It is now a year since the first lockdown in Scotland and many are taking stock and looking back on a year like no other. The toll of the pandemic on lives has been severe. First and foremost, finding ways to limit the spread of Covid-19 has been the focus of policy makers in this year.

However, the impact of the pandemic of course goes beyond the direct health impact, and one of the groups that have well and truly seen their lives turned upside down are children.

During 2020, the Fraser of Allander Institute took part in a collaborative project looking at the socio-economic impact of Covid-19 on children over the first 6 months of the pandemic. As you would expect, children have been affected by the impacts of Covid-19 in a multitude of ways.

The project was designed to be a gateway to analysis and data on the socio-economic impact of Covid-19 on children. Starting a new piece of research can be daunting, whether you are government, third sector, an academic or private sector researchers. Our aim was to produce resources that others can use as a springboard into using these insights and/or producing new analysis on the impact of Covid-19 on children.

A year in to the pandemic, it’s worth revisiting some of the key insights this work highlighted.

Insights from the project

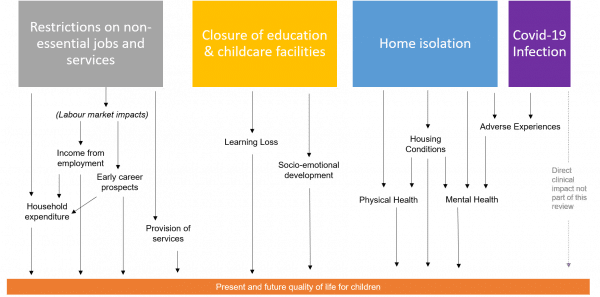

The evidence reviews affirmed how significant Covid-19 had been on the lives of children in the first 6 months of restrictions. To visualise this we produced a schematic which shows these impacts, and some of the interactions. We discuss some of the key points below.

Figure 1: Identified socio-economic impacts of Covid-19 covered in the evidence review

Closure of education and childcare facilities and home isolation

Some of the impacts on children were directly felt due to the restrictions – for example, the closure of schools and increased time spent in doors away from friends and extended family.

The impact of schools and childcare facilities closing (and reopening and shutting again!) will only be understood fully over the medium to long term, but a particular concern relates to widening inequalities due to the fact learning loss and loss of socio-emotional skills are likely to be felt more for children from lower socio-economic backgrounds. This stems from a range of potential sources, including whether or not there is suitable study space at home with sufficient access to digital resources, and the extent to which parents or other adults were able to support children’s learning at home.

The long period of enforced time spent at home without access to normal social activities is likely to have had a detrimental impact on both physical and mental health. Again, socio-economic background is likely to have led to a more detrimental experience for some children due to factors such as availability of food, heating and access to outdoor space.

A range of studies have pointed to an increase in issues around children’s mental health due to the first lockdown although there were also some positive examples for example due to more time being spent with parents and relief from the absence of stressors such as bullying at school.

Impact on family income due to the economic consequences of the pandemic

Adding to the issues faced directly by children, they will also have been impacted by the economic consequences of the pandemic via the impact on parental income. Loss of employment is a key route into poverty, and child poverty is known to have a wide range of harmful effects including on short-term wellbeing and long term educational attainment and long term health. The Coronavirus recession has been severe and the route out of it still uncertain.

Of course, policies such as furlough have mitigated much of the financial harm, and the social security system has also stepped in with additional support. But large losses of income for some households have undoubtedly occurred. In some cases, households will have been able to mitigate the loss through use of savings, or debt (although both these have implications for long term living standards). Elsewhere, there will have been reductions in expenditure on basic goods and services. Evidence suggests that this indeed become the case with food bank activity increasing markedly and our review found some evidence that families with children were more likely to be struggling compared to other types of households.

Impact on children who were already facing challenges

For children and families already facing challenges, the pandemic has thrown up a range of issues, with many yet to be resolved. Public services are a key way of trying to remove barriers faced by children due to circumstances outside their control. These barriers, if not removed, can lead to increased marginalisation, adversely affecting outcomes for the rest of children’s lives.

Some groups of children have faced specific challenges and have ongoing support needs that may have been reduced due to the lockdown. Groups such as disabled children, those with additional support needs, young carers, care experienced young people and those in contact with youth justice services have faced particular challenges. Disruption of services has been well documented, and there is some evidence on the impact this has had on children’s emotional wellbeing and mental health. Longer term impacts are likely.

There is also evidence that the pandemic increased the likelihood of a range of ‘adverse experiences’ occurring (e.g. bereavement), or the chances of these experiences being mitigated by timely intervention (e.g. domestic violence, child neglect).

More information on the project

The project was set up by the Data for Children Collaborative, a joint partnership between UNICEF, the Scottish Government and the University of Edinburgh which seeks to improve outcomes for children in Scotland and further afield. As the name suggests, the use of data is a central theme, and their collaborative projects bring in academics, public and private sector to push forward understanding and to develop actionable insights.

The collaborative project also included data scientists from Effini who put together a data catalogue of data to help researchers find information that could help with future research. We also put together a map of existing research capability of both academics and individuals who work on issues related to socio-economic outcomes for children.

All the outputs can be found on the Data for Children Collaborative’s website here.

Authors

Emma is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute

-768x432.jpg)