Late last month, the latest business investment figures for Scotland were published – with a reported fall of 15% over the year.

Are these figures the result of Brexit uncertainty?

If the latest business surveys are believed then this is quite likely in some instances. But a look at the data from well before the EU Referendum reveals that low levels of investment have been a feature of the Scottish economy for years.

Brexit can’t be blamed for every structural challenge that we face.

Initiatives to boost the supply of finance are to be welcomed. But it’s not entirely clear that this is the greatest barrier. In many instances, it is the demand for finance that needs to be developed and supported.

Recent trends in Business investment

Business investment is important for a number of reasons.

Firstly, it in itself is an important component of aggregate demand in the economy, particularly for sectors such as construction. Secondly, and much more importantly, investing in new plant, machinery, office-space etc., can help firms become more productive over time. Investing can also help them to innovate and access new markets.

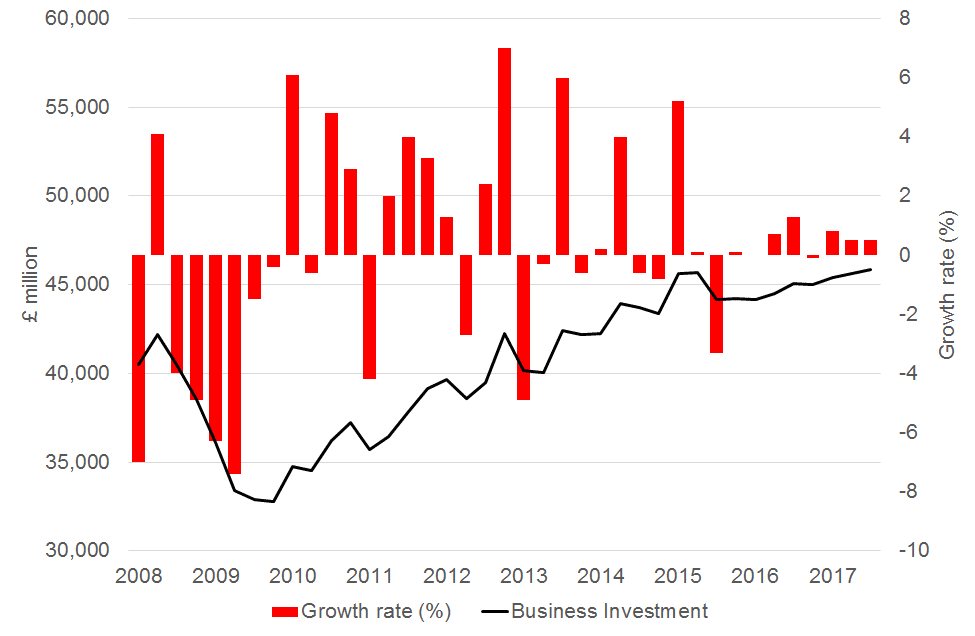

Business investment has been weak in the UK since the financial crisis. And since early 2015 that performance has weakened even further.

Chart 1: Business investment in the UK (constant prices, seasonally adjusted)

Source: ONS

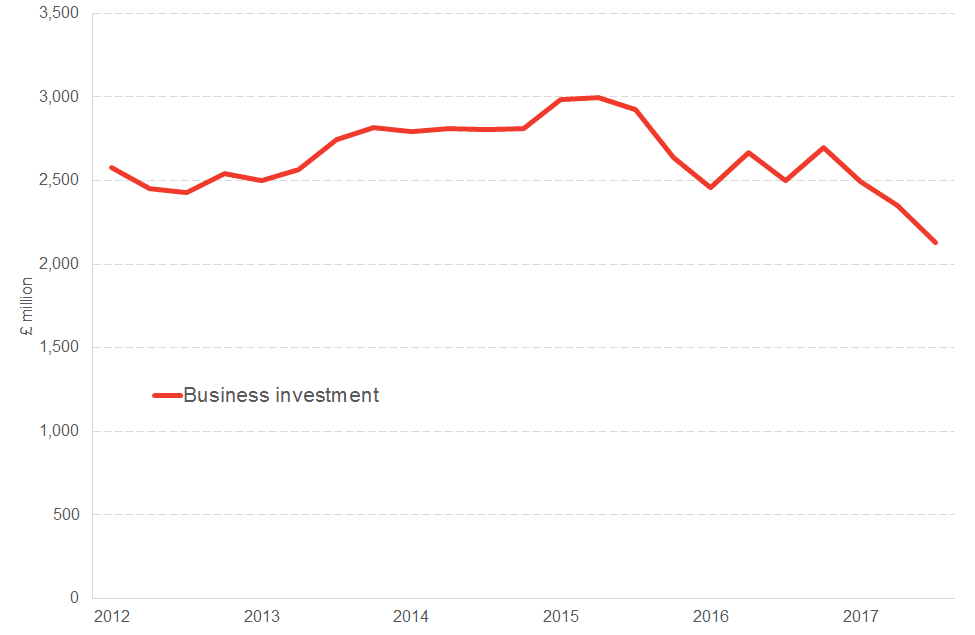

If anything, the trends in Scotland are even more disappointing.

Chart 2 shows the level of business investment in Scotland using data from the Scottish Government. Two important caveats:

- The series remains “in development” and therefore any inferences drawn have to be seen as preliminary;

- The Scottish Government only publishes the data in current prices (i.e. unadjusted for inflation).

Since 2015, business investment in Scotland has been falling. It fell around 11% in cash terms between 2015 and 2016. Since then, it has fallen further. In Q3 2017, investment is down nearly 15% compared to the same period in 2016.

Chart 2: Business investment in Scotland (current prices), since 2012

Source: Scottish Government, National Accounts

We have argued in past Fraser Economic Commentaries, that Brexit uncertainty is likely to have an impact on business investment in both Scotland and the UK.

During times of uncertainty, firms tend to postpone investments until there is greater clarity. This tends to lead to delayed investment rather than cancelled investment. Provided that business are positive about the outlook once uncertainty subsides, then investment is normally expected to bounce back. Over time, any impact of delayed investment could be relatively marginal.

But if lenders believe the ongoing environment is risky, they might demand a heightened risk premium, which results in a rise in the effective cost of capital. As a result, investment will be lower than it would have been in the absence of uncertainty. And of course, should firms believe that their growth prospects will be hampered by a major event – e.g. Brexit – then any impact of uncertainty on investment will be more long-lasting.

The Scottish Government have undertaken some analysis to illustrate the impact of Brexit uncertainty on investment in Scotland – see here. They concluded that Brexit uncertainty could reduce investment by £1bn by 2019.

Some will no doubt argue that the risks of Brexit are being overplayed. And the accuracy of the £1bn figure clearly needs to be taken with a degree of caution (and can only ever be viewed as illustrative).

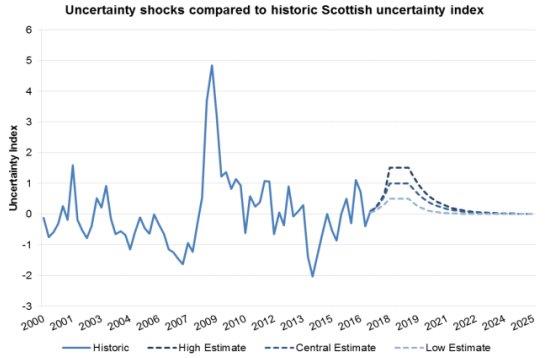

Some may even point to the Scottish government’s own uncertainty index which appears to show that current levels of uncertainty are relatively low compared to the past (i.e. compare the baseline figure of 0 for 2017 with a positive uncertainty index value through 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011 and 2012). NB: somewhat surprisingly, the measure also shows 2014 as being a period of relative certainty.

Chart 3: Uncertainty index: Scottish Government

Source: Scottish Government, State of the Economy

But it would be wrong to believe that Brexit is not having at least some impact for a great many firms. The Bank of England and business organisations have regularly warned of evidence that uncertainty is having an impact at the UK level, and there is no reason to think that Scotland will be different.

Long-term trends in business investment

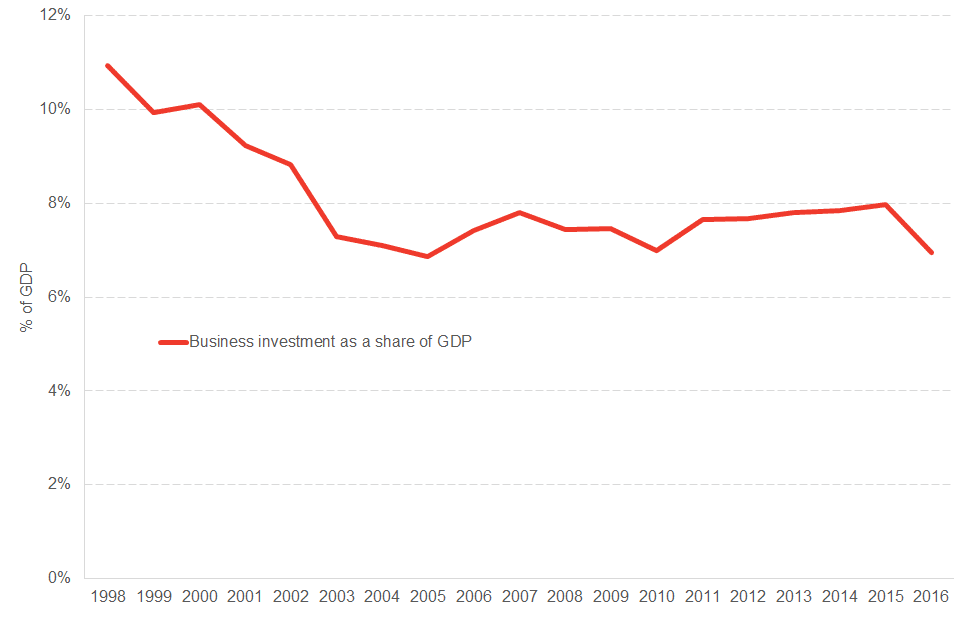

It would also be wrong however, to conclude that all of Scotland’s recent weak performance in business investment stems from Brexit.

As Chart 3 highlights, business investment in Scotland – as a share of GDP – has been falling for a sustained period of time.

Chart 4: Business investment as a share of GDP: 1998 to 2016

Source: Scottish Government, National Accounts

Boosting levels of business investment over the long-term must be key to tackling Scotland’s – and the UK’s – weak productivity performance.

Total investment in the UK by business, government and households is currently around 17%. This compares to 21% in Denmark, 22% in Finland, 23% in France, 19% in Germany and 25% in Sweden.

Whilst there is an important role for policymakers in encouraging investment, we should not overestimate their role or the impact one or two initiatives could have.

For example, take the planned Scottish National Investment Bank. Whilst there is no doubt a role for a public sector supported investment vehicle – to plug any gaps in finance not provided by the market – its scale and its potential to unlock new investment needs to be put in context. For example, the planned capitalisation of £350 million during the first two years of its operation compares to business investment of £20 billion over the period and Scottish Government capital spending of over £7 billion. It also needs to avoid crowding out existing finance already being provided.

At the same time, surveys repeatedly show that a key issue is not just the supply of finance, but generating increased levels of demand. The majority of firms that seek finance, secure at least some of the resources that they ask for.

Focussing attention on how to best support firms to have the ambition to invest might be less newsworthy as opening a ‘new’ bank, but it is no less important.

Establishing a business environment that supports growth and the start-up and scale-up of Scottish firms is key. It’s also about supporting ownership models and accounting structures which encourage long-term value creation rather than short-term quarterly profits.

It’s about ensuring that (large) firms respect payment timelines so that smaller firms are not having to worry constantly about cash-flow and can instead plan for investment.

And it’s about having a system of public intervention that makes it straightforward for business owners to identify the schemes best suited for them. One quick-win for the new National Investment Bank could be to provide a single transparent gateway through which investment opportunities could be accessed. At the moment, businesses face a complex web of possible funding sources from banks, venture capital, angel investments, peer-to-peer leading, the British Business Bank, the Green Investment Bank, and the Scottish Investment Bank (and its components – the Scottish Co-investment fund, the Scottish Venture fund, the Scottish Loan fund and the Renewable Investment fund).

But even then, public intervention can only do so much. Ultimately the onus is on businesses themselves to invest in their own growth. Waiting for certainty in the world economy or the next big policy initiative is unlikely to pay dividends.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.