Early today, the Deputy First Minister announced the Scottish Government’s draft budget. This is (hopefully!) the last of many fiscal statements this year affecting Scotland.

As well as the draft budget, today also saw a new set of forecasts for the Scottish economy and public finances released by the Scottish Fiscal Commission. These take account of decisions made by the UK Government at the Autumn Statement, and also new announcements made by the Scottish Government today.

There is a lot to digest, and we are here to help. We will return in the New Year with more in-depth analysis but here we provide a summary of the key announcements on resource budget for 2023-24.

Economic position

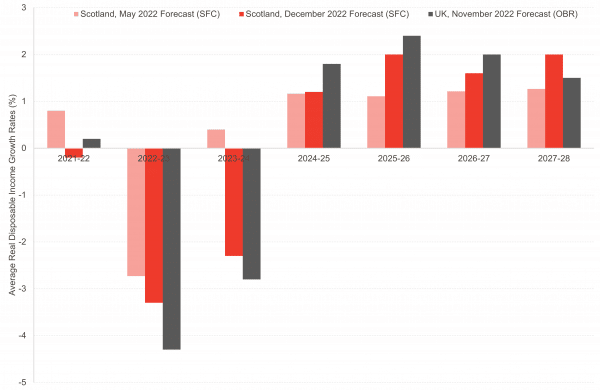

Originally, the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) predicted a return to pre-pandemic GDP levels by Q3 2022. Of course, Q3 2022 had a series of misfortunes which caused a much more significant slowdown in the economy than could have been predicted back in May.

Now, facing a potentially long-running economic contraction, Scottish GDP is not expected to rebound to pre-pandemic levels until well into 2025. Growth is furthermore expected to move more slowly in Scotland than the UK average, as forecasted last month by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) (Chart 1).

The decline in GDP is due to drops in consumption, trade, and private investment over 2023-2024, which makes sense, given the high cost of living, higher interest rates, and ongoing trade difficulties due to the UK’s exit from the EU.

Chart 1: Real GDP growth rate forecasts, 2022-2027

Source: FAI analysis of OBR and SFC forecasts

The funding position

Table 1: Overview of resource funding position in 2023-24 (£m)

| Funding from UK Government | UK Autumn Statement Baseline* | 36,023 |

| Block grant adjustment for welfare | 4,360 | |

| Non-Barnett funding + non-tax BGAs | 1,226 | |

| Revenue raised by the Scottish Government | NDR income & other funding | 3,482 |

| Devolved taxes | 16,688 | |

| Other fiscal framework adjustments | Tax block grant adjustment | -16,642 |

| Reconciliations | 46 | |

| Borrowing | 41 | |

| Resource & capital borrowing costs | -232 | |

| Total resource funding available | 44,992 | |

| *Includes consequentials | ||

Source: FAI analysis of SFC figures

Change to funding from UK Government

As set out in our Budget report published earlier this week, the outlook for the Scottish Government off the back of the UK Government’s Autumn statement was flat in real terms for 2023/24. New consequentials will come through the block grant in 2023-24, a much better scenario than feared a few months ago.

Added on to this is the block grant adjustment for social security spend. This has increased since the Resource Spending Review as a result of uprating by higher than expected inflation and due to higher than expected caseload for Personal Independence Payment in England and Wales (a devolved benefit).

Additional revenue raised in this Budget

Alongside the resource block grant, the Scottish Government also raises money through a range of devolved taxes.

There are two key taxes where changes have been made today that alter the funding position: income tax and non-domestic rates.

Income tax

As widely expected, the Scottish Government have decided to freeze the Scottish basic, intermediate and higher rate thresholds in cash terms, and to reduce the threshold at which the top rate of tax becomes payable, from £150,000 to £125,140. Both these changes are in line with UK Government decisions made at the Autumn Statement.

The government have also announced an increase in LBTT paid on additional properties from 4% to 6% which the SFC suggest will generate an additional £34m in 2023/24.

The revenue impact of these decisions mean that the Scottish Government will raise an estimated £15.8bn in 2023-24 from income tax according to the SFC, bringing total revenue from devolved taxes (including Land and Buildings Transaction Tax and Scottish Landfill Tax) to £19.7bn.

As reported in our budget report, the main implication of the reduction in the top rate income tax threshold from £150,000 to £125,140 is the increase in the number of taxpayers paying the top rate of income tax, which we estimate is around 12,000 individuals.

In addition to this threshold change, the government have also announced increases in the top rates of income tax in Scotland, with 1p increases in both the additional and top rates of tax, to 42p and 47p, respectively.

Table 2: Scottish tax bands, rates, and changes

| 2022/23 | 2023/24 | Changes | |||

| Earned Income | Scottish Tax Rate | Earned Income | Scottish Tax Rate | ||

| Personal allowance* | £12,570 | £12,570 | Unchanged | ||

| Starter Rate | £12,571 – £14,732 | 19% | £12,571 – £14,732 | 19% | Unchanged |

| Basic Rate | £14733 – £25,688 | 20% | £14733 – £25,688 | 20% | Unchanged |

| Intermediate Rate | £25,686 – £43,662 | 21% | £25,686 – £43,662 | 21% | Unchanged |

| Higher Rate | £43,663 – £150,000 | 41% | £43,663 – £125,140 | 42% | Scottish Tax Rate increased by 1p in the £ |

| Top Rate | Over £150,000 | 46% | Over £125,140 | 47% | Threshold reduced from £150,000 to £125,140 Scottish Tax Rate increased by 1p in the £ |

*Level not under control of Scottish ministers. The personal allowance is reduced by £1 for every £2 earned between £100,000 and £125,000

The tax changes taken together are forecast to raise an additional £129 million in 2023/24. This is slightly different than the figure given by the Scottish Government of £553 million for Income Tax and Land and Building Transactions (LBTT) policy changes combined. The LBTT costing is only £34 million and the residual comes from a difference of opinion on whether or not the counterfactual (pre-policy change) should assume that the higher rate threshold should be raised by inflation or not. SFC assume it is not.

It is worth remembering that those in the higher rate tax threshold (let alone the top rate) are at the top-end of the earnings distribution. The current-cut off for the higher rate of income tax (£43,662) applies to individuals at the 90th percentile of the earnings distribution. That is, only 10% of earners fall into this rate. In terms of taxpayers (i.e. those over the personal allowance paying some non-zero income tax) 16% of taxpayers pay the higher rate. The average (median) taxpayer in Scotland has before-tax earnings of around £25,000.

Non-domestic rates

Revaluation of the non-domestic rates tax base means that this is not an ordinary year for non-domestic rates. Holding all else equal, a change in the size of the tax base usually means a corresponding change in the rate (or poundage) levied on the non-domestic properties, leaving the overall revenue raised unchanged. After that, an inflationary adjustment is added, usually based on inflation in the previous September, which was in the region of 10%.

In the Scottish Fiscal Commission forecasts they point out that they have based their analysis on an ‘imputed’ valuation roll due to final values not being available when they closed the forecast. Therefore, policy costings may change.

The imputed valuation roll shows that the value of the tax base has broadly risen (although it is not clear to what extent or how the tax base may have been affected by assumed appeals losses). Therefore, the poundage may have been set to fall whilst still raising a similar amount of revenue in cash terms. On top of that however, the poundage also needs to change to reflect inflation – that is the impact of inflation holding all else equal is to increase the poundage.

The final decision of Ministers has been to freeze poundage. Given the scale of inflation, it is highly likely that this would have offset any fall in the poundage arising from the revaluation alone so there will be a net cost. And indeed, this is the case – we do not have the detailed breakdown of the figures, but overall there is a net cost to Scottish Government of £308 million against the decision on poundage.

At the Budget last year, we were surprised to see Kate Forbes take an approach to reliefs that was less generous than the UK system. This year, John Swinney has seemingly taken an even more hardline approach and there are no additional reliefs applied to hospitality and retail as is the case south of the border.

There are also interesting changes afoot for the Small Business Bonus scheme, with a lower threshold and a taper system. This is arguably an improvement on the previous system which had a major cliff edge once businesses reached the eligibility threshold. The changes, still more generous than the rest of the UK, are expected to save money, although this is largely offset over the next three years due to a transitional relief scheme.

The tax block grant adjustment

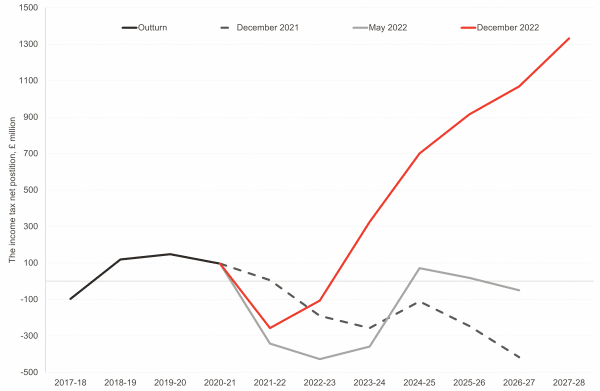

The forecasts provided by the Scottish Fiscal Commission aren’t just important as context for the support provided within the budget, but also feed into the block grant adjustment.

If the Scottish economy (or Scottish earnings) grow relatively less quickly than in rUK, then this may cause Scottish tax revenues to fall below the corresponding tax block grant adjustment (which is deducted from the budget) – a so-called negative net tax position.

SFC forecasts for the net tax position in May 2022 was -£265m, primarily driven by the negative income tax position of -£365m due to lower expected growth in the tax base in Scotland in than in rUK.

Chart 2: The Income Tax Net Position, 2017/18 to 2027/28

Source: Scottish Fiscal Commission

So, what is driving these changes?

Today’s announcements to income tax played a significant role. Increases of 1% to both the higher and top rates of income tax, combined with the reduction of the top rate threshold to £125,140, has been estimated to generate an additional £129 million for the Scottish budget in 2023/24.

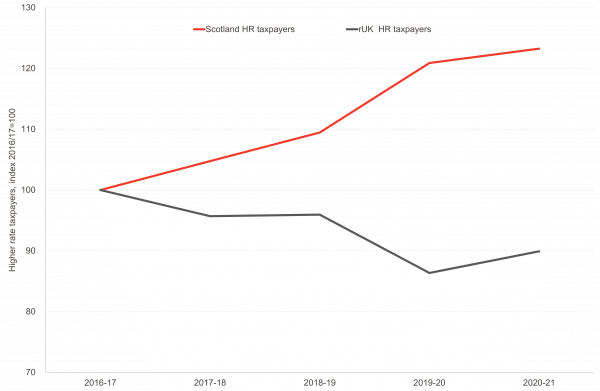

These changes to the upper rates of income tax are particularly important in the context of Scotland’s finances.

Since 2016/17 – during a period when Scotland’s income tax powers were devolved – the higher tax rate threshold in Scotland has increased at a slower pace than the rest of the UK. This has resulted in a 23% rise in the number of taxpayers paying the higher rate of tax in Scotland, whereas in the rest of the UK, there has been a 10% drop.

Chart 3: Number of Higher Rate Tax Payers, Scotland and rUK, 2016/17 to 2021/21

Source: Scottish Fiscal Commission

However, changes to Scotland’s net tax position aren’t just driven by changes in Scottish tax policy, but also by changes in Scotland’s underlying taxable income relative to the UK.

The outlook for Scottish earning growth – although still lagging behind the UK – is expected to improve in upcoming years. This is driven by several factors. Notably, geopolitical uncertainty in the energy market has stimulated economic activity across the Scottish oil and gas sector, improving the earnings and employment outlook. In addition, forecasts of UK employment growth have been revised downward, presenting a comparatively more optimistic outlook of employment in Scotland.

Spending

The Scottish Government set out its spending plans for 2023-24 in the spending review in May 2022, and we were not expecting to see any radical changes in spending allocations for 2022-23 in which many portfolios were due to see real terms cuts in their spending.

However, there are now additional consequentials of just over £1bn to be allocated for 2023-24. As discussed earlier in this article, the total amount of consequentials just offsets the effects of high inflation.

Despite additional consequentials and further revenues from announced changes to income tax, most spending portfolios are set to see a real-terms decrease in budget.

Social security

One piece of good news is a commitment to increase devolved benefit rates by 10.1% to keep up with inflation, with some of the additional revenues from changes to income tax rates and thresholds supplementing the Barnett consequential in this area.

This commitment signals an area of future budget pressure for the Scottish Government. The Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) estimate that devolved social security spending will increase from £4.2bn in 2022-23 to £5.2bn in 2023-24 (about 25%).

SFC further forecast that social security spending will reach £7.3bn in 2027-28. These increases are largely driven by a larger number of recipients and an increase in benefit rates caused by forecasted inflation, as well as a larger number of devolved benefits.

In 2022-23, the total amount needed to fund social security commitments above and beyond the amount of social security funding in the block grant was £374m; next year, it will be £776m, and in 2027-28 SFC estimates it will reach £1.4bn. These amounts must be funded by the Scottish Government out of revenues beyond the block grant.

Health and social care

Income tax rate increases will also be used to increase spending on the health and social care portfolio next year. Total spending in this area will increase by 6.2%.

Within the health and social care portfolios, the NHS Territorial and National Boards and the National Care Service and adult social care also received real-terms increases in funding.

Despite a budget increase in this general area, the status of funding for the National Care Service reform is unclear. Most of the 5.4% increase in the care service line item is likely allocated to the £100m for supporting a £10.90 real living wage for adult social care workers. The budget statement highlights that other areas of spend will “pave the way” for the National Care Service in future.

Public sector pay

The key thing we were all looking out for was the announcement on public sector pay – and we are still looking.

Departing from tradition, the Scottish Government has at this time chosen not to publish formal guidelines for public sector pay in 2023-2024.

John Swinney highlighted the uncertain outlook for inflation and a need to conclude ongoing pay negotiations as the key reasons for holding back until the new year.

Net zero

The latest budget document doesn’t delve far into any new spending on transitioning to net-zero, but John Swinney did mention several initiatives which were included in the May 2022 spending review in his speech. A new initiative, a pilot scheme trialling the removal of peak-time rail fares was the main new policy of interest announced.

Local Government

Funding for local government has been increased by £550m, representing a 3.7% increase. Whether or not this is a real terms cut depends on which forecast deflator is used – see our Budget Report for more details on this*. More analysis of what is underneath the Local Government funding line will be forthcoming in the New Year.

Equalities, low income and human rights

Alongside the Budget Statement, the government publish an Equality and Fairer Scotland Statement. This includes the government’s assessment of the impact of budget decisions on different groups of the population and the inequalities between them. The bulk of the analysis follows a similar format to previous years, with evidence presented on inequalities relevant to each portfolio area, the budget’s impact on addressing these and a note of changes in spending compared with last year.

The equalities statement has improved in recent years but could still provide further insights about the impact of decisions that the government have (and have not) made. In particular, it is still not clear the extent to which equalities considerations influence budget decisions.

There is welcome mention of human rights throughout the statement, but little evidence of robust analysis of how budget decisions will enable human rights to be realised. With proposed legislation on the table that would enshrine economic rights into Scots law, a more substantial and outcomes focused assessment of whether the budget meets the government’s human rights obligations will be needed.

In summary

Today has been an interesting day for Scottish Budget fans, with a bit of drama thrown in for good measure. We’ve had more policy changes than we expected to see, and a lot going on in the fiscal forecasts too. No doubt over the next weeks and months, more details will emerge. We hope to have an event in the spring where we delve in to this all with you in full.

*This article was updated on the 18/12/2022. The 2022/23 GDP deflator forecast was presented rather than the 2023/24 deflator forecast.

Authors

Emma Congreve is Principal Knowledge Exchange Fellow and Deputy Director at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Emma's work at the Institute is focussed on policy analysis, covering a wide range of areas of social and economic policy. Emma is an experienced economist and has previously held roles as a senior economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and as an economic adviser within the Scottish Government.

Ben is an Economist Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute working across a number of projects areas. He has a Masters in Economics from the University of Edinburgh, and a degree in Economics from the University of Strathclyde.

His main areas of focus are economic policy, social care and criminal justice in Scotland. Ben also co-edits the quarter Economic Commentary and has experience in business survey design and dissemination.

Calum Fox

Calum is an Associate Economist at the Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) and a Researcher at the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP). He specialises in economic modelling and trade, and holds an MSc in Economics from the University of Edinburgh.

Hannah is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in applied social policy analysis with a focus on social security, poverty and inequality, labour supply, and immigration.

Ciara is an Associate Economist at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She has a broad research experience across different areas including poverty and inequality, the voluntary sector, health, education, trade, and renewables and climate change. Ciara has an MSc in Applied Economics (Distinction) and a first-class BA Honour’s degree in Economics and Finance, both from the University of Strathclyde.

Allison is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in health, socioeconomic inequality and labour market dynamics.

Jack is an associate economist at the Fraser of Allander Institute.

Chirsty is a Knowledge Exchange Associate at the Fraser of Allander Institute where she primarily works on projects related to employment and inequality.