Peter Thorpe, a 4th year economics student at The University of Strathclyde, carried out independent research on the Scottish Humankind Index over last summer. This blog summarises his research.

The Humankind Index was developed in 2011 as a means of measuring wellbeing in Scotland beyond using standard economic measures like GDP. The Index consisted of 18 sub-domains encompassing a wide variety of factors such as health, access to good facilities, employment and job satisfaction etc.

This research constructs an updated index using modern data. Changes in data availability since 2011 have necessitated the selection of many new measures for the sub-domains.

Click here to read Peter’s full article on his research

Introduction

The Humankind index was originally developed in 2011 by the Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) in collaboration with Oxfam Scotland as a means to quantify wellbeing in Scotland, beyond simply using traditional economic measures, and to track changes in wellbeing over time.

The index comprised a comprehensive set of sub-domains that encompassed several factors that influence the quality of life and prosperity of the Scottish populace. Many of the measures of wellbeing were taken from survey data, and thus it was based largely on subjective opinion and self-assessed wellbeing.

However, since 2011 the data collected by the Scottish Government has changed. In particular the Scottish Household Survey (SHS) underwent significant revisions in 2012 that mean that many of the measures from the original index are no longer available and substitutes must be found.

This research aims to create a new Scottish Humankind index for 2017 using measures that best fit from new SHS data. There was also a separate Humankind index created for deprived communities and gender split indices for males and females, in order to identify both geographic and gender inequalities in Scottish wellbeing.

Humankind Index sub-domains

One of the first steps in the creation of the Humankind Index was a consultation with people from all over Scotland carried out by FAI and New Economics Foundation (NEF) that sought to identify what factors people consider most important to living a good life.

The 18 index sub-domains are –

- Affordable, decent home and safe home to live in

- Physical and mental health

- Living in a neighbourhood where you can enjoy going outside and having a clean and healthy environment

- Having satisfying work to do (paid or unpaid)

- Having good relationships with family and friends

- Feeling that you and those you care about are safe

- Access to green and wild spaces; community spaces and play areas

- Secure and suitable work

- Having enough money to pay the bills and buy what you need

- Having a secure source of money

- Access to arts, hobbies and leisure activities

- Having the facilities you need locally

- Getting enough skills and education to live a good life

- Being part of a community

- Having good transport to get to where you need to go

- Being able to access high quality services

- Human rights, freedom from discrimination; acceptance and respect

- Feeling good

The consultation also determined the weighting given to each factor, reflecting their relative importance. Factors with higher weightings contribute a greater amount to the total index score.

A suitable measure used to measure Scottish performance in each factor was selected and calculated to construct the Humankind Index as a weighted sum. To date these weightings have remain unchanged, yet many of the measures now used are different, either because the old measure is no longer available or a new and better one is available.

A review and update of data for each Index sub-domain

We now take each of the sub-domains of the Humankind index in turn, and select the best-fitting measure available. In some cases, this is the same as in the original index but for most sub-domains changes in available data necessitate the use of a new measure.

For example, in sub-domain 3 – ‘living in a neighbourhood where you can enjoy going outside and having a clean and healthy environment’ – the original measure is no longer available and a new measure must be found.

The measure in the original index was from a question in the SHS that asks if respondents agree or disagree with various statements about their neighbourhood. One of those statements was that they lived in a “pleasant neighbourhood” and the percentage who agreed was used as the measure.

This question is no longer in the SHS. The new measure is the percentage who rate their neighbourhood as a “very good place to live”. In 2017 this figure was 57%. This measure is as close as possible to the old one, and it can be reasonably assumed that a “very good” neighbourhood would be clean, healthy and suitable for outdoor activities.

The 2017 Humankind Index

To calculate the new 2017 Humankind Index the score for each sub-domain was found by multiplying the calculated measures – new and updated as discussed above – by the weighting ascribed to each sub-domain via the original 2011 consultation. The scores were added together to produce the total value of the index for 2017.

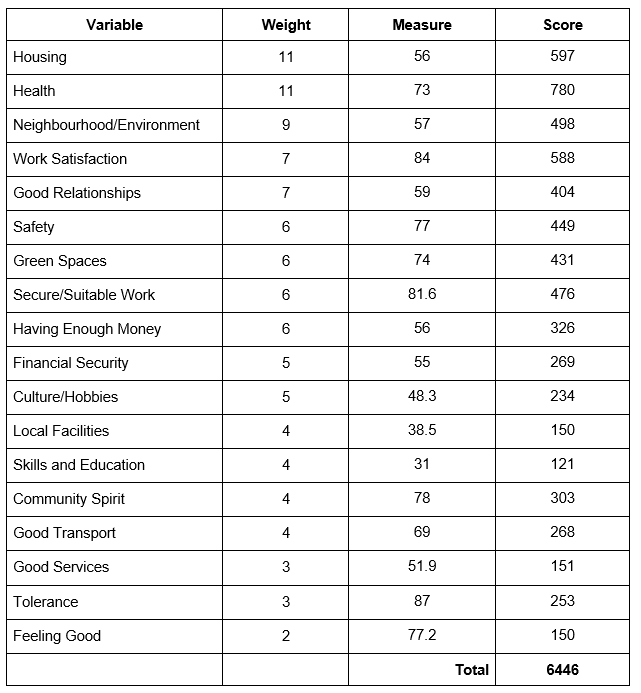

Table 1: The Humankind Index, sub-domain weights, values and scores, 2017

As an absolute value the size of the index has little meaning. Its value lies in comparisons over time and the relative sizes of the portions of the index.

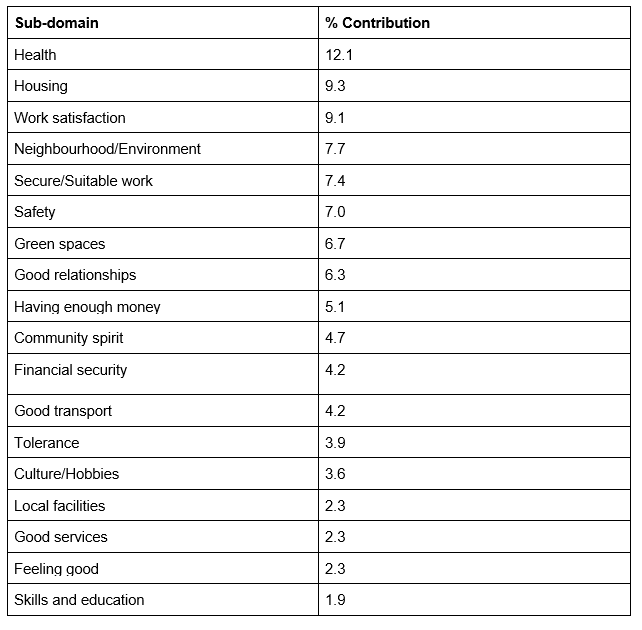

Table 2 below shows the percentage contribution of each sub-domain to the index, calculated by dividing the sub-domain score by the total score for the index and multiplying by 100.

Thus the % incorporates both the weighting and the measure, and gives a rough idea of which sub-domains are contributing the most to wellbeing in Scotland.

Table 2: The percentage contribution of each sub-domain to the Humankind Index (2017)

Changes in the Humankind Index over time

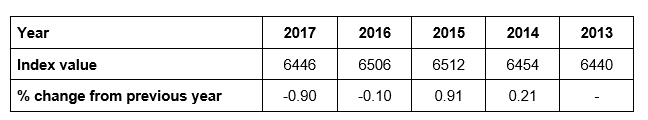

The availability of data and use of recently adopted measures means that 2013 is as far back as the index can track. Table 3.

Table 3: Value of the Humankind Index and percentage change from previous year, 2013 – 2017

The index value has remained fairly stable over the period. A small rise from 2013 to a peak in 2015 was followed by an almost equal drop in the following two years, and the 2017 index is only 6 points higher than it was in 2013.

Thus, it appears wellbeing in Scotland has not grown in any significant sense in the past four years. However, while the total index value has remained roughly steady, some of the individual sub-domains have displayed notable trends. Some have improved, some have worsened and others have fluctuated without any discernible pattern.

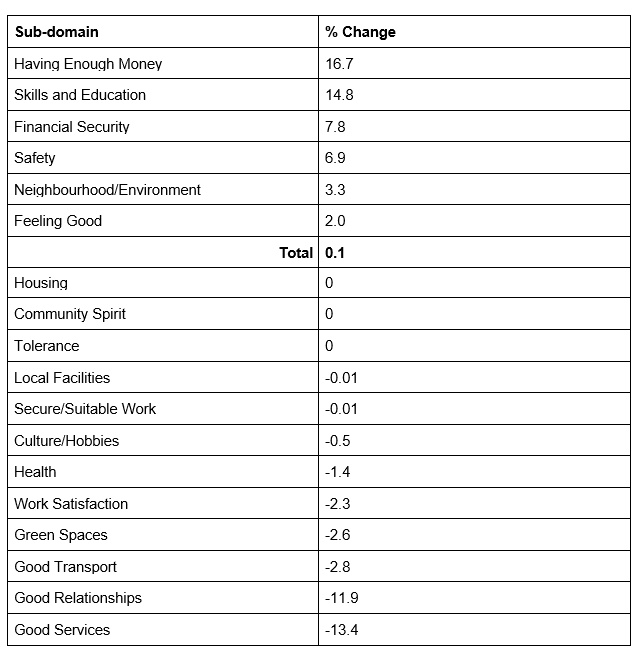

Table 4 ranks the percentage change in sub-domain scores from 2013 to 2017, by largest increase to largest decrease.

Table 4: Percentage change in Index sub-domain scores, 2013 – 2017

When one looks at performance over time at the sub-domain level, it is evident that it has improved for six, remained unchanged for three, and – interestingly – worsened for nine (although the decrease in two – access to local facilities and suitable work – is so small as to be negligible).

The Humankind Index and deprived communities

A key aim of the index is to examine how Scotland’s most deprived areas are performing relative to Scotland as a whole. The most deprived areas are found through the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). A separate index has been constructed using data collected solely from households from the most deprived data zones of the SIMD.

Due to limitations of data, not all the Humankind Index sub-domain measures could be decomposed to the level of SIMD data zones so the following five sub-domains are, for now, excluded from when using SMID data sets: Secure/suitable work, financial security, culture/hobbies, local facilities, and feeling good. Due to a lack of data for 2017, the most recent SIMD data are for 2016.

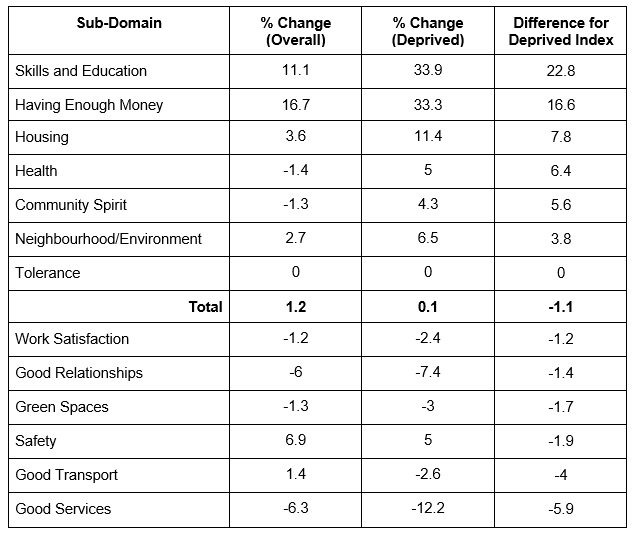

A useful analysis is to compare the percentage differences between the scores from the 2013 deprived index and the 2016 index to see how the sub-domains have changed over time. By comparing these differences to the differences for the overall index, it can be seen whether deprived areas are catching up or falling behind Scotland as a whole. Table 5 lists the sub-domains in order of largest relative gain for deprived communities to largest relative loss.

Table 5: Percentage changes in sub-domain scores between overall Humankind Index and Deprived Index

From Table 5 it can be seen that deprived communities gained by only 0.1% between 2013 and 2016, compared to a gain of 1.2% for Scotland over the same period. This suggests wellbeing is lagging behind in deprived communities; however, some individual sub-domains did see a relative improvement. Much like the overall index, education and economic sub-domains saw the largest increases. While performance in these sub-domains still lags far behind the rest of Scotland, it does appear that deprived areas are catching up.

Relative gains in health, housing and neighbourhoods are also welcome signs of a convergence in living standards. Conversely, however, public service satisfaction is dropping faster in deprived communities – communities that rely more than the average on public services for their wellbeing and security.

Gender differences

In order to examine changing gender equality in Scotland, separate indexes for males and females were constructed. As with the deprivation index, data limitations mean the most recent index that is available is for 2016, and some sub-domains had to be excluded: financial security, culture/hobbies, local facilities, good transport, good services, and feeling good.

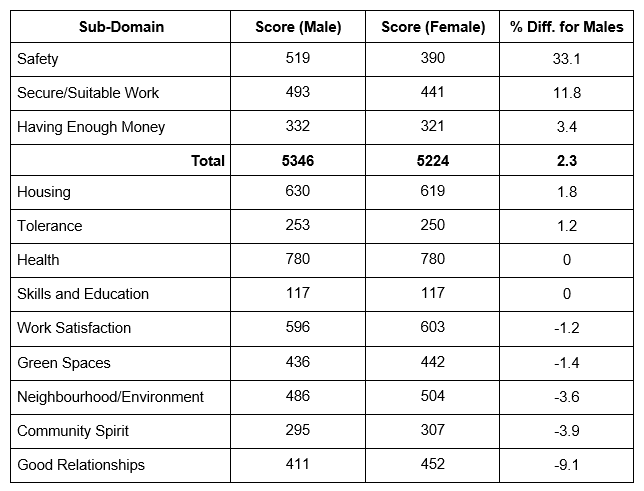

By comparing the two indexes it can be seen that is slightly higher overall for males, although some sub-domains are higher for females. Table 6 ranks those sub-domains with highest percentage gain for males to the highest percentage gain for females.

Table 6 Gender differences in wellbeing – Male vs Female 2016 Index

There are five sub-domains that are higher for males, five higher for females and two where there are no differences. However, the sizes of the differences are not equal.

From Table 6 it is clear that the higher total wellbeing for males is largely a result of greater feeling of safety and higher wages. Conversely for females it appears they have better relationships and a higher sense of community spirit. With regards to differences in satisfaction with housing, neighbourhoods, and green spaces, from this data alone it cannot be determined if men and women display different patterns in living standards or if men and women tend to have different standards for, for example, what constitutes a “good neighbourhood”.

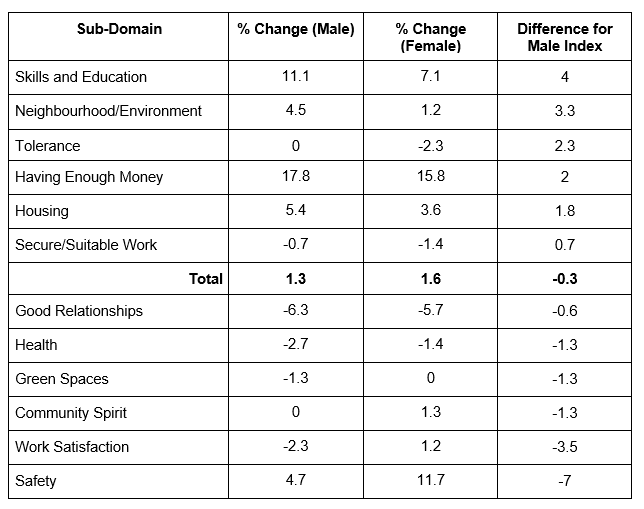

Finally, a comparison of changes to both indices over time can reveal if the wellbeing gender inequality gap is closing or widening. Table 7 lists the sub-domains ranked from those with greatest relative increase over time for males to greatest relative increase over time for females.

Table 7: Changes to sub-domain scores, 2013-2016: Male Index vs Female Index

These results suggest the wellbeing gap has closed slightly as the female index rose by 0.3% higher than the male index over the period. The largest relative increase for females was in safety. Although safety was by far the worst performing measure for females compared to males, it does appear to improving.

There is however evidence of divergence among several sub-domains. Other than safety, neighbourhood/environment was the only other sub-domain that appears to show that the gap is closing, while all of the rest display divergence. For example, work satisfaction had a greater relative rise for females from 2013 to 2016, and was higher for females in 2016, suggesting that the work satisfaction gap between males and female has increased rather than decreased in favour of females.

Thus while the overall gap has decreased slightly, this was driven mostly by improved safety for women while in the majority of sub-domains the equality gap widened.

Conclusions

Tracking this new index over time shows total wellbeing has remained largely unchanged since 2013. There were large improvements in financial measures but decreases in satisfaction with public services and personal relationships.

Separately, more limited indices were created for male and females, as well as the most deprived areas of Scotland. These show a small but persistent gender gap in favour of males and that deprived areas continue to lag behind the rest of Scotland in terms of wellnesss.

Overall, there is still a need for more and improved data sources (and linking) to make the index more accurate and comprehensive.

Click here to read Peter’s full article on his research

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.