Last week, the UK Government published a white paper laying out their reforms to the immigration system. The reforms are aimed at reducing net international migration to the UK, which peaked at 906,000 in 2023 and was 728,000 in 2024.

The Government estimates that the measures announced will reduce net migration to the UK by about 100,000 people per year, although they have not set a strict target to be met.

The reforms include measures such as:

- Social care: A commitment to end overseas recruitment for social care workers, with a transition period until 2028.

- Tighter restrictions on skilled worker visas: An increase in the required qualification from RQF 3 (approximately A-levels or Highers) to RQF 6 (degree level), and an increase in the salary threshold required to obtain the visa. RQF stands for Regulated Qualifications Framework and is used in England and Northern Ireland; Scotland’s system is slightly different and uses the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF).

- Graduates: A reduction in the term of the Graduate visa, which can be obtained by people who immigrated as students and earned a UK university degree, from two years to eighteen months.

- Language requirements: Stricter requirements for the level of English required for visa applicants, including for those arriving as dependents.

- Enforcement: Tighter enforcement of compliance assessments for institutions sponsoring student visas, and an easier process for deporting those who have committed crimes.

- Settlement: An increase from five to ten years in the period of time a person must reside in the UK on a visa before obtaining indefinite leave to remain.

- Fees: An increase in the immigration skills charge, which is paid by employers sponsoring visas.

The Government has also announced plans to train and upskill UK-born workers to meet labour market demand, but have not set out full details on this.

It is also not clear yet what the impact will be on Scotland, although concerns have already arisen about the potential impact on social care and universities in particular. There is some evidence that attitudes to immigration are somewhat more positive in Scotland than in the rest of the UK, so the public response to the announced changes in Scotland may also be stronger.

Who immigrates to Scotland?

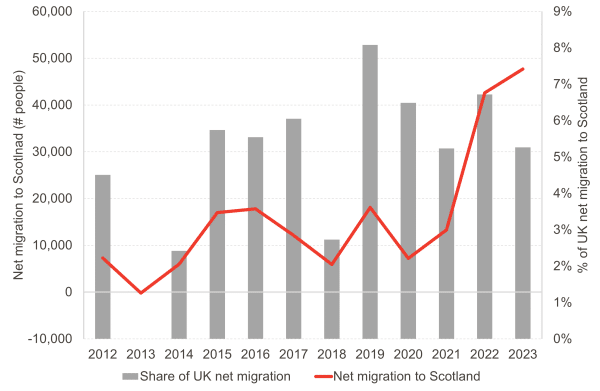

Net international migration to Scotland was about 48,000 people in the year to June 2023 (Chart 1). Scotland typically receives less than a population share of immigration to the UK.

Chart 1: Net international migration to Scotland, 2012-2023

Source: ONS and NRS

Notes: Figures are for the year ending in June of the listed year. The share of UK net migration to Scotland is not provided for the year ending June 2013, when net migration to Scotland was negative.

Net international migration to Scotland is typically centred on urban areas. Over half of net migration to Scotland in 2022-23 was concentrated in Glasgow and Edinburgh.

Over time, the composition of migrants to Scotland has changed. Proportionally more immigrants have been from outside the EU since Brexit. As of the 2022 Census, around 40% of people living in Scotland who were born in Africa, Middle East and Asia, or the Americas and the Caribbean had been in the UK less than five years, compared to about 23% of those born in Europe or Oceania.

The UK Government estimates that the measures in the white paper will reduce net migration to the UK by 100,000 people per year.

Scotland has received about 5.7% of net international migration to the UK from 2020-2023. If the reduction in Scotland’s net migration from these measures is proportional, we might expect a reduction in net international migration to Scotland of around 5,700 (about 12% of net migration to Scotland in 2022-23).

Potential impacts in Scotland

Population

Scotland has a lower proportion of non-UK-born people in its population compared to England, but immigrants play an important role demographically and in the labour market.

International migration drives population growth in Scotland and has been projected to do so until at least 2047 (the end of the projection period). Immigrants are more often younger and are more likely to have children, helping to balance an ageing UK-born population.

Labour market

Restrictions to skilled worker visas and recruitment of adult social care workers may pose challenges for Scotland’s labour market.

In the labour market, working-aged people born in Europe and Oceania have higher economic activity rates than those born in the UK. Those born elsewhere have lower rates than the UK-born population, but the gap has fallen over time.

The role of people born outside the UK in sectors such as health and social care has grown over time. Skills for Care estimates that 25% of the English adult social care workforce are not British nationals. Similar estimates are not available for Scotland. However, 12% of workers in human health and social work activities in Scotland were born outside the UK as of the 2022 Census. People born outside the UK form a larger than population share of the workforce in professional occupations, education, and information and communication.

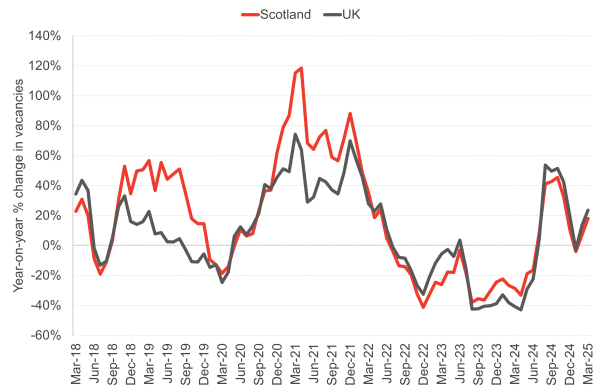

Adult social care vacancies have started to rise again in Scotland and the UK after a post-pandemic slowing of demand (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Year-on-year growth in adult social care vacancies, Scotland vs. UK

Source: ONS

The Coalition of Care and Support Providers in Scotland (CCPS) has flagged difficulties filling posts and said that they expect the immigration restrictions on recruitment of social care workers from overseas will significantly increase this challenge.

Universities

Restrictions to the Graduate visa may impact international student recruitment. These are in addition to restrictions put in place by the previous Conservative UK Government, which limited the ability to bring dependents on a student visa.

Recruitment of international students forms an important part of Scottish universities’ income. The proportion of postgraduate students coming from overseas has risen from 44% in 2019/20 to 53% in 2023/24, slightly higher than the rate for UK universities as a whole. The proportion of undergraduate students coming from overseas has stayed around 15-16% over the same period.

Part of the decision to study in the UK for those hoping to settle afterwards will be whether or not they expect to earn enough to qualify for a Skilled Worker visa after their Graduate visa runs out. We conducted analysis of typical pay rates for Scottish graduates compared to the Skilled Worker salary thresholds in our report last year.

Fiscal impact

The Scottish Government faces a tight fiscal environment. These reforms may pose additional challenges to the Scottish economy without offering much in the way of solutions.

The immigration reforms will not directly result in additional Barnett consequentials. Additional immigration fee revenue funds Home Office operations and does not feed through to the Scottish Government.

However, education is devolved. If the UK Government increases spending on training programmes for UK-born workers in England and Wales, the Scottish Government will receive additional funds through the block grant settlement.

Since migrants are on average younger, they help to increase the working-age tax base. Evidence suggests that, on balance, immigrants to the UK pay more into the tax and benefit system than they get out. This is particularly true for newer arrivals without indefinite leave to remain, who often do not have recourse to public funds (i.e., they cannot apply for benefits) and pay significant visa and health fees on arrival, leading in some cases to financial hardship.

The Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) has modelled immigration as a net positive for UK growth over the next five years. The UK Government has argued that they are considering long-term impacts as those who settle in the UK age and draw more on public funds, and there is a possibility that they will ask the OBR to reconsider how they model the contribution of immigration.

The changes will still be debated and may change before being implemented. We’ll be looking out for further developments on both the training plans and how immigration is modelled in the OBR’s forecasts, as well as further evidence on how the immigration rules may impact Scotland.

Authors

Hannah is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in applied social policy analysis with a focus on social security, poverty and inequality, labour supply, and immigration.