Stuart Balfour is a third year undergraduate economics student at the University of Strathclyde and is participating in a summer internship in the Fraser of Allander Institute supported by the Carnegie Trust. This blog summarises some of Stuart’s research into trends in Scottish housing over the last two decades, using data from the Family Resource Survey (FRS) – a detailed annual survey of UK households published by the Department of Work and Pensions.

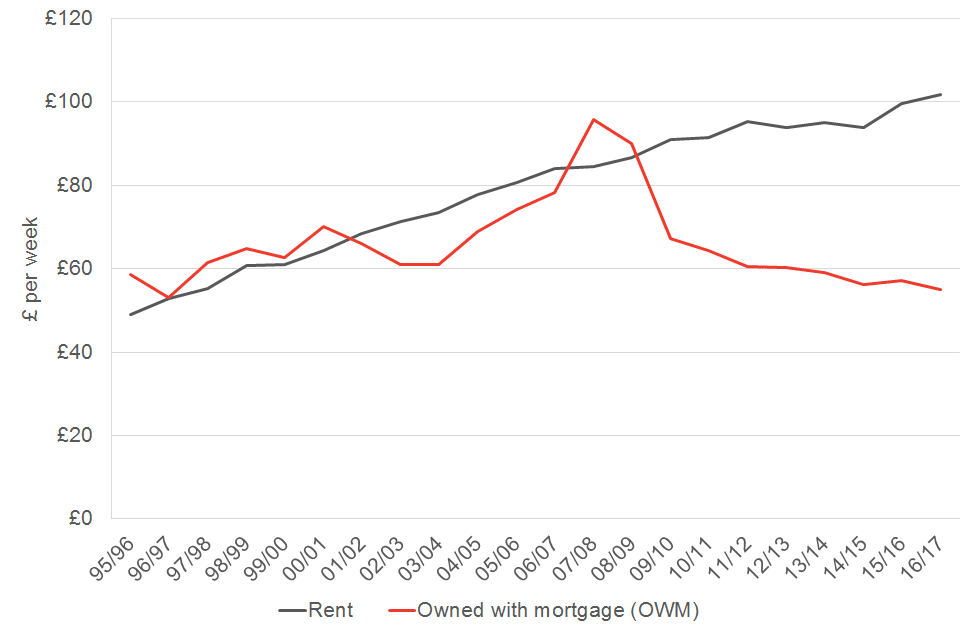

Renters in Scotland have seen housing costs increase by around 21% over the last decade in real terms. Meanwhile, housing costs for households owning with a mortgage have fallen sharply in just a decade, although this is primarily attributable to a spike in 2007/08 (Chart 1). Overall, homeowners with mortgages have seen their real costs decrease to levels seen twenty years ago.

Real equivalised mean housing costs in Scotland

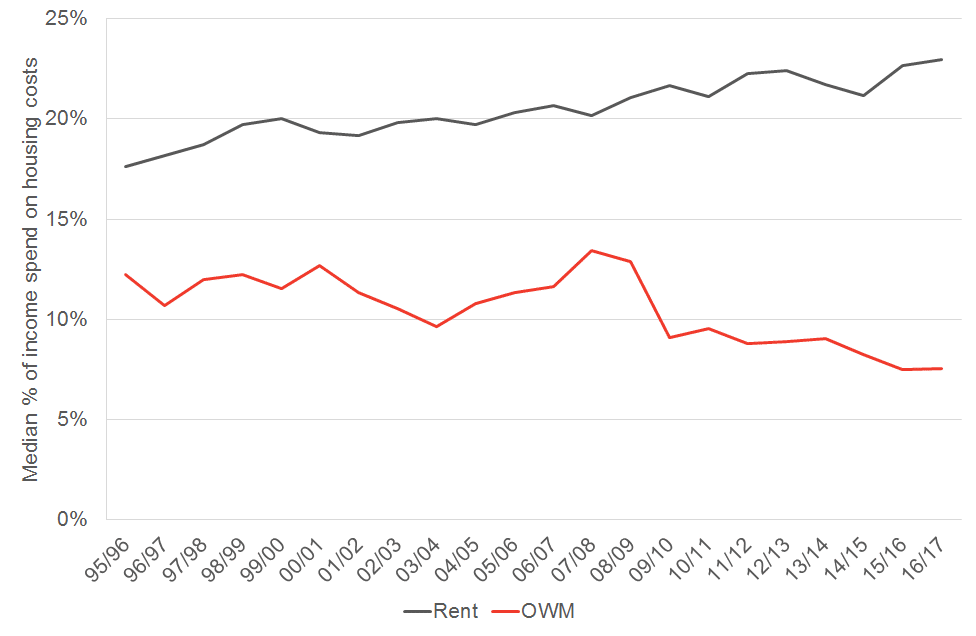

Of course, the impact of housing costs [1] are felt in relation to levels of household income. When housing costs are looked at as a percentage of income, those owning with a mortgage pay four percentage points less of their income on their mortgage than they used to (Chart 2). On the other hand, households renting pay five percentage points more of their income than 20 years ago on average.

Since this data comes from a survey, there will be an element of statistical uncertainty around these point estimates but the overall trends are clear in the chart below.

Percentage of income spent on housing costs by households in Scotland [2]

These higher rent costs can partly be attributed to an increasingly privatised rent sector. On balance, private renting is more expensive than social renting and has tripled in size to become the single largest rented sector in Scotland.

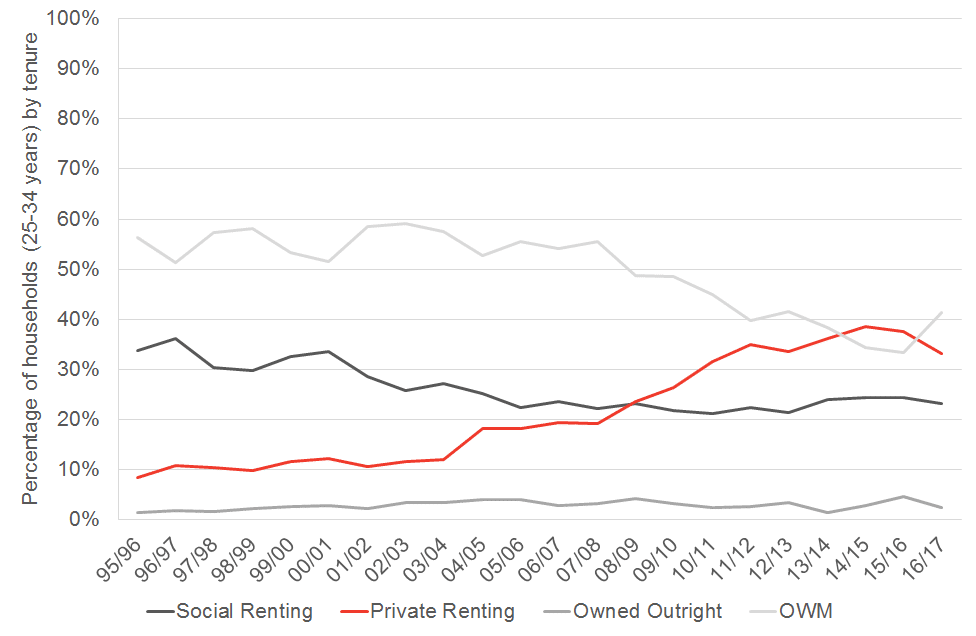

One effect of this has been the impact on young people. More young people are renting, and fewer owning their property, than ever before (Chart 3).

Tenure by type for 25-34 year old householders [3]

The two most noticeable changes here are in the percentage of 25-34 year old householders owning property with a mortgage and privately renting. While only around 8% of such households privately rented in 1995/96, this figure has moved to over 33% in 2016/17. Meanwhile, the percentage of those owning with mortgages has steadily declined.

So why are fewer young people owning property when there has almost never been a better time to be paying a mortgage? The main difficulty lies in buying a home – or at least being able to put down a deposit – in the first place. The deposit required to purchase with a mortgage has increased since the financial crash. The average first time buyer loan-to-value ratio was 90% in 2007, falling to 75% in 2009 and remaining fairly flat since 2014. In Q1 of 2016, first-time buyers paid a loan-to-value ratio of 83%, on average (Council of Mortgage Lenders).

In addition, as a result of interest rates being historically low, it is much more difficult to save for a deposit than in the years preceding the crisis. The historically low interest rates we have experienced since the economic crash has been good news for borrowers but the opposite for savers.

At the start of August, the Bank of England decided to raise the interest rate for only the second time in a decade from 0.5% to 0.75%. With interest rates still low, the difference this will make for people saving for their first home is likely to be negligible.

Help to Buy

To try to address this issue, the Scottish Government has introduced several schemes. For instance, the ‘Help to Buy’ shared equity scheme, which aimed to support buyers to purchase a new build home by providing a loan of up to 15% of the purchase price. So far, 12,820 homes have been purchased with support from the scheme. Unfortunately it is not clear to what extent the scheme has helped first time buyers or young people. While information has been sought by the Scottish Government on participating households, the completion of this information is not obligatory.

LBTT

Another initiative by the Scottish Government was changes to Land and Buildings Transaction Tax (LBTT), which replaced Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT). In 2015/16, a 0% rate on property worth up to £145,000 applied in Scotland versus £125,000 in the rest of the UK.

With the average house price in Scotland for first-time buyers of £115,776 in 2017, this would seem like a positive change in helping people to buy their first house (Land Registry, 2018). Despite this, the latest figures available from Revenue Scotland indicate that the number of residential transactions for houses with a purchase value of less than £145,000 has fallen by 7% between the introduction of LBTT in 2015-16 and 2017-18. Part of the reason for this decline may be to do with house prices increasing, pushing houses into the £145,000+ bracket.

Both the Office for Budget Responsibility and the Scottish Fiscal Commission have stated that First Time Buyer relief policies may simply displace other transactions and almost immediately be capitalised, ultimately raising prices (Office for Budget Responsibility, 2017; Scottish Fiscal Commission, 2017).

In December 2017, the Scottish Government decided to raise the zero-tax threshold further from £145,000 to £175,000 in 2018-19, giving up to a £600 relief for first-time buyers. Whether a £600 relief makes a difference to those considering buying their first home or not is up for debate.

Affordable Housing Supply

The Scottish Government launched the affordable housing supply programme in 2016, with an investment in low-cost home development and social and mid-market affordable rented accommodation. The target is to build 50,000 new homes by the end of the five years, of which 70% will be for social rent. The latest figures show that in 2016-17 and 2017-18, 15,870 units have been completed, of which 9,846 (62%) are for social rent (Scottish Government).

Overall, trends in housing indicate that people in Scotland, and particularly young people, still face challenges in terms of housing affordability and in owning their first home. Although the Government has taken some steps to improve this situation, there is a long way to go. With inclusive growth a key priority for the Scottish Government, it is important that young people don’t get left behind in terms of housing.

In a future article in the Fraser Economic Commentary, housing trends in Scotland will be expanded upon further and in relation to trends in the UK.

[1] Housing costs include rent; interest on mortgage repayments; building insurance; service charges; council tax and water and sewerage charges. Mortgage capital repayments are not included as these payments are considered to contribute to a household’s overall wealth.

[2] The mean percentage of income spent on housing costs is affected by households who have small or negative incomes. These are households who could be in debt, for instance, and result in some high figures when housing costs are calculated as a % of income. For this reason, the median percentage is used here.

[3] Age groups are defined by the age of the highest income householder

Analysis based on data from:

Department for Work and Pensions. (2018). Households Below Average Income, 1994/95-2016/17. [data collection]. 11th Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 5828, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-5828-9

Department for Work and Pensions, National Centre for Social Research, Office for National Statistics. Social and Vital Statistics Division. (2018). Family Resources Survey, 1994-2017. [data collection]. UK Data Service. SN: 8336, http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-8336-1

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.