Employment support in Scotland is a relative patchwork of schemes with responsibility seemingly shared between the Scottish, UK and local government. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, there will no doubt be more people needing support to find new employment and this is an issue that we expect to be talked about more and more as we move towards the Scottish election. Here is what we have pieced together in a bid to understand the current landscape.

According to UK Government Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses (PESA) country regional analysis, £215 million was spent in Scotland on employment support in 2019-20. This captures spending from all levels of government: UK, Scottish and local.

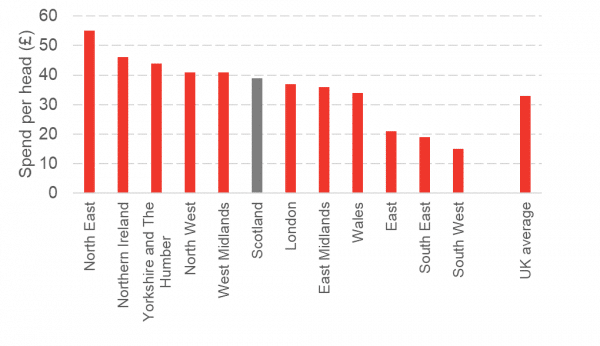

By UK country, on a per head basis, spending is higher in Scotland than the UK average but below Northern Ireland where the highest per-head spending is found. Chart 1 shows spending per head across UK countries and English regions.

Chart 1 Per head spending on ‘employment policies’ across the UK

Because spending is spread across various different parts of the public sector, and delivered by a range of public, private and third sector organisations, it can be quite difficult to keep track of the various programmes and to identify who is responsible for what. Given the 2021 Scottish Election just around the corner, this article focuses on the programmes and funds that are part of Scottish Government policy.

Pre and post Smith Commission

Pre-Smith commission, training for employment was a shared responsibility between the UK and Scottish Government, but ‘employment services’ (often referred to as employability) were reserved (although various schemes have existed at the local government level for many years).

The Smith Commission recommended devolution of “employment programmes currently contracted by DWP”. From the 1st April 2017, Scotland took responsibility for support previously provided by DWP for the long term unemployed (the work programme) and those with a disability (work choices).

This pre-devolution separation of ‘training for employment’ and ‘employment services’ seems to have carried over into the structures in the Scottish Government, with employability part of the Economy, Fair Work and Culture directorate and the Education directorate retaining responsibility for Skills Development Scotland and ‘employment and training intervention’.[i]

The rest of this brief first focuses on the main employability services that were devolved following the Smith Commission and then looks to the wider landscape.

Fair Start Scotland

Fair Start Scotland became the replacement for the previous DWP employment programmes. It is delivered in 9 areas across the country by third party (mainly private sector) organisations who bid for the contracts. People are either referred via the Jobcentre Plus, a third-party organisation involved with the service, or people can refer themselves.

The most recent figures for the first two years of operation shows that around 30,000 people have so far joined Fair Start Scotland with around 9,500 starting a job[ii].

The necessity of provision of lengthy pre-employment support for some means that this is not a complete picture of impact (and Covid-19 may also affect the numbers who ultimately transition into work). However, there were concerns at the outset that those furthest away from the labour market would not do well in this system geared around ‘payment by results’ and that the specialist, third sector, providers of support for people with more complex support needs had not been able to compete for contracts[iii].

It appears the Scottish Government originally considered moving employability support for disabled people over to Skills Development Scotland[iv]. At some point, this position changed and their employability support became part of Fair Start Scotland. Whilst most people have be long term unemployed (for at least 2 years) to join Fair Start Scotland, this condition does not apply to people with a disability or long-term health condition. From April 2019 to March 2020, 44% of the Fair Start Scotland population were classified as having a disability or a long-term limiting health condition[v]. Outcomes for this group of people will be a key indicator of success of Fair Start Scotland and whether the concerns expressed at the outset were founded.

The contracts were originally to run to March 2021, but have since been extended for two years till March 2023 which appears to be in response to the pandemic[vi].

The wider landscape and new Covid-19 schemes

There are a range of other employability programmes that the Scottish Government support. Some of the other schemes currently in existence include:

Our Future Now: Works with charities across Scotland to support young people into education, employment and training.

Employability Fund: A Skills Development Scotland fund that woks with local employability partners. Focused on addressing the needs of specific local areas.

Community Jobs Scotland: A scheme delivered by the Scottish Council for Voluntary organisations (SCVO) that works with voluntary sector employers to help young people who are most disadvantaged in the labour market (including care leavers, those with disabilities and those with convictions) into jobs.

Discovering Your Potential: Provides flexible and intensive support for young care leavers

Parental Employability Support Fund: Originally part of the Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan, this is designed to give support to parents both in and out of work to increase their income from paid employment.

Partnership Action for Continuing Employment (PACE): Long established service, led by Skills Development Scotland, to respond to redundancy situations. It is a national partnership, and includes Jobcentre Plus, local authorities, Citizens Advice and colleges and training providers. Delivered by local PACE teams.

Understanding how this patchwork of support fits together is not simple to understand – a view shared by the Scottish Government. In 2018, the Scottish Government published a plan to make the system more ‘joined up and straightforward’[vii].

Progress was ongoing as Covid-19 struck, which appears to have led to the decision to delay some of the changes envisaged although the commitment around alignment and integration remains[viii].

New schemes have come onto the scene to respond to Covid-19. A new Scottish Government policy the Young Person’s Guarantee seeks to provide job, placement, training of volunteering opportunities for every 16-24-year-old in Scotland. There is also the new UK Government Kickstart scheme that will operate across the UK. This scheme funds employers to provide six-month work placements for 16–24 year olds who are claiming Universal Credit. However, the UK Government’s Restart scheme, which gives Universal Credit claimants enhanced support to find jobs in their local area won’t apply in Scotland.

Where next?

Navigating all this is a complex business, and with this much going on, even in normal times it would be hard to be sure what is working well, what isn’t, and why. With Covid-19, the employability services operating in Scotland will arguably face their biggest test. Integration across all levels of government in delivering support feels more crucial than ever.

We still do not know the implications of the Covid-19 pandemic on the labour market, and it will not be until much of the UK Government support schemes, such as furlough, are removed that we will get the full picture.

As we mentioned in our podcast last week, this makes policy development at this election difficult but discussion and debate around what might be needed is still valuable. However, this feels like one of the more cluttered policy landscapes in Scotland. New ideas are no doubt needed due to the scale of the challenge facing the labour market. Hopefully this can be done without making things too much more complicated for people who need support from the system.

[i] Scottish Parliament Information Centre (2015) ‘The Smith Commission Report – overview’ https://archive2021.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefingsAndFactsheets/S4/SB_15-03_The_Smith_Commission_Report-Overview.pdf

[ii] Fair Start Scotland reporting: http://www.employabilityinscotland.com/find-support/about-fair-start-scotland/-fair-start-scotland-reporting/

[iii] SCVO (2017) ‘Fair Start Scotland: contracts, commissioning and the marginalisation of the third sector and those we support’: https://scvo.scot/p/16239/2017/10/04/fair-start-scotland-contracts-commissioning-and-the-marginalisation-of-the-third-sector-and-those-we-support

[iv] Scottish Government (2016) ‘A new future for employability support in Scotland’ https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/corporate-report/2016/03/creating-fairer-scotland-new-future-employability-support-scotland/documents/00498123-pdf/00498123-pdf/govscot%3Adocument/00498123.pdf

[v] Scottish Government (2020) ‘Fair Start Scotland Evaluation Report 3: Overview of year two’ https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/research-and-analysis/2020/11/fair-start-scotland-evaluation-report-3-overview-year-two/documents/fair-start-scotland-evaluation-report-3-overview-year-2-november-2020/fair-start-scotland-evaluation-report-3-overview-year-2-november-2020/govscot%3Adocument/fair-start-scotland-evaluation-report-3-overview-year-2-november-2020.pdf?forceDownload=true

[vi] Notice of extension of Fair Start Scotland http://www.employabilityinscotland.com/find-support/about-fair-start-scotland/-extension-of-fss-services/

[vii] Scottish Government (2018) ‘No One Left Behind: next steps for employability support in Scotland’ https://www.gov.scot/publications/one-left-behind-next-steps-integration-alignment-employability-support-scotland/pages/10/

[viii] Scottish Government (2020) ‘Not One Left Behind: delivery plan’ https://www.gov.scot/publications/no-one-left-behind-delivery-plan/pages/7/

Authors

Emma is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute