In 2017, the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act set statutory targets for child poverty rates – one set of interim targets due in 2023/24, and a final set due in 2030/31. The latest Scottish child poverty statistics for 2023/24 are due to be released on Thursday 27th March. This release is particularly important as it will tell us whether or not we have met the interim targets.

You will be hearing a lot about the interim targets over the next week, so let’s go over what they are and where they came from.

But first, a quick technical note. The advice from the Scottish Government and DWP is to use three-year averages to look at long term trends on incomes and poverty in Scotland because of the relatively small sample size. However, the child poverty targets are based on single-year data. This blog uses both the three-year average figures and the single-year figures. Next week you will see a lot of focus on the single-year figures, as these are what are used for the poverty targets.

What are the child poverty targets?

The Child Poverty (Scotland) Act was passed in 2017. It reinstated a measurable framework to tackle child poverty in Scotland following the repeal of the UK-wide Child Poverty Act. Four key income-based targets were set for the year 2030/31, along with interim targets for 2023/24. The targets are:

- Fewer than 10% of children are living in relative poverty (a measure of the gap between the poorest households and middle-income households in Scotland)

- fewer than 5% of children are living in absolute poverty (a measure of low living standards relative to 2010/11)

- fewer than 5% are living in low income and material deprivation (a measure of whether families are able to afford basic necessities)

- fewer than 5% are living in persistent poverty (a measure of the proportion of children who have lived in poverty in three or more of the last four years).

The target which you will see referred to most often is the target for relative poverty. This is the main statistic which will make headlines next week. However, the other targets are equally important for the Act.

The Child Poverty (Scotland) Act aims to tackle poverty as well as measure it, which means several policies have been brought in since 2017 to try to move the needle in the right direction. A key policy we’ll be focusing on this year is the Scottish Child Payment – more on that later.

Hopes and fears for the interim targets

The important question for next week is whether we will hit the interim targets.

In short, the evidence is somewhat mixed. The table below shows the targets and our progress as of the latest data.

Table: Child poverty targets and current progress

| Child poverty measures | Latest average figures 2020-23 | Interim target 2023/24 | Final target 2030/31 |

| Relative poverty | 24% | <18% | <10% |

| Absolute poverty | 21% | <14% | <5% |

| Low income and material deprivation | 10% | <8% | <5% |

| Persistent poverty | 14%* | <8% | <5% |

Source: Poverty and Income Inequality in Scotland 2020-23, Scottish Government (March 2024) and Persistent Poverty in Scotland 2010-2022, Scottish Government (March 2024)

*Persistent poverty figure is based on data from 2018-2022 from Understanding Society as this requires longitudinal data

The figures in the above table are concerning, with some big gaps between the latest estimates and the interim targets. However, the last set of modelled projections from the Scottish Government (published in February 2024) did show that they would meet their interim targets.

What difference will the Scottish Child Payment make?

This year’s data release will be the first year in which the Scottish Child Payment was available all year at £25 per week for all children under 16 in eligible households. We’ll be looking at changes in the overall poverty rate and whether there has been a divergence in child poverty rates for Scotland compared to the rest of the UK – this would be a clear sign that the Scottish Child Payment (which is only available in Scotland) is having a significant impact.

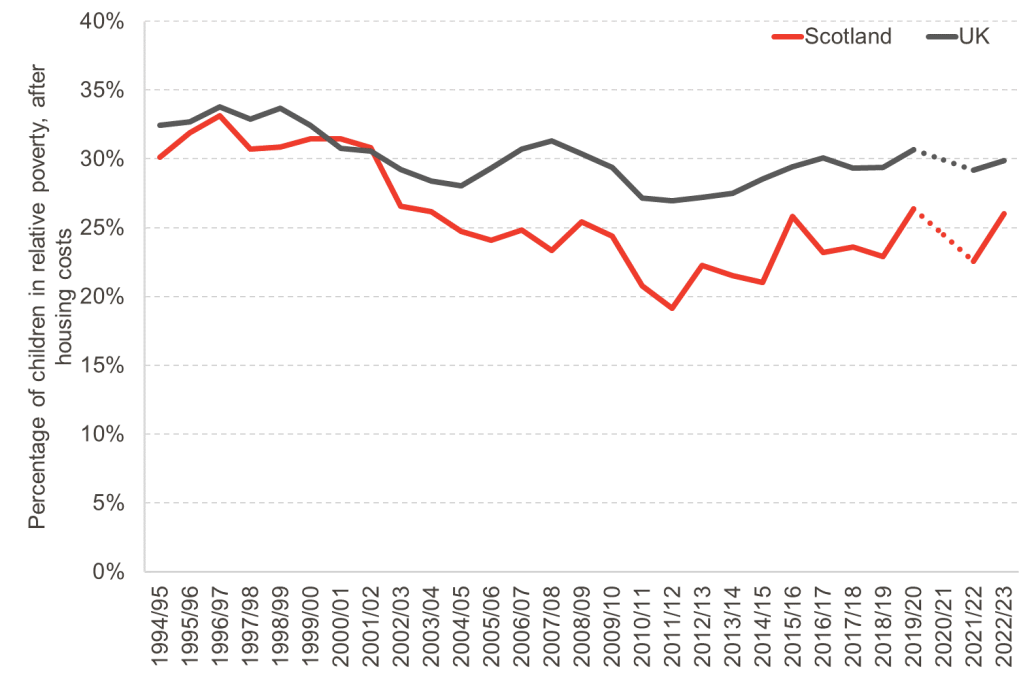

Chart: Relative child poverty rates over time – Scotland vs UK

Source: Family Resources Survey. Note: The year 2020/21 is omitted as the pandemic led to a non-representative sample

Here’s a reminder of our analysis of this chart from last year:

“The relative child poverty rate in both Scotland and the UK average rose in 2022/23. In terms of the trend over time, it looks fairly flat. Certainly we are not seeing a divergence of Scotland away from the UK average and a cynic would perhaps say it looks like the opposite may be happening.

Why is this the case? We know that take up to the Scottish Child Payment has been substantial. It will take some time to get to the bottom of it. One explanation is that the survey method is not picking up people on the Scottish Child Payment in the normal way. Or it may be that other elements of changing incomes in Scotland are offsetting the benefits of the Scottish Child Payment.” – Emma Congreve, FAI blog 2024

If poverty rates do increase or stay flat despite the addition of the Scottish Child Payment, we will likely see a lot of discussion around what factors could be pushing poverty up. In last year’s single-year data, at least part of the increase in poverty rates may have been due to the removal of support related to the pandemic (here’s last year’s blog if you want to catch up). If the trend continues, we will need to further consider which other aspects of Scottish incomes may be offsetting the impact of Scottish Child Payment.

As for the issues with the the survey method not picking up Scottish Child Payment, we’ve got updates on that too. Rather than only relying on survey data, we’ve since been made aware that DWP imputed Scottish Child Payment (SCP) figures into the Family Resources Survey for the 2022/23 year but there were instances where some households were incorrectly being allocated SCP, among other issues. In better news, the figures that will be published next week will use a new and more robust methodology (see here). We’ve had a look at this methodology and we are confident that it should perform better. We’ll have a full report out on this on Thursday 27th March.

What happens if we miss the interim targets?

If the interim targets are missed next week, the Scottish Government will need to take a serious look at why these targets have been missed. And even if we do meet the interim targets, there are still huge challenges ahead: much more ambitious action will be required to meet the final targets.

On Monday 24th March, we will be releasing a modelling report which details the cumulative impact of several potential policy levers available to the Scottish Government. The modelling includes changes to employment rates, pay, hours, changes to the Local Housing Allowance, and changes to Scottish Child Payment including global increases as well as premiums for certain priority groups. This modelling will give an idea of the scale of action required to reach the targets, and will offer insights into which policies are likely to be the best value for money as we aim for the 2030/31 targets.

Authors

Chirsty is a Knowledge Exchange Associate at the Fraser of Allander Institute where she primarily works on projects related to employment and inequality.

Emma Congreve is Principal Knowledge Exchange Fellow and Deputy Director at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Emma's work at the Institute is focussed on policy analysis, covering a wide range of areas of social and economic policy. Emma is an experienced economist and has previously held roles as a senior economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and as an economic adviser within the Scottish Government.

Hannah is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in applied social policy analysis with a focus on social security, poverty and inequality, labour supply, and immigration.