It is 20 years since the devolved Scottish Parliament was established.

In many ways, the Scottish economy has been greatly transformed over that period.

What the next 20 years will hold is obviously uncertain. But with Brexit, the possibility of IndyRef2 and major structural shifts in our economy guaranteed, it is clearly going to be a period of further upheaval.

Economic and fiscal performance over the past 20 years

The first eight years of the parliament, from 1999 to 2007, were characterised by a strongly performing economy (in Scotland and the UK), and a growing Holyrood budget.

But in 2008, the global financial crisis tipped Scotland into a sharp and damaging recession.

What has been particularly challenging has been the fragility of the subsequent recovery – not just in Scotland but across advanced economies.

On top of this, the oil price shock of 2015 had a particularly negative effect on Scotland by dampening growth just when confidence was returning. A year later, in June 2016, the EU Referendum ushered in a renewed period of uncertainty.

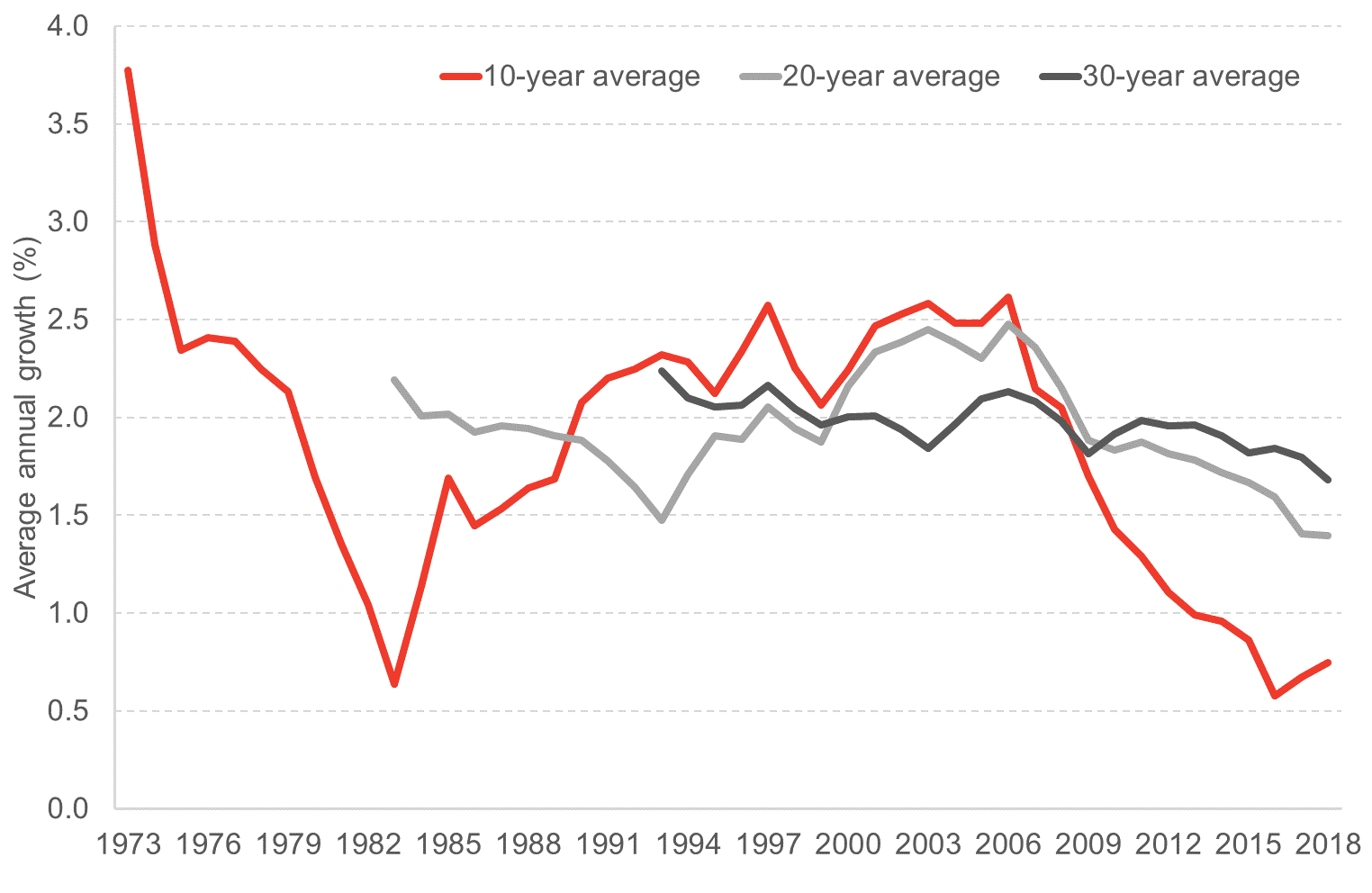

Scotland’s long-term growth rate is now well below trend. Chart 1.

Chart 1: Average GDP growth rates, Scotland, 1973 – 2018

The one bright spot has been the labour market, with employment at near record levels.

But unpicking the data reveals some concerns.

Whilst participation rates have risen sharply, a combination of weak wage growth, cuts to in-work benefits and fewer hours worked means that for many households, employment is no longer the route into a secure economic future it once was.

How has the Scottish Economy and Labour Market changed?

Much of Scotland’s long-term improvement in employment, unemployment and inactivity rates has been as a result of a sustained and significant uplift in female labour market participation.

The employment rate for women was 64% in 1999, now it is 73%.

Our labour market is also getting older – with a 40% increase in the number of people employed who are over 50 in the last 15 years.

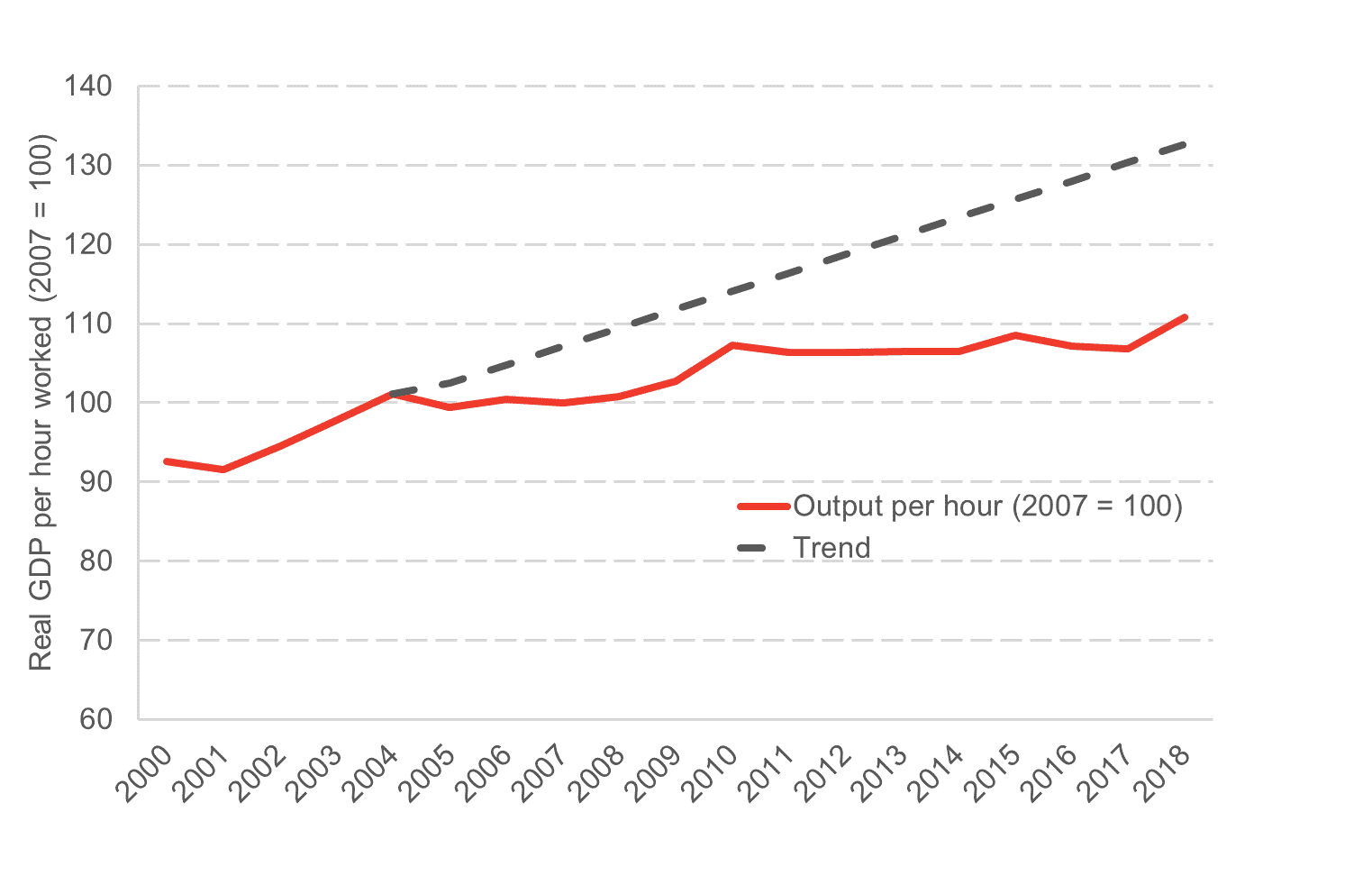

With relatively weak growth in the wider economy, but a strongly performing labour market, this has had consequences for Scotland’s productivity performance. Chart 2.

Chart 2: Scottish labour productivity & trend, 2000 – 2018

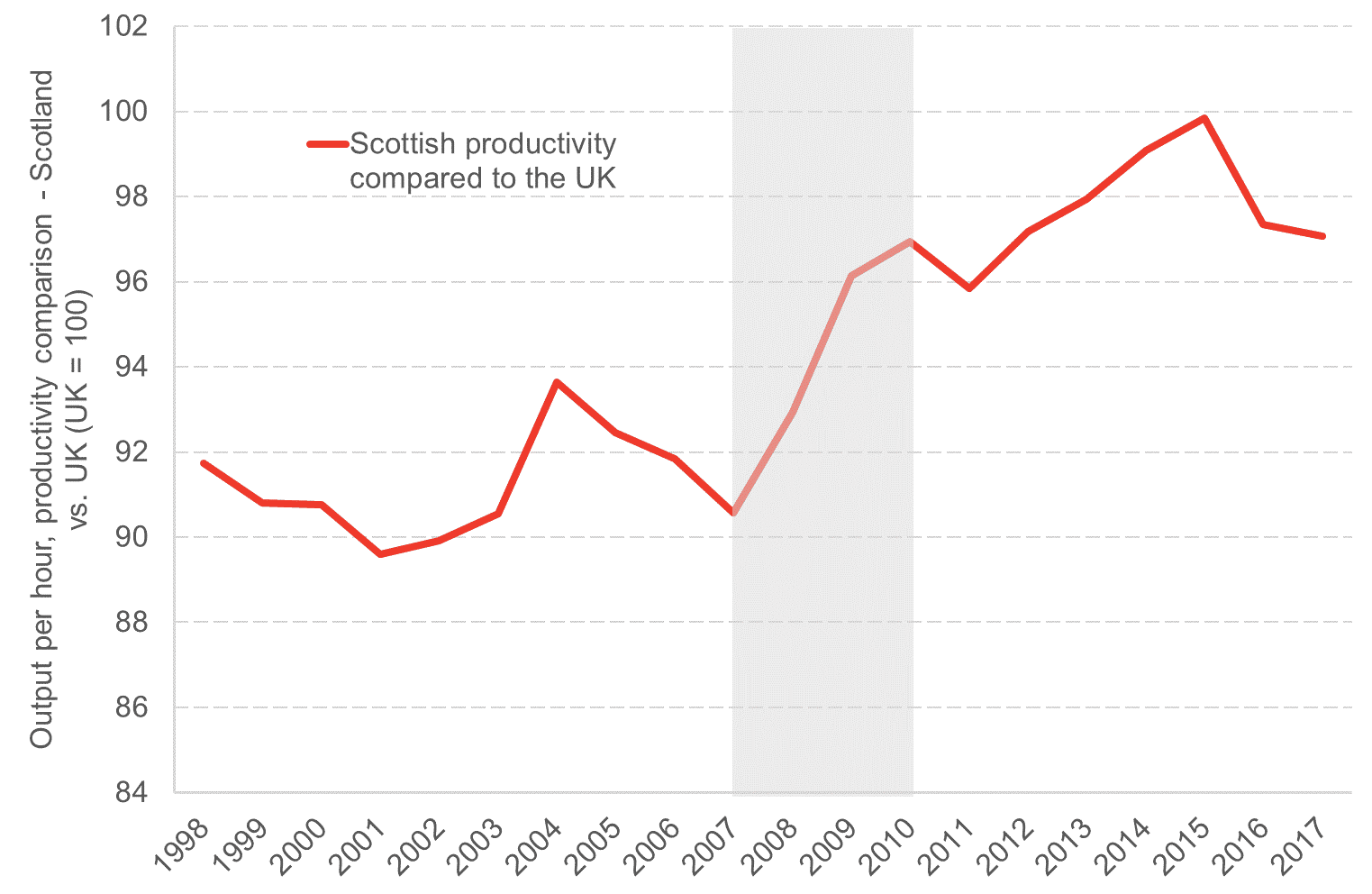

Scotland has however, ‘caught-up’ with the UK. Back in 1999, Scotland’s labour productivity was 91% of the UK’s. In 2017 it was 97%. Chart 3.

Chart 3: Scottish vs. UK labour productivity, 1998 – 2017

Source: Scottish Government, FAI calculations

Unpicking this reveals some interesting trends that unfortunately increasingly get ignored. In particular, Scotland’s relative improvement in productivity vis-à-vis the UK as a whole can largely be explained by changes in hours worked rather than a sustained uplift in relative economic efficiency.

As a result, people in Scotland might be relatively ‘more productive’ but this has been eroded by other means, including weaker growth in working hours.

A key driver of the growth in the number of people in work in Scotland has been the turnaround in Scotland’s population.

The population of Scotland has increased significantly since the turn of the century, reversing the decline since the 1970s to be at the highest level ever.

This increase has been driven by migration, both from the EU Accession countries and the rest of the UK. In general, natural change (i.e. births minus deaths) is negative, and therefore any population growth comes from migration.

So how much has devolution changed Scotland’s economic fortunes?

Answering such a question easily is clearly fraught with difficulties, given the lack of a counterfactual and the significant wider structural change that has taken place over this time.

Scotland continues to remain the wealthiest part of the UK outside of London and has had notable successes in areas such as renewable energy and attracting international investment.

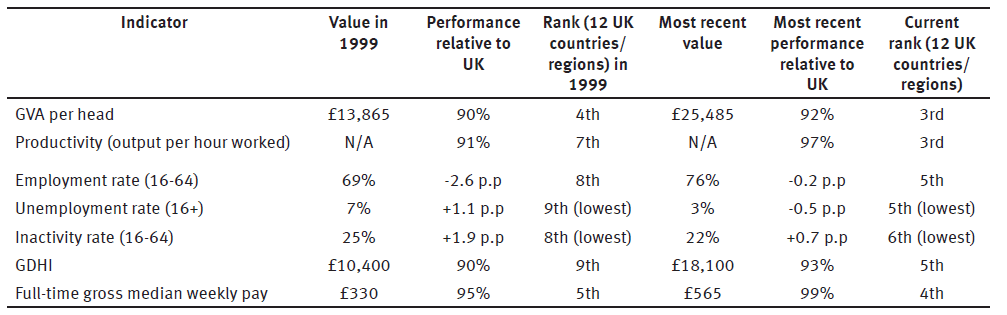

On a number of key macroeconomic indicators, Scotland has improved its relative position within the UK – both in terms of comparisons to the UK as a whole and to the other devolved nations and English regions. This includes on productivity and most labour market measures. Table 1.

Table 1: Economic indicators, 1999 – today

Source: ONS

Future economic and fiscal challenges

What is the next 20 years likely to hold?

Of course, the immediate change on the horizon is Brexit. And for policymakers at Holyrood this will mean not only dealing with the implications for the economy and society, but handling potentially significant legislative and fiscal changes.

The fallout from the ‘Great Recession’ and fiscal austerity have illustrated that – in many key areas – the major macroeconomic and fiscal policy levers remain at Westminster. But many of Scotland’s long-term challenges lie within devolved powers.

We highlight three – demographic change; climate change; inequalities and well-being.

Tackling Scotland’s unequal economy arguably remains the biggest challenge.

Some of this reflects the long-term nature of many of the interventions that we know will make a difference (e.g. in education).

But there is also a question about how bold and truly transformational the proposals being put forward are – by all political parties – particularly if Scotland is to meet its objectives in areas such as reducing child poverty.

For example, despite it being nearly five years since the Scottish Government launched ‘inclusive growth’ as its key policy agenda, the Poverty and Inequality Commission have raised concerns that the Scottish Government has not been sufficiently clear about what it means by inclusive growth, concluding that “inclusive growth appears to be more of a concept than something which results in a tangible outcome”.

Conclusion

The next 20 years are likely to see economic change at least as significant as the past 20 years, as well as further change to the constitutional settlement.

If Scotland is to meet the challenges of the next decade and beyond – and take advantage of the undoubted opportunities that will arise – it is likely to require a much bolder economic policy agenda.

Read our full discussion on 20 years of Devolution and the rest of our latest commentary here: https://www.sbs.strath.ac.uk/download/fraser/201906/20190626-Commentary.pdf

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.