Economic Futures, a project funded by the Scottish Funding Council, aims to engage with undergraduate economics students, graduates and early career academics, across Scotland to provide an eco-system for applied economic analysis. Find out more here.

The 2020 Economic Futures Essay Competition was open to all Scottish students registered at a Scottish University studying Economics or an economics-related subject. Students were invited to write an essay on an Economics topic related to COVID-19. The competition was fierce and we had almost 100 entries, all of a very high standard.

The winner’s of the competition were:

1st: Catherine Bouchard, University of Glasgow

2nd: Maciej Zielinski, University of Glasgow

3rd: Lori McCluskey: University of Dundee

4th: Leanne Wilson: Glasgow Caledonian University

You can read the final 10 essays here.

In the next week we will be featuring the top 4 essays as articles in collaboration with our latest Economic Commentary, today we feature ‘How reliant are UK universities on Tuition Fees and How will they adapt in a post-pandemic world?’, written by Lori McCluskey of the University of Dundee.

Introduction

A magnet for international students, UK universities rely heavily on international tuition fees to maintain financial stability. However, the COVID-19 pandemic is putting this stability at risk, with the number of students coming to the UK set to drop. Britain has the second highest number of international students in the world yet it is unclear how many will matriculate come Autumn 2020 (Johnson, 2020).

This essay aims to explain how reliant UK universities are on tuition fees and what the potential impact going forward may be if universities suffer drops in student numbers and fee income – mainly from international students – as a result of the pandemic. This will be explained by identifying universities’ income sources and identifying which countries the majority of international students come from.

Sources of Income and the Role of Fees

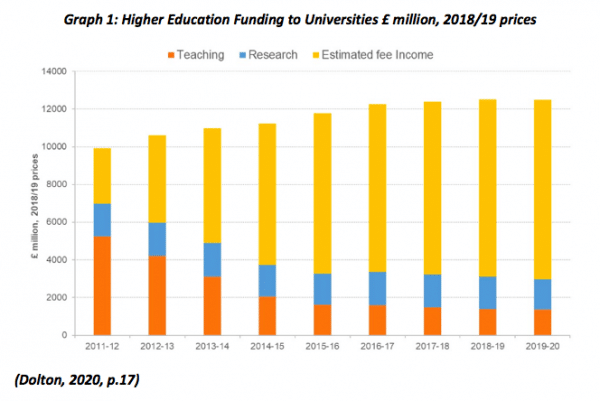

Evidence has shown that fees play an integral part in university funding and have become increasingly important over the past decade (Economics Observatory, 2020). The UK is home to 141 universities and the majority earn approximately 75% of income through fees (Dolton, 2020, p.3). As recently as 2011-12, fee income made up a relatively small proportion of university funding, with around half of funding coming from the UK government. However, by 2019-20, this structure has changed dramatically, with around a quarter of funding coming from government and the majority now coming directly from fees (Economics Observatory, 2020). The graph below illustrates this striking change:

Chart 1: Higher Education Funding to Universities £ million, 2018/19 prices

In 2018-19, the total income from international fees to universities was £7 billion, equating to around 17.3% of funding as a whole. However, some universities are much more reliant on this income stream than others (Dolton, 2020, p.4). Scottish universities in particular are in a vulnerable position as they have had to become very dependent on receiving international fees as a source of income, since Scottish students do not pay fees. Their main sources of income are: income from the Scottish Funding Council (to cover fees for Scottish and EU students), fees from English, Welsh and Northern Irish students (up to £9,000 per year) and international fees, which are uncapped, and can total up to £30,000 per year. Additionally, older universities in Scotland (typically established pre-1990) tend to have more international students than newer universities, therefore they are more reliant on this income stream (McIvor, 2020).

This £7 billion is extremely important to universities as it covers losses which arise through research and contributes to the delivery of costly subjects, such as lab-based subjects and those which are crucial to the UK’s creative sectors. For example, 56% of students at University of the Arts London (ranked second worldwide for art and design in the QS World University Rankings) are international students (Johnson, 2020), which exemplifies the importance of international fees and how they help sustain the UK’s world-leading university system.

Which countries do the majority of international students come from?

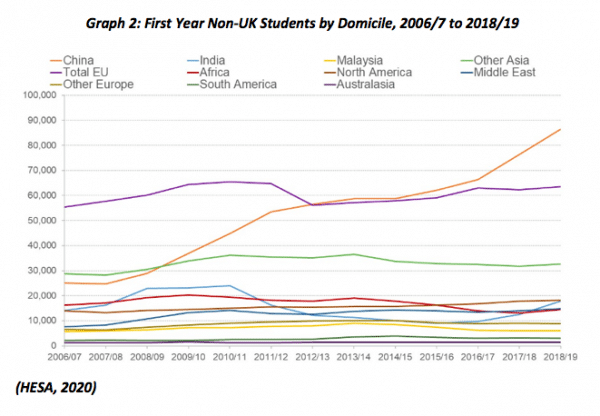

As is now apparent, universities depend heavily on international fees but evidence shows that from 2006/07-2018/19, the number of new students coming from China to the UK increased dramatically (from 25,000 to around 90,000 by 2019), while numbers from other countries remained constant (Economics Observatory). The graph below illustrates this scenario:

Chart 2: First Year Non-UK Students by Domicile, 2006/7 to 2018/19

This demonstrates just how dependent universities are on Chinese students and therefore any major disruption, such as the pandemic, that hinders Chinese students from enrolling, puts universities in a vulnerable and potentially unstable position.

Chinese students make up the largest percentage of international students in the UK and in 2019, 115,014 study visas were issued to Chinese students, contributing to 45% of the total number issued (British Council, 2020). However, due to the pandemic, English language examinations – which prospective students must undertake to be admitted to UK universities – have been cancelled in China, deterring students from enrolling.

If admissions from China (as well as Hong Kong, Macau, South Korea and Japan) were to fall by only 10%, universities could be facing fee losses of more than £200 million (Rodionova, 2020). In 2020, it cost international students between approximately £10,000 and £26,000 per year to study in the UK, depending on degree type and the university they attended. However, degrees in medicine can cost up to around £58,600 annually (THE, 2020).

A survey of around 11,000 Chinese students contemplating studying in the UK – carried out between 27th March and 3rd April 2020 – showed that 39% were undecided on whether or not to come, in light of the pandemic, due to worries over health, personal safety and finances (British Council, 2020). This uncertainty makes it difficult for universities to know what plans they must put in place going forward and how much of a funding gap they face if they lose out on receiving these high fees.

What happens next?

As it is difficult to predict how severe the problem will be, many universities are preparing for worst-case scenarios: a drop of 75% in international students and 20% in domestic students this September. This would put universities in deep financial trouble, with predictions that every UK university would likely be insolvent, excluding Oxford and Cambridge (Economics Observatory, 2020). Warnings have also been given regarding the gaps in student intake for 2020 across universities, meaning that some university populations may grow while others shrink and may no longer be financially operable (Coughlan, 2020).

Regarding the details of these potential declines in student numbers, the most uncertainty lies within the number of first-year students choosing to start university. School leaver results are being awarded using students’ predicted grades, however, this could mean that more students fulfil conditional offers due to over-estimation of grades by teachers, according to NIESR. Still, this does not mean that there will be more first-years starting university, as a higher proportion than normal may choose to defer. Alternatively, it appears that those moving into second or third/final year will likely continue their studies, regardless of which format this takes (Dolton, 2020, p.20).

To cut costs and finance their operations with less students and income, universities are considering various options such as: hiring less staff, redundancies and even shutting-down departments or ceasing to offer degree courses which are deemed low-quality or low value for money. Additionally, London Economics report 2020 estimates up to 30,000 jobs may be lost within the UK’s higher education sector (Dolton, 2020, p.24). There are hopes that these measures will not be needed and that these job loss estimates do not transpire, if worst case scenarios do not occur and demand from countries such as China and India is still there come Autumn 2021 (Dolton, 2020, p.24-25).

As for government support, Johnson states that without it, maintaining the UK’s prestigious higher education system (with three universities in the world’s top ten and thirty-one in the world’s top two-hundred) would be unfeasible (Johnson, 2020). Furthermore, Convenor of Universities Scotland, Professor Andrea Nolan, warned that financial aid from both Scottish and UK governments is essential to maintain high educational standards and support Scottish universities in the long-run (McIvor, 2020). Universities UK asked the UK government for £2.2 billion to aid immediate funding for research projects, which was denied. Instead, funding for research will be increased by just £100 million and an advance on income from undergraduate fees from the Student Loan company of £2.6 billion will be allowed, constituting approximately a 10% loan of fee income to universities. In the short-run, this will save some universities, however, many may face future financial problems when these loans must be paid back (Economics Observatory, 2020).

On a more positive note, the pandemic has forced universities to quickly implement online and distance learning, which was not widely utilised before. This is arguably more accessible to middle-income families who may struggle to send their children abroad to embark on lengthy degree programmes with high fees. Therefore, the pandemic may have sparked new opportunity for universities. Conventional multi-year degree courses will likely continue to be demanded, especially by more-privileged groups, however, the development of online learning may move UK universities forward and allow them to draw students from a wider spectrum of society (Johnson, 2020).

Conclusion

It is evident that tuition fees have become extremely important to UK universities, providing a main source of funding for many. International fees in particular are crucial as they are typically higher than domestic fees, with those from Chinese students contributing to the majority of international fees received.

With COVID-19 hindering students from coming to the UK, universities face an unstable future, characterised by reduced student numbers and income, with job losses, hiring freezes and degree programme closures likely to occur as a result, if worst-case scenarios ensue.

There are hopes that this is a temporary slump and demand from international students will be restored come Autumn 2021, along with perhaps more accessible online learning opportunities. However, for the time being it appears to be a matter of wait and see, putting the UK’s excellent higher education reputation at risk. Whatever happens this coming Autumn may be a ‘make or break’ moment.

You can read the full essay in PDF format here, and also read the other top 9 essays on the Economic Futures website.

Authors

Lori McCluskey

Lori is a masters student at The University of Dundee