After a busy week of economic and fiscal data, we’re back with more on Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland, to address some of the questions we’ve been asked by folks in the media and also emails we’ve received from you guys.

The UK public sector debt interest bill increased a lot in 2022-23, but is expected to settle at a lower level than in that year

A big talking point was the increase in debt interest payments on the UK’s public sector net debt apportioned to Scotland, after it doubled from £4.6 billion in 2021-22 to £9.2 billion in 2022-23. It’s worth noting that apportionment of debt interest in GERS is done on a population share basis, and so this simply reflects the UK Government’s more than doubling of the whole debt interest bill, which was driven by both higher inflation and higher interest rates.

Higher inflation leads to higher debt interest payments because the UK Government has issued inflation-proof gilts, also known as “linkers”. These gilts ensure that investors holding them have a guaranteed real rate of return in each year, and so the UK Government pays higher interest rates the higher inflation is in any given year (and vice-versa).

So why does the UK Government do this?

It’s because if investors are guaranteed a certain real return, the gilt being sold is more attractive, and so they are willing to pay more for it – which lower the interest rate paid by the UK Government. So in normal times, with low and predictable inflation, linkers tend to save the UK Government money – but in 2022-23, the opposite was true.

The OBR expects inflation to fall sharply in the coming years, and we are already seeing it a much lower level than just a few months ago, so this will have been a one-off effect, even if it was an expensive one.

However, the underlying interest rate being charged on UK gilts has gone up significantly, and as more debt is issued and refinanced, these higher rates spread to the UK’s stock of debt. (The OBR has also done some analysis on how and why the maturity of the UK’s debt is shorter than it ever has been, but it’s one for the fiscal aficionados). This effect though is expected to remain in the coming years.

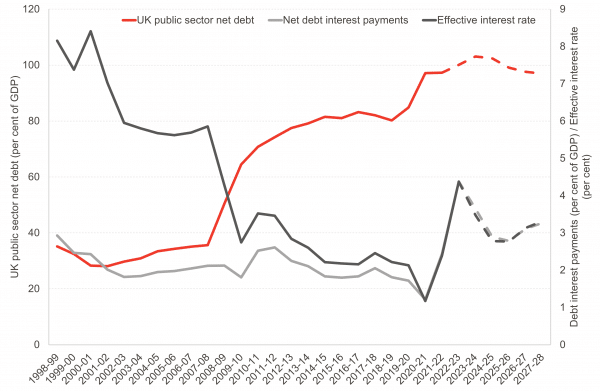

Chart: UK public sector net debt, debt interest payments and effective interest rate

Source: OBR (FAI calculations). Dashed lines represent OBR forecasts

Since the late 1990s, UK debt as a share of GDP has increased significantly, from under 40% to around 100%, with large spikes after the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic. But despite the large increase in the stock of debt, interest payments actually fell as a share of national income, first as inflation fell and then as investors looked for safer assets during big shocks.

But with the increases in inflation and rates in 22-23, the effective interest rate (debt interest payments divided by the total debt stock) nearly doubled.

Debt interest is now expected by the OBR to settle at a significantly higher level than it was pre-pandemic, although not dissimilar to where it was the late 1990s – because despite the higher debt stock now, interest rates remain much lower. If the OBR is right, that would mean GERS showing between £6 billion and £8 billion of apportioned debt interest payments in the coming years, rather than the £9.2 billion in 2022-23.

How does Scotland’s revenue and expenditure compare with other countries?

We were also asked how Scotland’s position compares with that of other countries. GERS not only contains data for financial years and on a public sector-wide basis – the way revenue and expenditure is used for UK public finances – but also for general government (that is, excluding public corporations) and on a calendar year basis, which can be used for international comparisons.

There are a few steps needed to ensure comparability (for both UK and Scotland figures), but once we account for that, the picture below emerges for 2022:

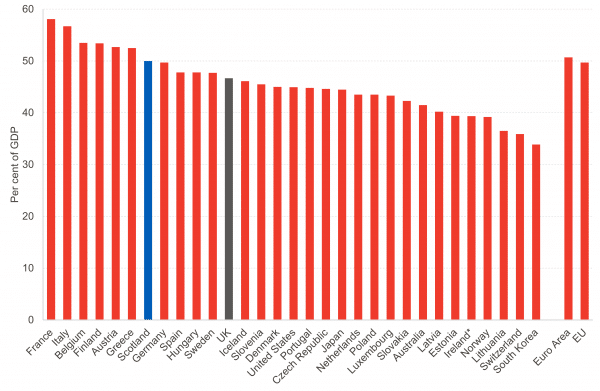

Chart: Scotland and UK government expenditure in 2022 in international context

Source: Scottish Government, OECD, Eurostat, Central Statistics Office Ireland (FAI calculations)

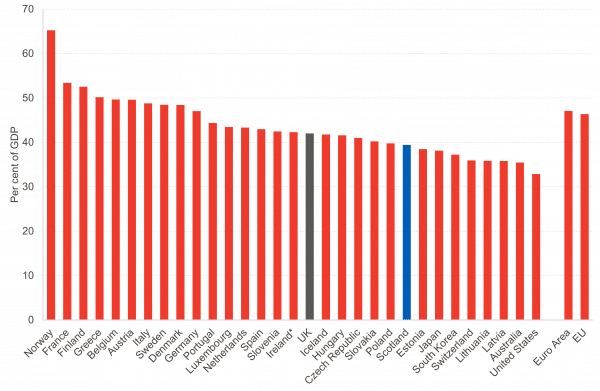

Chart: Scotland and UK government revenue in 2022 in international context

Source: Scottish Government, OECD, Eurostat, Central Statistics Office Ireland (FAI calculations)

*Note 1: Ireland’s revenue expenditure as a share of national income is calculated using modified GNI rather than GDP, in line with the recommendations from the Central Statistics Office

* Note 2: Revenue and expenditure for Switzerland, Japan, South Korea, Australia and the United States is for 2021 (2020 for South Korea) due to comparable data not yet being available.

Scotland’s expenditure on a comparable basis for 2022 was 50% of GDP, 3.3 percentage points higher than that of the UK as a whole. This is towards the top end of the countries in the chart, but very similar to the Euro Area and EU averages, and around the same level as some of the comparator countries highlighted by the Scottish Government such as Austria, Belgium, Sweden and Finland.

But while those countries also have government revenues around 50% of GDP, the same cannot be said for Scotland, where revenues in 2022 were around 39% of GDP, and much lower than the EU and Euro Area averages. This is a significant difference, and puts Scotland’s revenue much closer to that of economies such as Switzerland, Poland and Estonia, all of which have much lower public spending.

What does GERS tell us about independence?

When we published our blog on Wednesday, we said:

GERS takes the current constitutional settlement as given. If the very purpose of independence is to take different choices about the type of economy and society that we live in, then it is possible that these a set of accounts based upon the world today could look different, over the long term, in an independent Scotland.

That said, GERS does provide an accurate picture of where Scotland is in 2023. In doing so it sets the starting point for a discussion about the immediate choices, opportunities and challenges that need to be addressed by those advocating new fiscal arrangements. And here the challenge is stark, with a likely deficit far in excess of the UK as a whole, other comparable countries or that which is deemed to be sustainable in the long-term. It is not enough to say ‘everything will be fine’ or ‘look at this country, they can run a sensible fiscal balance so why can’t Scotland?’. Concrete proposals and ideas are needed.

We’ve been asked a few questions about this, such as what examples there are of politicians or others saying “everything will be fine” and also what sorts of “concrete proposals” we might be talking about.

On the first point, the most recent example is the third paper in the Building a New Scotland series, “A stronger economy with independence”. As we said when it was published:

One of the difficult questions that this paper does not address head on is the likely starting fiscal position of an independent Scotland, and how the Scottish Government plan to meet the fiscal rules they discuss.

It is said in the paper that it is not possible to know what this would be given wider uncertainty. However, we do know the levels of revenue and expenditure under the current constitutional arrangements.

These figures are referenced in the paper. But the substantive issue – of how we would transition from current levels of revenue and spending to something more sustainable, in line with the desired fiscal rules – is not addressed. The uncertainties in the world economy right now simply make that challenge harder – but are not an excuse for not addressing this challenge.

In terms of the concrete proposals that could be considered, it could be something along the lines of the plans that were set out by the Sustainable Growth Commission in 2018, which set out a pathway for reductions in public spending and assumptions about improvements in economic growth to help ensure that the public finances were on a sustainable path. Of course, it is easy to assume there will be higher levels of economic growth in order to improve the fiscal position, but it would also be important that folks advocating for independence set out how this higher growth will be achieved.

Thanks to everyone who took the time to get in touch with your questions – have a great weekend. It’s a bit of rest and recuperation for us after a very busy week of analysis!

Authors

Mairi is the Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, she was the Deputy Chief Executive of the Scottish Fiscal Commission and the Head of National Accounts at the Scottish Government and has over a decade of experience working in different areas of statistics and analysis.

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.