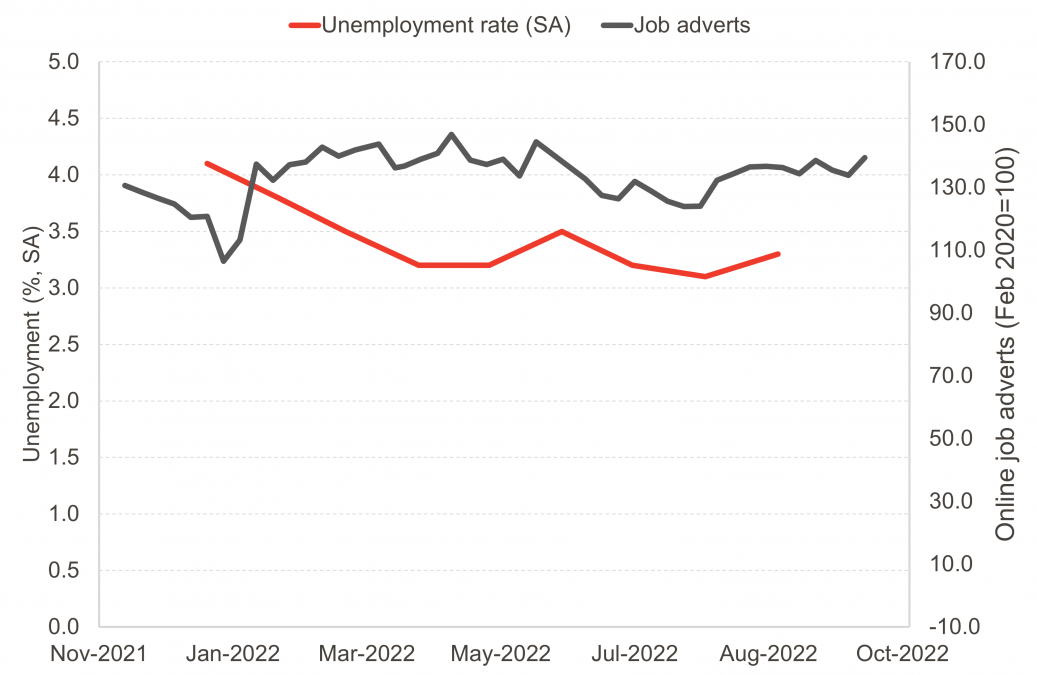

Although permanent appointments are growing, albeit slowly, there are still a very high number of vacancies, Chart 2. Simultaneously, the overall unemployment rate is low, around 3%.

Chart 2: Job advertisements and unemployment in Scotland, Dec 2021 – Oct 2022

Source: ONS

Notes: Unemployment series is rolling quarterly data with data points appearing at the end of the three-month period, Oct-Dec 2021 – June-Aug 2022; adverts series is from weekly Adzuna data published by ONS and spans December 2021 to the first week of October 2022.

Although permanent appointments are growing, albeit slowly, there are still a high number of vacancies, Chart 2. Simultaneously, the overall unemployment rate is low, 3.3% in July.

On one hand, with high vacancies and constrained labour supply, some businesses may be prepared to invest more in staff training and coaching. This may mean that some people who were previously overlooked for positions will be more successful and may not need employability services to provide the same level of support.

On the other hand, there are other barriers to the labour market that an employer can’t address alone. In these cases, reducing employability support will lead to a lower labour supply than would otherwise be the case.

Weighing public sector pay against employability

In prioritising pay, the Scottish Government are only talking about public sector staff. Public sector pay levels are a core part of the Scottish Governments response to the cost of living crisis. However, if living standards are of utmost concern, it is difficult to argue that those with a job are a higher priority than those without a job.

Data on household incomes from 2017-20 shows that 12% of working-age people in work were in poverty compared to 43% on average for those out of work. The poverty rate for public sector staff is even lower, 6% of working-age adults compared to 13% in the private sector. Given their lower income, people out of work are arguably more exposed to the current cost of living crisis.

One clarification of the process for deciding what cuts were most appropriate arose in the Deputy First Minister’s responses to questions from the Social Justice and Social Security Committee in late September.

The Deputy First Minister explained that cuts were made from money that had not already been spent or legally committed, which likely narrowed the pool of potential areas in which to reduce spending.

His answers indicate that current capacity in existing employability programmes will be maintained. It is money that has not yet been spent that is being taken back.

The expectation was that the additional money would have funded the step change in employability support for parents outlined in the latest Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan.

The funding was welcomed by third-sector organisations as previous Scottish Government analyses showed that existing programmes are not equally effective for all groups, for example single parents. It follows that the consequence of maintaining only existing programmes is that employment outcomes will likely remain comparatively poor for these groups.

Questions to be answered

Further details about which elements of employability support funding will be affected should be forthcoming in the budget review the Deputy First Minister has promised for next week.

For budget decisions, we’d usually hope to see an Equality and Fairer Scotland (i.e. socioeconomic) impact assessment to show if any groups with protected characteristics under the Equality Act will be particularly disadvantaged. This document, if produced next week, may help us understand the adverse impact of decisions made.

The wider question is what else was considered, and why employability spend was reduced over other areas. The answer may well be that employability support was one of few areas where spend had not already been committed. If that is indeed the main rationale for the cut, it would be preferable to hear that reason given outright.

The last key question regards the future legacy of these cuts. If, as currently understood, the cuts relate to the parental employability support set out in the Tackling Child Poverty delivery plan, will the funding be reinstated later? If not, what, if anything, will replace it in the drive towards meeting child poverty targets?

These are difficult questions that require answers from the Scottish Government. The same of course applies to the UK Government; the impact of proposed cuts to public spending also need to be understood, and plenty will be quick to point out negative impacts on people across the UK. From a trust and transparency point of view, it is far preferable that the ones making the decisions lay out the evidence themselves.

Authors

Emma Congreve is Principal Knowledge Exchange Fellow and Deputy Director at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Emma's work at the Institute is focussed on policy analysis, covering a wide range of areas of social and economic policy. Emma is an experienced economist and has previously held roles as a senior economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and as an economic adviser within the Scottish Government.

Hannah is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in applied social policy analysis with a focus on social security, poverty and inequality, labour supply, and immigration.