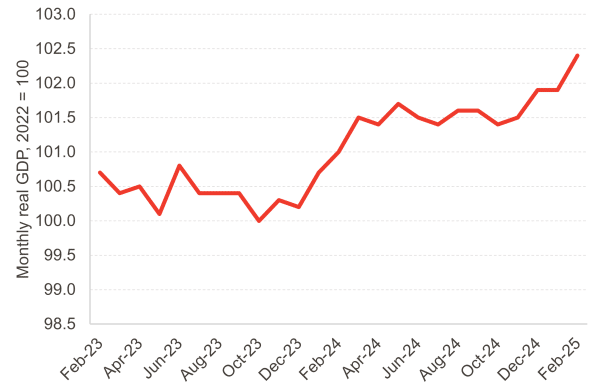

This morning the ONS released its estimate for UK GDP in February. It was a much more upbeat reading than we have become accustomed to in recent times, with output growing by 0.5% on January.

It’s foolish to read too much into a single month’s GDP figure. Monthly data is quite volatile, and we have seen months of spurting growth being followed by much slower ones, even in the last few years. Nonetheless, it’s good news for the UK economy.

Chart 1: Monthly UK real GDP in the last three years

Source: ONS

The source of growth is also quite interesting. The largest positive contributions have come from three sectors – manufacturing, wholesale and retail (including the motor trade) and information and communication services. These are all sectors that are relatively important for the UK economy, but whose performance has been disappointing in the post-Covid era. Manufacturing output, for example, is still below its June 2023 peak even after the latest reading.

This release is also interesting because of the sectors that didn’t contribute significantly to growth in February, in contrast with other recent months. Health and social care activity was broadly flat on January, and professional services output fell by 0.5%. These are large sectors, each accounting for roughly 8% of the UK economy, and therefore these readings have tempered somewhat the overall figures.

One swallow doesn’t make a summer

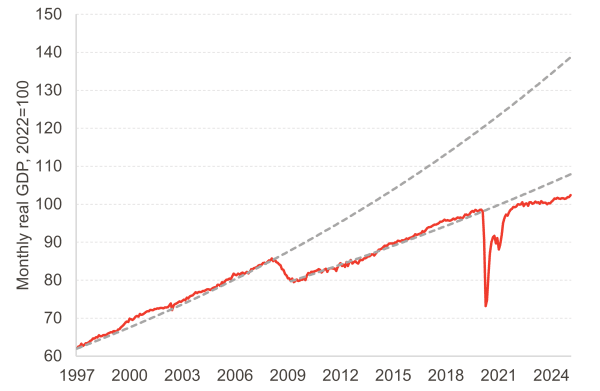

All the optimism aside, it’s worth putting the latest figures for GDP in a bit of historical context. 0.5% growth in a month is great, but we shouldn’t expect every month to be like this, and even with a stronger start to 2025 than anticipated, we are still well below trend growth in previous decades.

Chart 2: Monthly UK real GDP since 1997

Source: ONS, FAI analysis

The annualised growth rate since the pandemic has been around 1% for the UK, well below the 1.9% from 2009 to 2019 – which was itself a far cry from the 2.9% average between 1997 and 2008. It would take several quarters of strong growth to shift the dial towards a more positive mood, and we should all know better than to overinterpret a single data point.

The tariff gameshow rolls on, and so does uncertainty

The United States has continued to alter its trade policy on the fly, this time seemingly in response to a set of disastrous days in the financial markets, in which investors started shunning all dollar denominated assets.

The US President rowed back on his so-called ‘reciprocal’ tariffs, bringing them down to a 10% blanket tariff for a 90-day period for all countries except China. The rate for goods imported from China is now (we think?) 145%, but the levels are so extraordinary that we are heading to what is nearly a de facto embargo on direct trade between the two countries – especially after China also retaliated with tariff rates of 125%.

Goods from the UK were already going to face a 10% tariff, so this changes little for UK producers. What it does mean is that trade will be less disrupted across the world than would have been the case, especially as other countries too have paused their retaliation against the US.

This, of course, is still bad news compared to a few months ago. It’s akin to someone dropping two ten-pound notes down the drain, and after much wrangling managing to snatch back one of them. Of course, you’d rather have one tenner than none, but you’re still worse off than before.

One thing that hasn’t changed significantly is the level of uncertainty and volatility. For example, the Cboe Volatility Index – a measure of volatility in the financial markets – remains near post-pandemic highs. It’s pretty clearly folly to try and predict what might come next, and that is why we wouldn’t be surprised to see a slowdown in investment and durable goods purchases, both in the US and across the world.

That would slow down economic growth, which would spell bad news for the UK economy. We might have seen better figures than expected for the beginning of the year, but growth needs to be sustained to deliver improvements in living standards – which feels hard in the face of the uncertainty permeating the international trading system.

Authors

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.