All of us are likely to need care at some point in our lives. How this care is paid for, accessed and provided is a complex matter, as adult social care in Scotland is delivered by a network of organisations, and policy decisions lie at different levels of government. This briefing outlines how the system works overall, and considers potentially significant changes proposed ahead of this election.

The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic has placed the system under enormous strain and is likely to create increased demand on some parts of the system in future. Furthermore, the pandemic has highlighted the contribution made by unpaid carers and low paid care workers. This, along with an ageing population with ever more complex care needs, means that social care reform might be one of the major policy issues for all parties to grapple with at the 2021 election and beyond.

What is adult social care?

Adult social care is often thought of as referring solely to elderly people living in care homes. In reality, the social care system delivers a wide range of support for a variety of reasons for adults of all ages. Support delivered by the social care system can include residential care placements, personal care at home or in a care home (for example, help washing, dressing and cooking), support managing finances and other help that enables people with a disability to live as independently as possible, contribute to society and maintain their human rights.

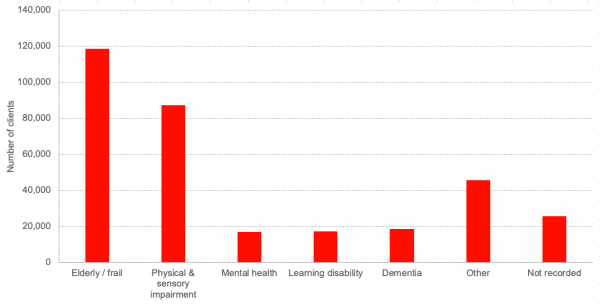

Around 246,000 people (1 in 20 of the population) received support from Scotland’s social care system in 2018/19[i]. Eligibility for social care support is determined by a needs assessment and is not dependent on age or medical condition. Social care users fall into a variety of “client groups”, as shown below (note that users can fall into more than one category).

Chart 1: Social care client groups in Scotland, 2018/19

Source: Public Health Scotland[i]

Whilst age is not a qualifying factor, the majority of social care users are over 65[i]. The number of people aged 75 and over in Scotland is projected to increase by around 70% over the 25 years from 2018 to 2043[ii]. As the population ages, the prevalence of long-term health conditions is likely to increase, creating greater demand on the social care system with proportionately fewer working age adults to fund it. This is part of the reason why the future of social care is becoming an increasingly important policy issue.

One of the other key issues is around the funding of the system. In 2018/19, £3.8billion was spent on formal adult social care in Scotland[iii]. But the adult social care in Scotland is funded by local authorities who have seen pressures on their budgets rise over the last decade or so. Whilst many aspects of adult social care are protected, there has been pressure on non-statutory services. In our work looking at the social care system for adults with learning disabilities, both people with learning disabilities and those working in Health and Social Care Partnerships reported clearly that (in some parts of Scotland at least) services that helped people participate actively in society, find work, and live independently have been cut back in recent years[iv].

The current adult social care system

The policy landscape is devolved in Scotland, with legislation passed in the Scottish Parliament determining the frameworks and standards that apply nationally. However, responsibility for delivering the social care system sits at a local level. This has the advantage of local decision making when it comes to commissioning services but can result in inconsistencies in what is available between different areas of the country.

In 31 of Scotland’s 32 local authority areas, health and social care services are commissioned by Integrated Joint Boards (IJBs) following the integration of health and social care (see below). Local Health and Social Care Partnerships (HSCPs) carry out the commissioning as the delivery arm of IJBs.

However, local authorities have retained responsibility for procuring and contracting care from providers, which is different from commissioning. This means that the procurement process is not necessarily distinct from those of other council services.

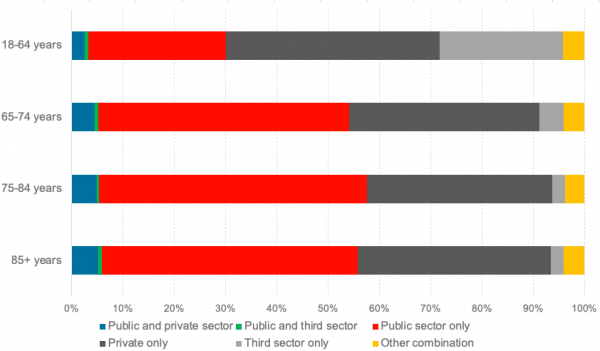

Adult social care services are delivered by a mixture of local authorities, private and third sector providers. Local authorities are procuring an increasing share of services from private and third sector providers, with 47% of home care clients (ie. services delivered in an individual’s own home) receiving services run by public sector bodies, compared with 71% in 2008[v].

Chart 2 shows the combination of providers by age for home care, which covers services such as help washing, dressing or cooking delivered in a person’s own home. The chart shows how differently the social care system operates for different users, as the private and, in particular, the third sector plays a far more significant role in providing home care services to those of working age.

Chart 2: Service providers of home care by age, 2018/19

Source: Public Health Scotland[i]

The contribution of unpaid carers is also significant. The exact number of unpaid carers in Scotland is not known but Scottish Government research in 2015[vi] put the figure at around 790,000. Research in 2015 by Sheffield University[vii] estimates that the care provided by unpaid carers in Scotland is worth £10.8billion per annum.

Adult social care is funded by a mixture of taxation and user charges, but in many circumstances, care is not provided by the state and is privately funded. In order to access the system, an individual must have a needs assessment completed by a professional, such as a social worker or occupational therapist. If a person’s needs meet set eligibility criteria, the next consideration is their means.

Residential care must be paid for by individuals whose assets are valued above the Higher Capital Limit of £28,500, known as self-funders. The cost of community care, which covers services such as learning disability day centres and support that helps people with disabilities live more independently, can vary by region and an individual’s circumstances.

Uniquely in the UK, the cost of personal care is free for over 65s across Scotland. This covers services like personal hygiene, food preparation and administering medical treatment, but not housework or ancillary services. Personal care can be delivered in an individual’s own home or in a residential care home. Local authorities make a contribution to self-funders’ residential care fees to cover the cost of personal care (£193.50 per week) and nursing care (£87.10 per week)[viii].

How the policy landscape has changed

2 major changes in the way that adult social care is delivered have been passed by the Scottish Parliament in the last decade.

Integration of health and social care

Legislation passed in 2014[ix] created 31 integration authorities across Scotland that are responsible for commissioning both health and social care services. The rationale behind this was to create joined up services with a greater emphasis on preventative care so that individual needs can be met by a single system.

However, whilst legislation has created an integrated authority at the top, our recent research found that there is still some way to go before health and social care teams are integrated on the ground.

A 2018 Audit Scotland report[x] also found that progress towards integration delivering the hoped-for benefits has some way to go. It concluded that integration had been held back by financial planning that is insufficiently long-term or outcomes focused, as well as several “significant barriers” such as a lack of collaborative leadership, high staff turnover in leadership teams and unwillingness to share data.

Self-directed support

The Scottish Parliament legislated for the nationwide roll out of self-directed support (SDS) in 2013[xi]. This gives social care users flexibility and choice over how to use their personal budget, with the aim of enabling service users to tailor their support and care in a way that meets their individual needs.

Social care users can choose between four options over how to spend their budget:

- Direct payment to the individual, who then arranges their support.

- The individual chooses and directs the support, which is then arranged by a provider or local authority.

- The local authority commissions and arranges support.

- A mixture of the above options for different types of support.

As with integration, the theoretical benefits of SDS are yet to be realised in full. A 2017 progress report by Audit Scotland[xii] found “examples of positive progress” but “no evidence that authorities have yet made the transformation required to fully implement the SDS strategy”.

Perhaps further evidence of this is that of those who chose an SDS option, the vast majority (81%) chose option 3[i], which gives local authorities the responsibility of arranging an individual’s services, rather than choosing an option that gives users more control over their care and support.

Social care reform and a National Care Service

Across the UK, reforming adult social care so that it meets the long-term challenges it is facing has been a longstanding and unresolved issue for governments to contend with. In Scotland, the recent Independent Review of Adult Social Care[iii], chaired by Derek Feeley, proposed a National Care Service, with legal accountability for adult social care moving to Scottish Government ministers, rather than local authorities.

We await full details of how the parties will respond to this in the upcoming manifestos. But a National Care Service could mean many things, depending on the details of how it is established.

The Independent Review made the following recommendations.

A structural reorganisation of statutory responsibilities that gives accountability for the social care system to government ministers is the ‘headline’ change proposed. Some elements of the system might be organised on a national level, such as national collective pay settlements for care workers, national infrastructure on sharing best practice, and social care in prisons, or for those with complex or specialists needs.

Local IJBs would continue operation and receive a bolstered responsibility to commission and deliver services and contracts directly. The hoped-for benefit would be to speed up the integration of health and social care. Budgets would be set and distributed by the Scottish Government, rather than local authorities and NHS Boards.

The report makes clear that establishing a National Care Service is not the same as nationalisation. Rather than taking care providers into public ownership, the expectation is that independent and voluntary providers would continue to deliver services. The review does, however, suggest changes in procurement practices to place more responsibility on providers to meet ethical standards or reinvest profits into improving care quality, for example. A new approach to commissioning, in which services are developed by commissioners, providers and those with lived experience (such as Disabled Persons’ Organisations) working collaboratively, is also recommended.

The Independent Review also suggests some models of care that should be explored more widely. Shared Lives, which we covered in our recent research, Home Share and extra care housing are examples of care models that have had localised success which has not been replicated nationally. The review also highlights the need for more technology enabled care and early intervention.

Even if a National Care Service is established, the question of how to fund adult social care in the long-term still remains. The Independent Review estimates that its recommendations amount to an additional £660million (0.4% of Scottish GDP) per annum and the review does set out some options for policy makers to consider to raise additional revenue:

- Introduction of mandatory social insurance;

- Changes to existing devolved taxes to raise additional revenue;

- Introduction of a new local tax;

- Seeking devolved powers for a new national devolved tax in Scotland;

- Seeking devolution of existing reserved taxes to raise additional revenue.

Ultimately, the long-term trends that are driving increased demand for adult social care, combined with proportionately fewer adults of working age to fund it, create a challenge for society that will span more than one parliamentary term. The 2021 election offers parties a chance to set out ideas of how to meet that challenge.

[i] Social Care Insights, Public Health Scotland (2018/19)

https://scotland.shinyapps.io/phs-social-care-people-supported-201819/

[ii] Projected population of Scotland (2018-based), National Records of Scotland (2020)

https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/population/population-projections/population-projections-scotland/2018-based

[iii] Independent Review of Adult Social Care, Scottish Government (2021)

https://www.gov.scot/publications/independent-review-adult-social-care-scotland/

[iv] Evidence on Scotland’s adult social care system for people with learning disabilities, Fraser of Allander Institute (2021)

https://fraserofallander.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/2021-02-FAI-adult-social-care-learning-disabilities-Feb-21.pdf

[v] Social care services Scotland, Scottish Government (2017)

https://www.gov.scot/publications/social-care-services-scotland-2017/pages/3/

[vi] Scotland’s carers, Scottish Government (2015)

https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-carers/

[vii] Valuing Carers, Carers UK and Sheffield University (2015)

https://www.carersuk.org/news-and-campaigns/news/scotland-s-carers-save-economy-10-8-billion-a-year-the-cost-of-a-second-nhs

[viii] More help with free personal and nursing care, Scottish Government (2021)

https://www.gov.scot/news/more-help-with-free-personal-and-nursing-care/

[ix]Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2014/9/contents/enacted

[x] Health and social care integration progress report, Audit Scotland (2018)

https://www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/uploads/docs/report/2018/nr_181115_health_socialcare_update.pdf

[xi] Social Care (Self-directed Support) (Scotland) Act 2013

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2013/1/contents/enacted

[xii] Self-directed support progress report, Audit Scotland (2017)

https://www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/uploads/docs/report/2019/ir_191217_self_directed_support.pdf

Authors

Knowledge Exchange Associate at the Fraser of Allander Institute

Emma is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute