For many, the big story of the Budget won’t be the tax and spending announcements of the Scottish Government but the forecasts for the Scottish economy published today by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC).

Recall that the SFC was established to provide independent forecasts of the Scottish economy following the passing of the Smith Commission powers. These are the official forecasts upon which the Scottish budget is based.

Their assessment of the outlook for the Scottish economy – if it turns out to be accurate – suggests a period of exceptionally weak growth for the next 5 years. Growth is projected to be below 1% each year to 2020/21 and only just above 1% by 2022/23.

Such trends in Scottish economic growth have not been witnessed in 60 years.

Like the outlook of the OBR for the UK as a whole, the SFC forecast that real household disposable income in Scotland will not see any growth before 2020-21.

Comparisons of forecasts

The SFC’s forecasts are more pessimistic both in comparison to the UK economic outlook (OBR forecast) and our own most recent assessment.

GDP growth forecasts: OBR (UK), SFC and FAI

| OBR (UK) | SFC | FAI1 | |

| outturn 2016/17 | 1.8% | 0.4% | |

| 2017/18 | 1.5% | 0.7% | 1.2% |

| 2018/19 | 1.4% | 0.8% | 1.4% |

| 2019/20 | 1.3% | 0.9% | 1.7% |

| 2020/21 | 1.3% | 0.6% | |

| 2021/22 | 1.5% | 1.0% | |

| 2022/23 | 1.5% | 1.2% |

[1] FAI forecast is for calendar years, so should be compared with caution with the OBR and SFC forecasts.

Whilst we are more optimistic about medium term growth prospects, the SFC’s forecasts are broadly consistent with our ‘low’ productivity scenario from our most recent commentary.

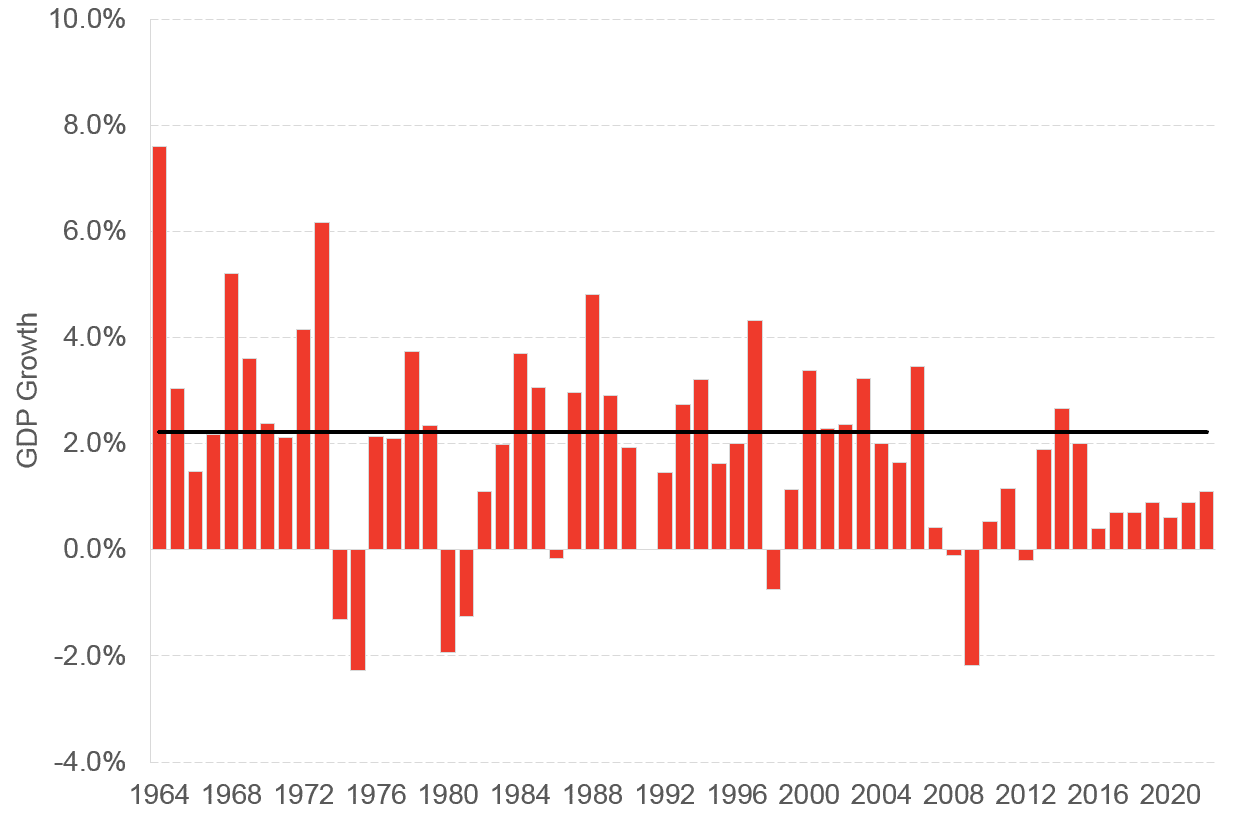

The SFC forecasts also suggest far weaker growth than the historical performance of the Scottish economy. Using the longest available Scottish GDP growth series (back to 1963) published by the Scottish Government, the average growth over the past 53 years was around 2% per year. Over the period from 1963 up to the Financial Crisis, average annual growth was 2.2%.

Chart 1 illustrates that if the SFC forecast turns out to be correct, over the next few years Scotland is on track to experience the longest period of below trend annual growth in almost 60 years.

Chart 1. Historical annual GDP growth in Scotland – black line = Scotland’s long-term growth rate average (since 1963)

Source: Scottish Government, FAI calculations

These forecasts come on the back of two years of data suggesting that the economy has been relatively weak. This suggests that the SFC see this weakness as being of a more structural rather than cyclical nature.

The major factors underlying this growth outlook are the SFC’s forecasts for continued weak productivity growth and a decline in the 16-64 population.

The outlook for productivity

As has been well documented, productivity growth has been poor in the UK since the financial crisis. In their November UK forecast, the OBR significantly revised down the outlook for UK productivity.

But the SFC are even more pessimistic than the OBR (see table below) forecasting Scottish productivity will be slower that in the UK in every year of the forecast.

| SFC | OBR | |

| 2018 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| 2019 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| 2020 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| 2021 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| 2022 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

The outlook for Scotland’s working age population

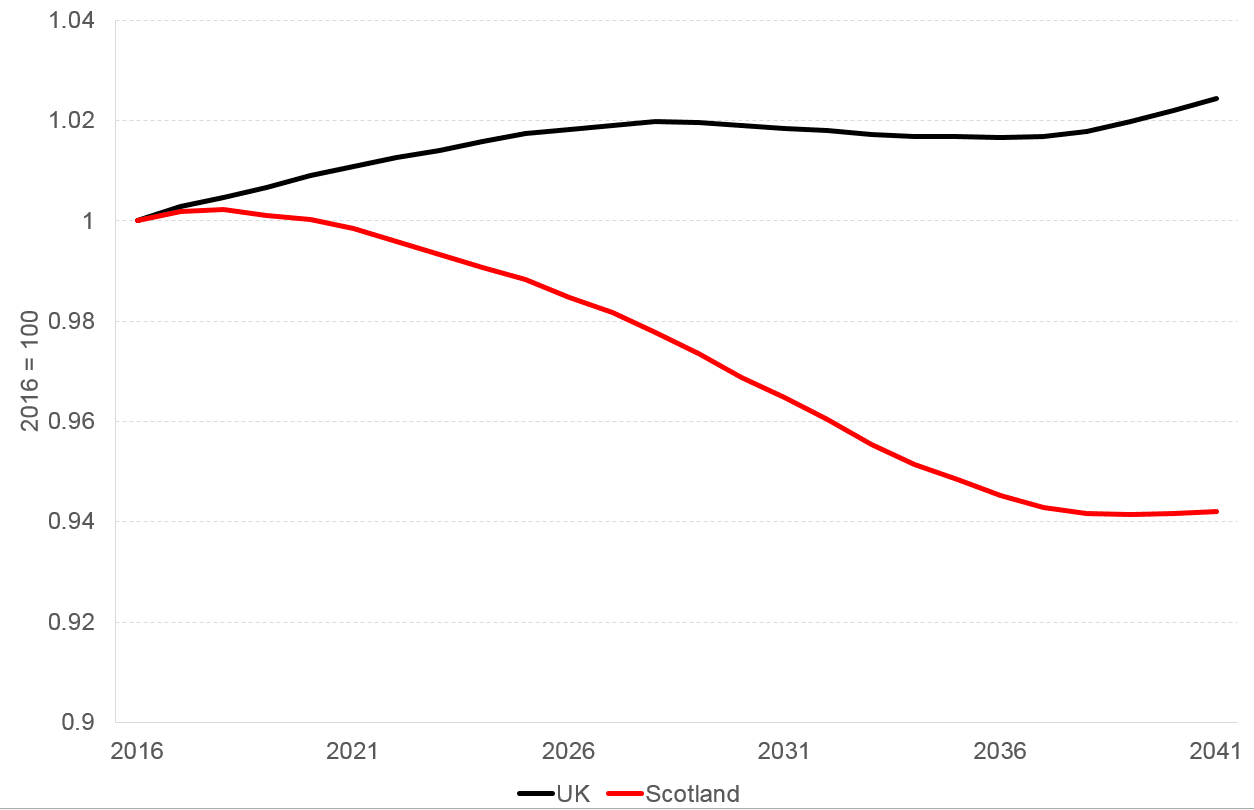

The other major source of the divergence between Scottish and UK growth is in the forecasts for the working age population growth (see chart 2).

According to the ONS population projections used by the OBR and the SFC in their forecasts, the Scottish 16-64 population is expected to start declining in 2019 and fall below 2016 levels by 2021. In contrast, the UK’s working population is expected to increase slightly.

Chart 2. Scottish and UK projected population aged 16-64

Source: ONS 2016-based population projections, Principal for the UK (used by the OBR), 50 per cent EU Migration Variant for Scotland (used by the SFC).

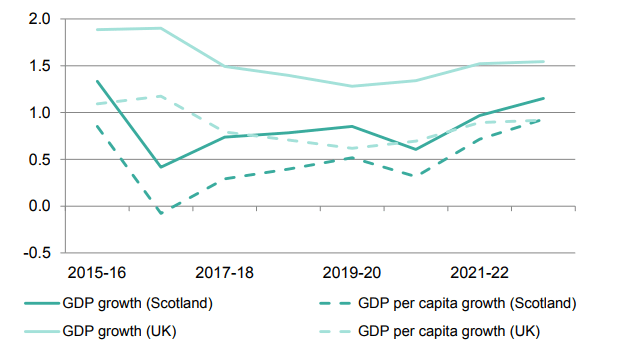

Growth in GDP per capita

In per capita terms, the gap in GDP growth between Scotland and the UK is still evident – although it is narrower than the gap for total GDP. GDP per capita comparisons control for differences in population growth .

The remaining gap will be driven by differences in productivity and also long-term labour market outcomes etc.

Chart 3. Forecast GDP and GDP per capita growth, Scotland as forecast by the SFC and UK as forecast by the OBR

Of course, under the Fiscal framework Scotland is protected from the impact on tax revenues of weaker population growth (at least until 2021). This illustrates why the Scottish Government were right to press for indexed deductions per capita as the methodology for adjusting the Block Grant (BGA).

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.