Today we have published our first Scotland’s Budget report – for 2016 – at an event in Edinburgh attended by all parties and representatives from Scotland’s business, third sector and public sector communities.

Scotland’s Budget: 2016 provides an objective assessment of the outlook for Scotland’s finances and the choices, challenges and opportunities facing Scotland’s new Finance Secretary.

Not everything is known with certainty but through our publication we hope to provide a solid evidence base for a frank discussion about the priorities for Scotland, including how best to use our new tax and welfare powers.

The full report can be accessed here.

Today’s report sets the context for debate. And it will be lively! The coming months and years may turn out to be the most important period of economic and fiscal policy debate Scotland has known.

Whilst the immediacy of the challenge our report sets out will fall on the Scottish Government, it is vital that political parties from all sides set out their priorities, including how they will fund new commitments, deprioritise others, and manage increasing demand on public services.

This blog summarises the key findings of our report in six charts.

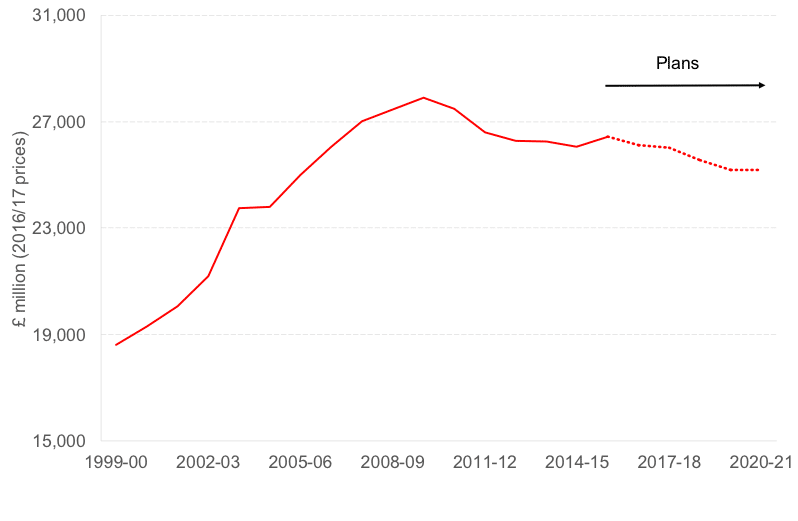

1. For the first few years of devolution, Scotland’s resource budget had been growing in each and every year. But since 2009-10 it has been falling and the Scottish Government now has a budget that is around 5% lower in real terms than they had at the start of the last parliament in 2011.

Chart 1: Scottish Government resource Budget, 1999-00 to 2020-21

Source: Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis, various years; FAI analysis of Budget documents

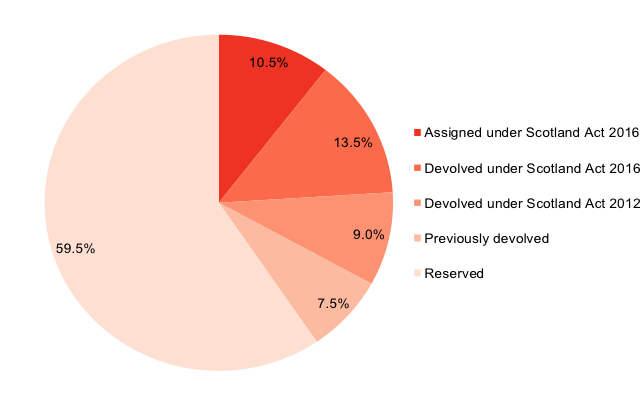

2. From next year, the Scottish Parliament is obtaining substantial new tax powers and soon around half of Scotland’s budget will be directly financed by revenues raised in Scotland. This gives the Scottish Government much greater autonomy to shape the distribution of income and the pace and type of economic growth in Scotland.

Chart 2: Evolution of Scotland’s tax powers

Source: GERS and FAI calculations

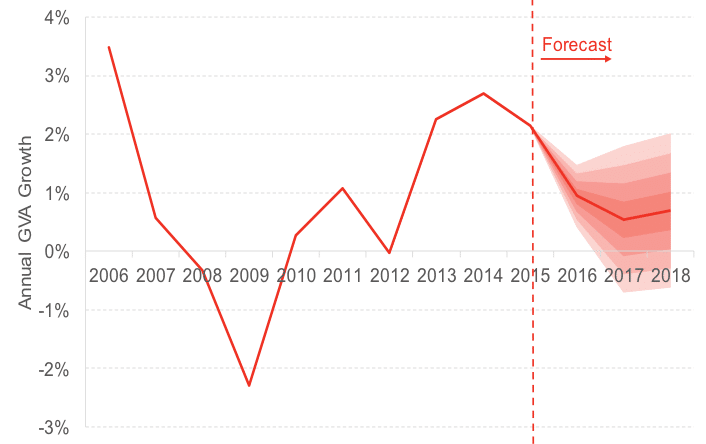

3. The Smith Commission proposals were also designed to introduce greater risk and greater reward to the Scottish budget – if Scotland’s economy performs strongly then the budget will be better off (and vice versa). However, the Scottish Government can’t control all the risks it faces – a shock to the incomes of North Sea workers is just one example of something that they can do little about.

Overall, the new powers are being transferred at a time of significant uncertainty and fragility in Scotland’s economy – see our revised forecasts here. Interestingly, in Box 1.4 in the report we briefly discuss some new modelling results which show that Scotland may be less impacted by Brexit in the long-run than the rest of the UK.

Chart 3: FAI forecasts for GVA growth: 2016-2018*

Source: FAI calculations

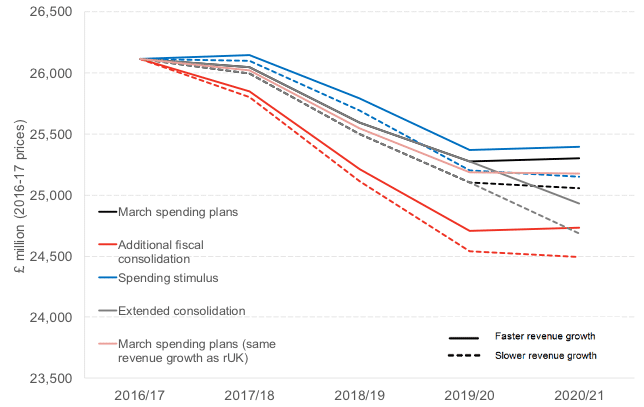

4. So with this background, our report today does two things. Firstly, we set out a range of scenarios for Scotland’s block grant from Westminster and the growth in Scotland’s new devolved tax powers.

For the block grant, whilst some may hope that Phillip Hammond’s promised ‘reset’ of fiscal policy will include a rapid reversal of planned departmental budget cuts, this seems highly unlikely – indeed further fiscal consolidation is now even more likely over the medium term as the government responds to a weaker economic outlook.

For devolved tax revenues, we offer two scenarios – one where Scotland maintains its recent better tax per head performance compared to the UK in the future and the other where the reverse is true.

In March of this year, the Scottish Government’s budget was forecast to fall in real terms by 2020-21 as result of the UK Government’s ongoing fiscal consolidation. Our new analysis suggests that the Scottish Government should be preparing for cuts of between 3% – 4% – around £1bn – over the period (and under a worse-case scenario for the block grant and devolved revenue growth have contingencies for anything up to 6% real terms fall in its spending power – around £1.6bn).

Chart 4: Scenarios for the Scottish resource budget, £m (real terms, 2016-17 prices)

Source: FAI calculations

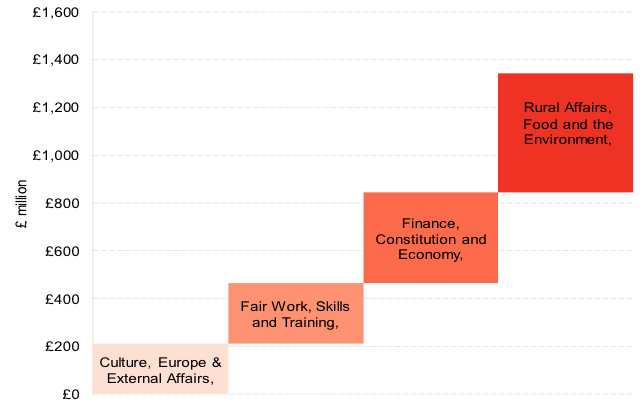

5. To put these numbers in context, a fall in the budget of £1.6 billion (our worst case scenario) would be more than the entire budgets for the Finance and Economy; Fair Work, Skills and Training; Culture and External Affairs; and Rural Affairs, Food and Environment portfolios combined.

Chart 5: Scale of the challenge: £1.6bn in context (2016-17)

Source: Scottish Government draft budget 2016-17

6. The second thing that our report does is set out the series of significant policy priorities announced to date by the Scottish Government. This includes above real-terms increases in the health budget, a protection of the policing budget, substantial new investment to tackle the educational attainment gap and a policy to transform childcare provision in Scotland – a clear statement of intent and an ambitious and bold agenda.

It will mean however, that in a world of tight budgets, delivering on these will require a tough re-prioritisation in other areas of the public sector.

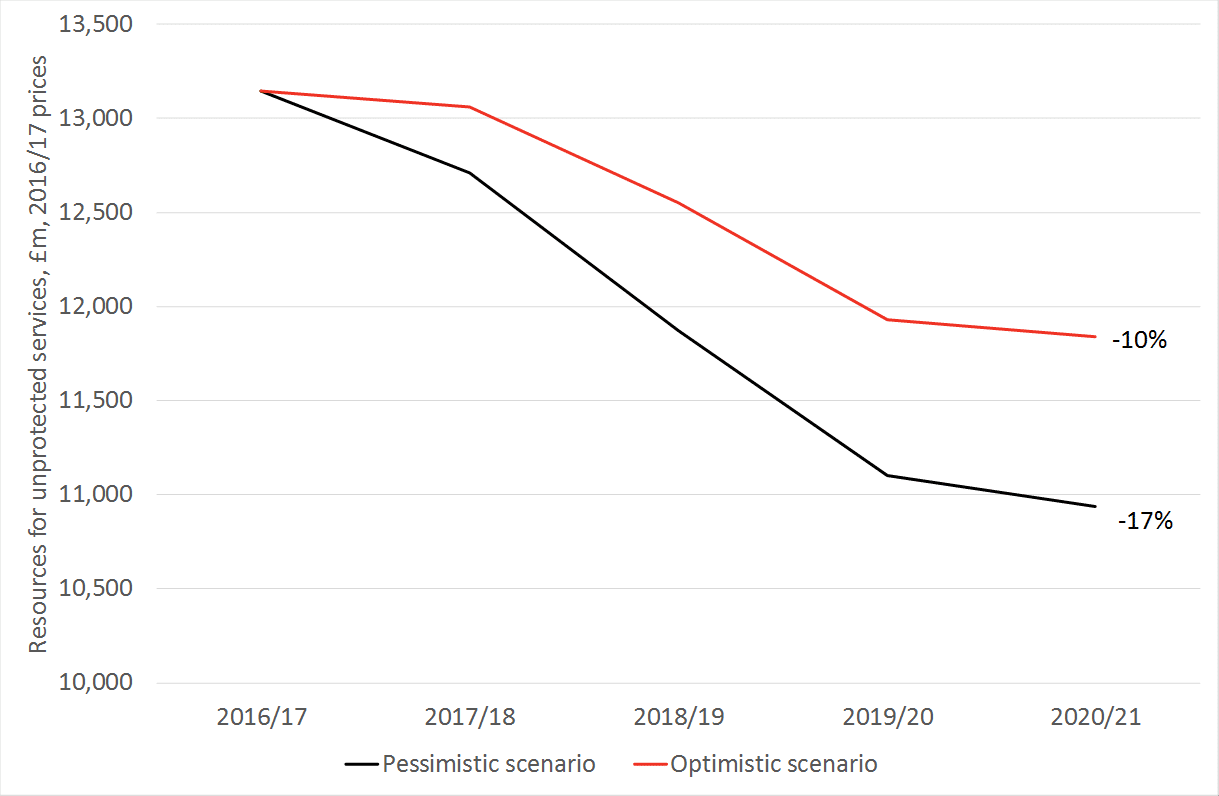

‘Unprotected’ areas of the budget will face average real terms cuts over the period to 2020-21 of between 10% – 17% (2.6%-4.5% annually), depending on the size of the Scottish block grant and the revenues from Scotland’s new devolved taxes.

Local government will likely be a key focal point. As an area of unprotected spend, the grant to local government could be cut by around £1 billion on a like-for-like basis by 2020-21.

Chart 6: Outlook for ‘unprotected’ areas of spend

Source: FAI calculations

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.