Firstly, apologies for the long weekly update… a lot has come out this week! We’re still digesting a lot of these documents, so we might say more in the weeks to come.

The long-awaited plan from the Scottish Government on the plan for Public Service Reform was published yesterday. It is (by the standards of these things) a pretty short, clear and punchy document – only around 40 pages for the main body of the document and is very readable and accessible.

Public service reform is vital, as for many years it has been clear that public services as currently delivered are likely to be unsustainable in the medium to long-term.

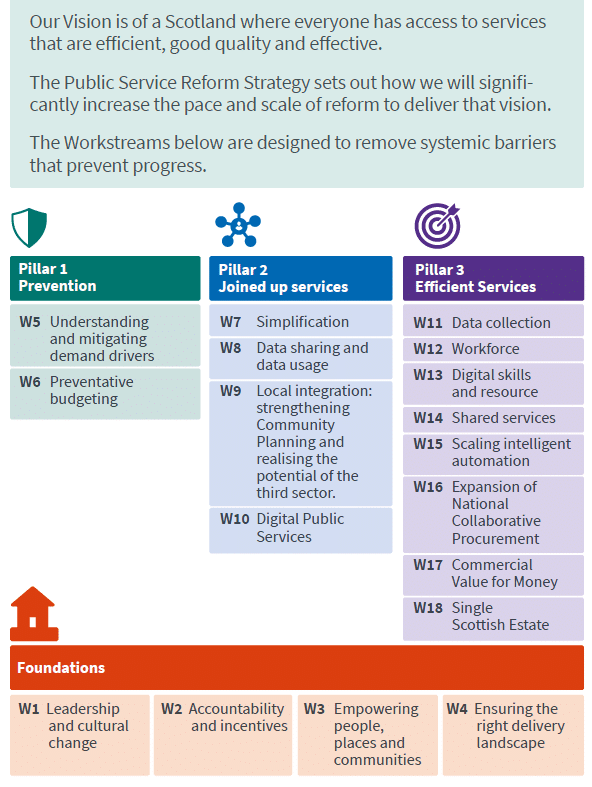

There are four main areas of action set out to reform public services in Scotland, set out neatly in the diagram below:

Figure: The Scottish Government’s Approach to Public Service Reform

Source: Scotland’s Public Service Reform Strategy — Delivering for Scotland

There are many interesting specifics to dig through under each of these headings. The “Foundations” actions include a large focus on cultural change within the public sector, and also a review of the National Performance Framework to ensure proper accountability.

Many of us who have analysed the delivery and design of public services in Scotland over the last 15-20 years would reject the notion that the National Performance Framework is currently a key driver of prioritisation and focus on outcomes-based policy – there is simply no evidence that this has been the case. If it is to become relevant for driving change, then it will not only have to be reviewed and refreshed but also properly embedded in the accountability framework within the Scottish public sector.

The actions under “Ensuring the right Delivery landscape” may include consolidation of public body functions, as part of many other actions for streamlining the public sector, including a presumption against new public bodies being created. Without explicitly saying it, this feels like the SG indicating that there are too many public bodies in Scotland, and opportunities will be looked at for consolidation.

The prevention pillar, whilst covering the smallest number of actions, is likely to be the meatiest in terms of significantly changing what and how we are delivering in public services in Scotland. The overall idea is a shift to spending a little today to avoid much more spending tomorrow (or rather, in 5,10, 20 years’ time).

The narrative on focussing on prevention is not new. The document says:

“We know there is commitment right across the public services system to a preventative approach, and many examples of success, but we have not made sufficient change to ensure our system is prioritising prevention.”

Attempts have been made in the document to calculate the benefits of prevention, in the form of “avoided cost”. The policy areas shown are poverty, obesity and smoking. It is welcome to see the effort to put numbers on these benefits, as it helps evidence the benefits that up front spending in an area can have in terms of avoided, more costly spending later. This can help make the case for taking a preventative approach.

However, measuring these avoided costs is a difficult area (which is fully acknowledged in the document), and more research is definitely required to build a better evidence base, not only to make the case for preventative approaches, but also to choose between them when we have several options on prevention. For example, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) numbers from 2016, which are used to calculate the poverty “avoided spend”, were not produced for this purpose and are probably not well suited to this use. This is not to criticise the Government’s attempt to do this, but to say that we need more evidence to produce numbers on a better basis.

This pillar’s success will be measured by the following metrics: “We will measure preventative spend by Government and track that the proportion of spend on prevention increases and the resultant spend on acute/crisis decreases.” We would hope that more detail on this will be published as part of the Theory of Change and Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Framework that the Government say they will publish. In particular, it will be good to see how the linked resultant acute spend will be identified.

The second pillar, joined up public services, will be measured by:

- Measure the impact of services against required outcomes.

- Measure cost reductions and cost avoidance generated by service change, and the proportion of those savings invested in further change.

Whereas the third pillar has quite a specific metric attached:

- Over the next 5 years we will reduce annualised Scottish Government and public body corporate costs by £1 billion, representing around 20% of the identified public body corporate and core government operating costs.

It is not clear how the different actions in the Efficiency section are likely to contribute to this aim to reduce corporate costs, so it is hard to judge how realistic this is. AI, digital adoption, shared services and so on are cited as ways to improve efficiency, but a cut of this size is ultimately going to have an impact on the workforce and perhaps will have consequences for public sector pay.

There is a section on workforce, but there are no specifics on workforce size, productivity or pay levels in the document. Given pay makes up over half the Scottish Government’s Budget, this seems a key omission from this document. The PSR document says that the SG will “take steps to reprofile our public sector workforce” and that this will be presented as part of the Fiscal Sustainability Delivery Plan which will be published next week alongside the Medium-Term Financial Strategy, on 25th June.

We await this information with interest – which is likely to help us work out what the PSR Efficiency section could mean in practice.

Population Health Framework released

The Scottish Government and COSLA have co-produced a new Population Health Framework, which sets out their long-term collective approach to improving Scotland’s health and reducing health inequalities for the next decade. Public Health Scotland, working alongside Directors of Public Health in Scotland, played a key role in developing the framework, including by contributing to a linked evidence review.

The Framework champions primary prevention and whole-system collaboration to narrow Scotland’s socioeconomic health gap. Its evidence review is persuasive, yet most concrete actions stay within health and social care, while specific cross-government actions to tackle key social determinants of health, such as housing, are more limited.

Given this, having this released in the same week as the plan for Public Service Reform poses interesting questions and perhaps challenges for the government. The PSR strategy talks a good game about less silo working to ensure that public services are sustainable, but in the same week there is an example of where an opportunity to demonstrate this has perhaps been missed.

See the initial response from the Scottish Health Equity Research Unit, which is a partnership between the FAI and the Centre for Health Policy at Strathclyde, funded by the Health Foundation.

Minimum Income Guarantee report released

In their 2021 manifesto, the SNP committed to exploring the possibilities for a Minimum Income Guarantee (MIG) in Scotland. This week, the MIG Expert Group published their final report, which maps out a path to delivering a MIG.

A MIG would apply to everyone and provide a minimum standard of living through employment, target welfare, and other support as part of a strategy to reduce poverty and deprivation. The report proposes the use of the Minimum Income Standard, which is published annually, to calculate the level of the MIG. Other key parts of the proposal include Universal Basic Services, which would provide essentials for free or at affordable prices; a separate payment for housing costs that would reflect geographic variation; and a structure that encourages paid work, take-up, and ensures accessibility.

The MIG Expert Group’s report sets out a potential roadmap for delivery. The first five-year stage would focus on what can be done within devolved powers. We provided some modelling of some of these recommendations, which you can read about here. Future stages would then introduce an interim MIG set at the relative poverty line, which would be time-limited for those who are able to work.

The hope is that a MIG would essentially eliminate poverty and provide an assured minimum standard of living, enabling people to choose to change jobs, go back into education or training, raise children, or make other choices without risking poverty. The con, of course, is that it would be very expensive; the interim MIG is estimated to cost £5.9 billion if implemented today (about what is currently spent on devolved benefits), but would cost less if incomes improve before implementation.

Given the cost and current budgetary pressures, it’s hard to imagine that a MIG will happen in the near future. However, having the proposal (and all the background work that went into it) in the public domain may shape the conversation about how to raise living standards and reduce poverty in Scotland.

Prevention discussion round up

Interestingly, the MIG report also feeds into the discussion on prevention: asked on GMS if, for example, spending on a MIG could divert spending from the NHS, the social security Cabinet Secretary Shirley-Ann Somerville said “no”. But, if it reduces poverty and therefore health issues, couldn’t that ever be a possibility?

The discussion on prevention is going to be difficult if we don’t recognise that we should be targeting interventions to reduce demand on the NHS because the current trajectory for both demand and funding is unsustainable. This might mean, over time, we are looking to spend more on services which might be outside the NHS, or even health, in order to reduce the need for acute NHS services. Perhaps even, in time, this would mean we spend relatively less on the NHS, although that may not be possible given our demographic outlook.

To be clear, we are not advocating for this policy specifically, it is just an example of the kind of honest discussion that we need to have in the prevention space. If the input spending on the NHS is an untouchable sacred cow, no matter the outcomes it achieves, then we are going to struggle to really make the shift that we need to in order to make public services sustainable.

Our latest podcast with Deloitte

The FAI and Deloitte are partnering on the podcast series “Driving Growth: Innovation and Sustainability in Scotland”, which is exploring the role that the energy transition and digital adoption and diffusion can have in driving growth in Scotland.

Our latest podcast focusses on financing the energy transition, with Netti Farkas-Mills, Senior Insight Manager for Energy, Resources, and Industrials at Deloitte, and Jamie Spiers, Deputy Director for the Centre for Energy Policy at Strathclyde. This focusses on some fascinating recent research published by Deloitte, featuring an extensive survey of current and potential investors.

Authors

Mairi is the Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, she was the Deputy Chief Executive of the Scottish Fiscal Commission and the Head of National Accounts at the Scottish Government and has over a decade of experience working in different areas of statistics and analysis.

Hannah is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in applied social policy analysis with a focus on social security, poverty and inequality, labour supply, and immigration.

Allison is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in health, socioeconomic inequality and labour market dynamics.