The shifting balance of economic activity from west to east is leading to fundamental structural shifts in our economy.

The growth in population, investment and job opportunities is displacing once traditional engines of growth with new ones. But these changes are bringing their own pressures, on public services and infrastructure.

You might think we’re talking about the global economy. We’re not, instead we’re talking about the Scottish economy.

Now this description is clearly over dramatic, but one interesting, but largely unnoticed, trend in the Scottish economy in recent years has been the distribution of growth across the country.

Edinburgh is the fastest growing city in Scotland and one of the fastest growing parts of the UK – with growth outpacing even that of London.

GVA per head in the City of Edinburgh was £44,250 in 2017, compared to a Scottish average of £25,500. Average annual workplace earnings are £38,500 for full-time workers compared to a Scottish average of £34,500, whilst the average price of a house is £265,000 compared to a Scottish average of £155,000.

Edinburgh has always been one of the most prosperous parts of the country. But since the Great Recession, the gap between Edinburgh – and Edinburgh region – with the wider Scottish economy has grown, with a sharp increase in the number of people living and working in the local area.

Whilst clearly a positive, the pace and concentration of growth is clearly putting pressure on local structures leading to fears in some quarters of the sustainability of such growth. At the same time, there are concerns that these changes may serve to amplify deep seated regional inequalities that already exist in our economy.

Central sources of economic activity

The concentration of economic activity within the east of Scotland, and in particular to Edinburgh, is becoming more noticeable.

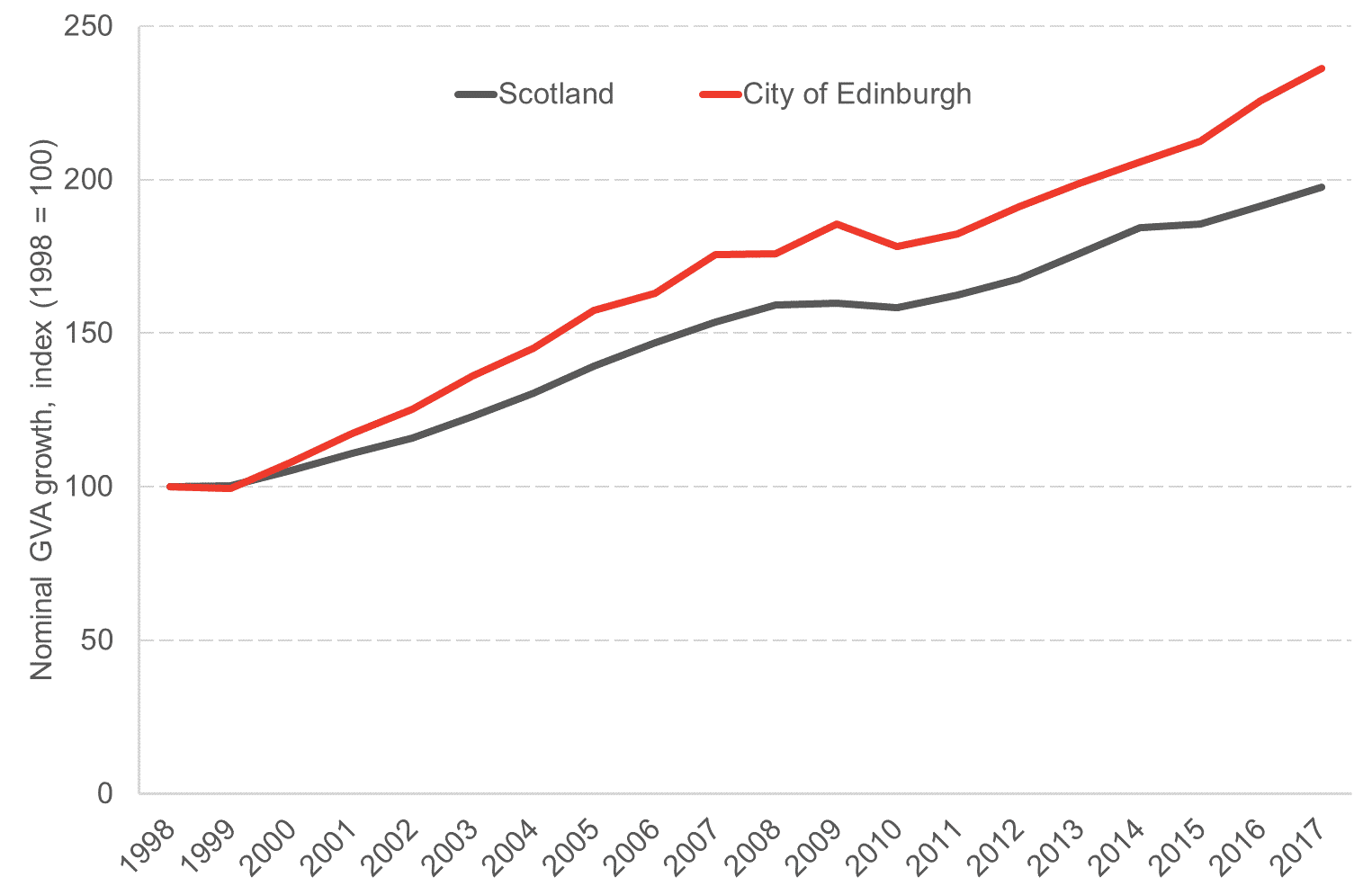

The following chart shows the growth performance of Edinburgh and Scotland as a whole since 1998.

Chart 1: Nominal GVA growth for Scotland and the City of Edinburgh, index (1998=100), 1998 – 2017

Source: ONS

The growth gap widened through the early 2000s, before closing during the financial crisis. What is striking is that whilst being particularly hard hit by the financial crisis – with RBS and HBOS at the epicentre of the banking collapse – the wider Edinburgh city economy has been remarkably resilient.

Since 2010, the growth gap has persisted and, if anything, has widened once again in recent years.

Over the past 20 years, nominal GVA per head growth in Edinburgh was 105%, exceeding Scotland’s growth of 85% and even London’s growth of 99%.

As a result, Edinburgh city’s share of Scotland’s GVA has risen from 13.7% in 1998 to 16.4% in 2017.

All of this builds upon an underlying performance which has led Edinburgh to be one of the most productive parts of the Scottish (and UK) economies. Indeed, for the most recent year that we have data (2017), Edinburgh’s GVA per hour worked was ranked 9th out of all UK NUTS 3 localities, and was the only non-London region in the UK top ten.

Resilient and fast-growing economies

It is not just in growth and productivity that Edinburgh has performed strongly.

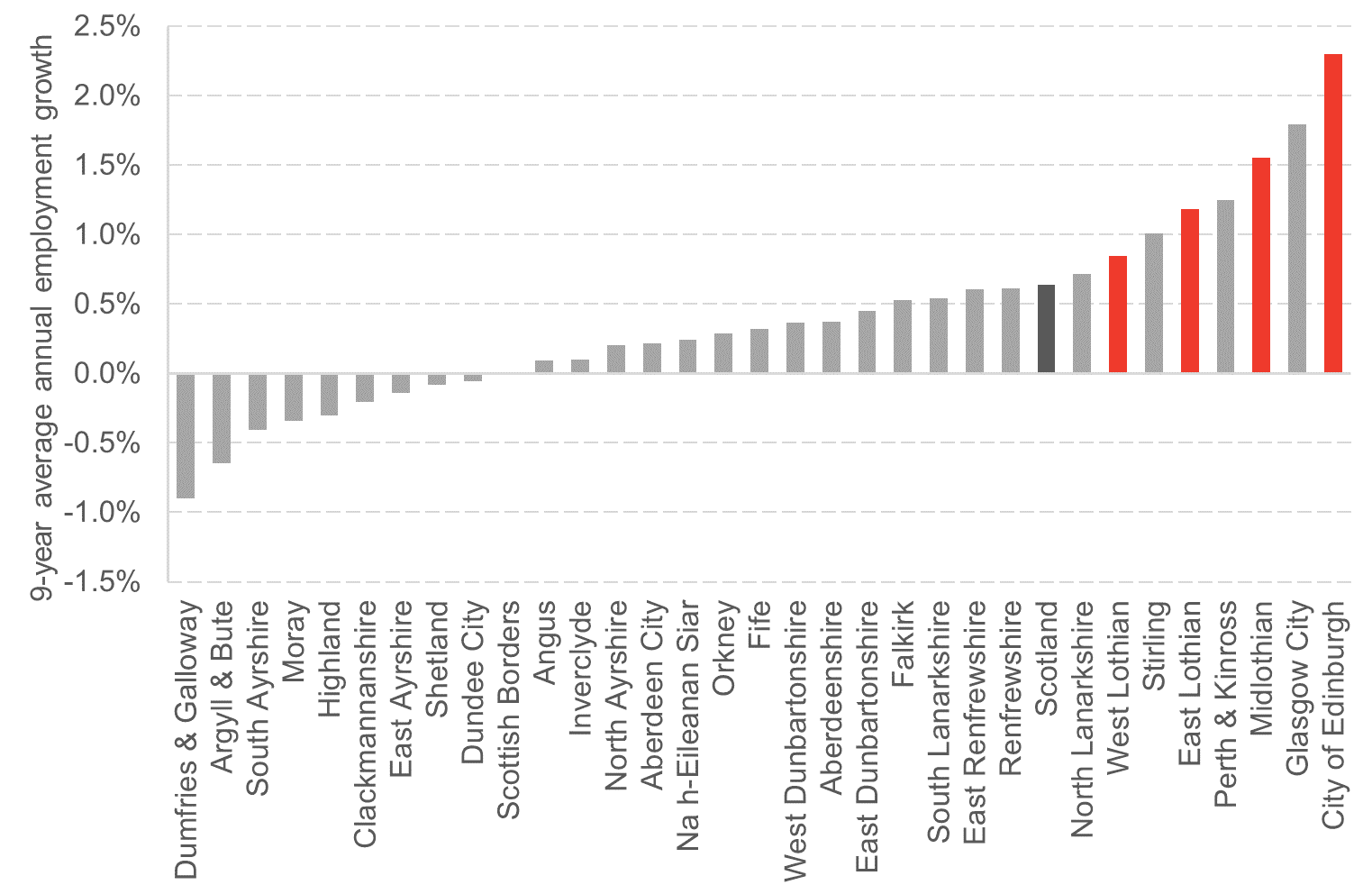

A decade on from the Great Recession and the resilience of the Scottish labour markets has been varied.

Since 2010, the number of people employed in Edinburgh has increased by 23% in Edinburgh compared to growth of 6% across Scotland as a whole.

Broadening out the regional focus, we see that local authorities in and around Edinburgh have been amongst the strongest performing areas in the country in terms of new jobs growth since the financial crisis. Average annual employment growth has been above the Scottish average in Edinburgh, Midlothian, East Lothian and West Lothian. See Chart 2.

Chart 2: 9-year average annual employment growth in Scottish local authorities, 2010-2019

Source: ONS, APS

In total, across Edinburgh, Midlothian, East Lothian and West Lothian, the number of people employed has jumped by 17%.

Employment in Edinburgh and the Lothians now makes up 18% of the Scottish total compared to 16% in 2010.

There are a number of reasons for this, in particular the steady growth in services industries (with manufacturing and construction lagging behind) where Edinburgh has a particular strength in. In Edinburgh, almost 90% of working age adults in employment work in services industries – that is, over 10 percentage points greater than Scotland overall.

If anything, the pace of employment growth appears to be accelerating.

Over the past five years, employment in Edinburgh has jumped by 15% – an extra 35,000 employed within the city boundary.

Expanding economies

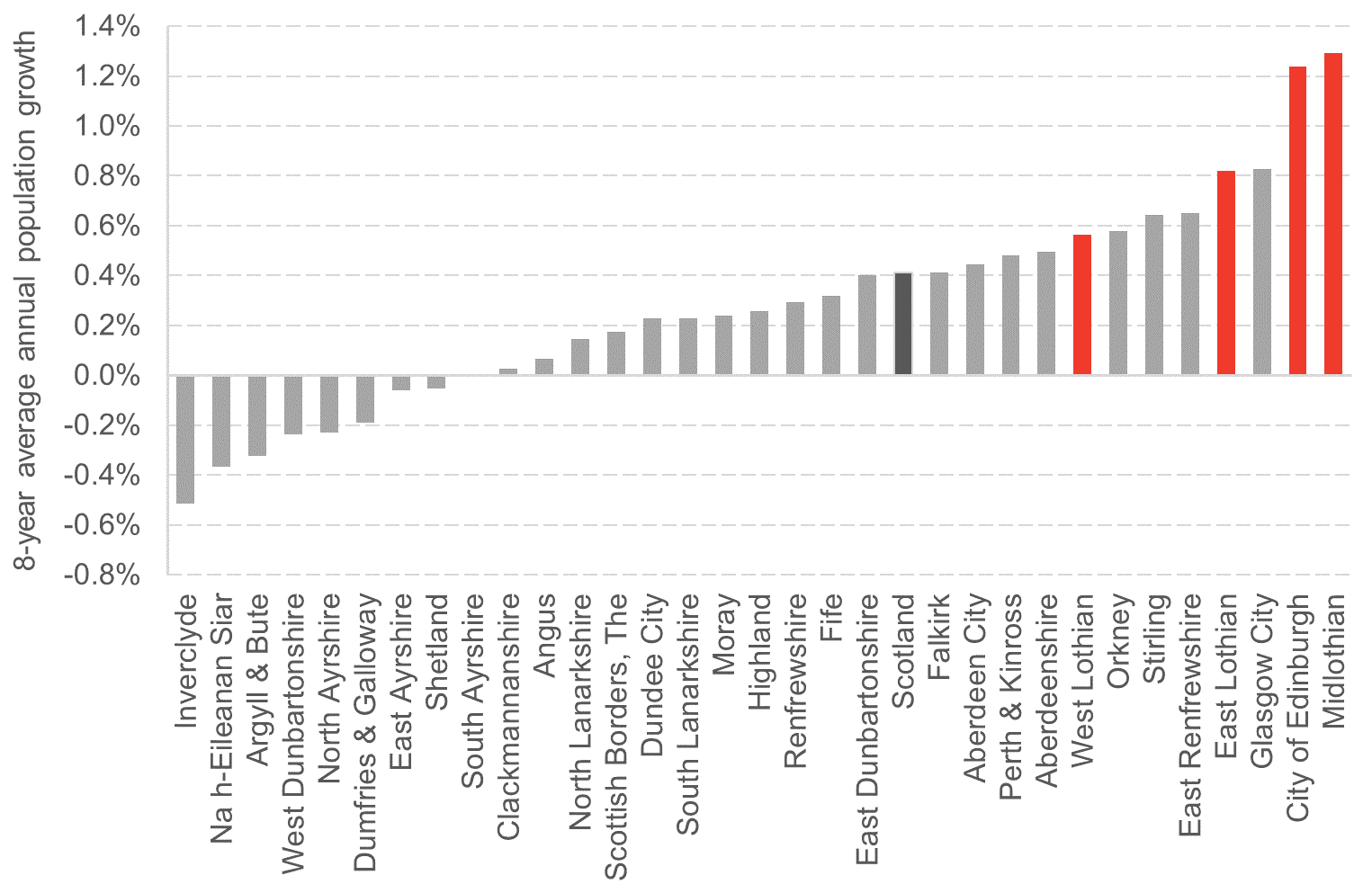

With such growth and labour market trends, it is no surprise that population growth has been on the increase.

Since 2010, Edinburgh’s wider region has experienced stronger population growth than the rest of the country. See Chart 3.

Chart 3: 8-year average annual population growth in Scottish local authorities, 2010-2018

Source: ONS

Since 2010, Edinburgh’s population has risen by almost 50,000. In Midlothian it has increased by 9,000, 6,500 in East Lothian and 8,000 in West Lothian

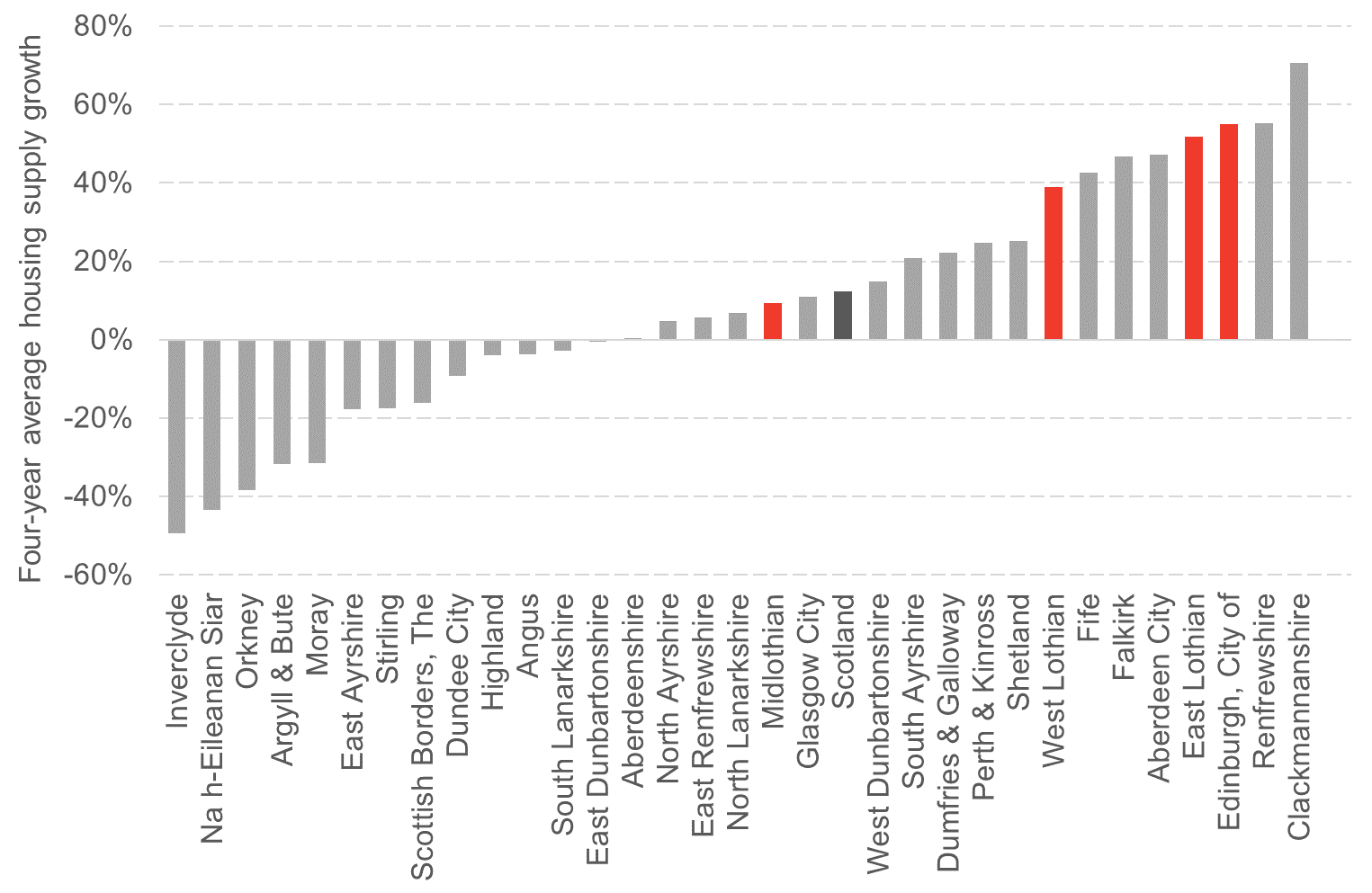

The growing economic activity in the east of the country is consequently driving housing supply growth in Scotland.

Housing supply in Edinburgh and the Lothians made up 14% of Scotland’s new housing supply in 2010-11 but 22% in 2017-18.

The population of these areas over the same time period has increased from 16% of Scotland’s total population to 17%.

Chart 4 shows the rate of growth in housing supply over the last four years (2014/15 to 2017/18) compared to the previous four years (2010/11 to 2013/14).

Chart 4: Four-year average growth in local authorities of Scotland’s housing supply, 2010 – 2018

Source: Scottish Government

The latest Property Market Report showed that, in 2018/19, Edinburgh accounted for over 65% of Scotland’s volume of residential properties that were sold for over £1 million.

Growing at such a pace has its own challenges.

It can put pressure on infrastructure and demand for public services, particularly if investment decisions do not keep up with the pace of growth in the overall economy. It also has the potential to widen inequalities not just nationally but also within Edinburgh (with the potential to create an ‘hour-glass’ economy).

Edinburgh Council has been particularly mindful of such issues, and aims to tackle this through its ‘Enabling Good Growth’ strategy. It has also been at the forefront of new initiatives to manage the pace of growth, for example in its tourism sector through the implementation of a new Transient Visitor Levy.

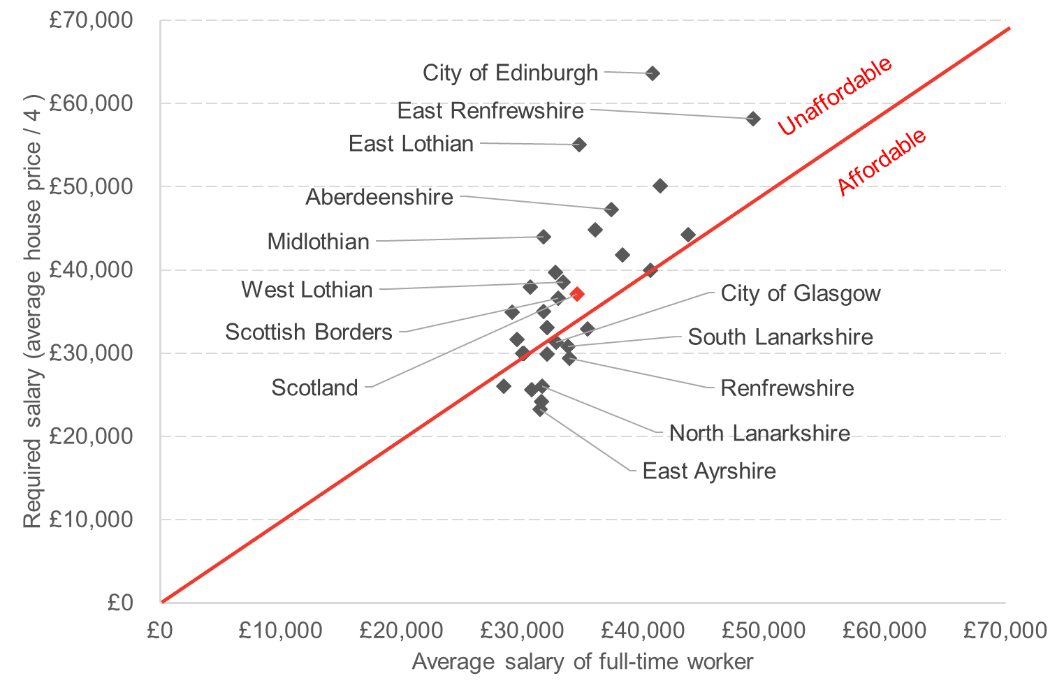

On area of concern is affordability of housing. Where despite wages being amongst the highest on average in Scotland, house prices are such that for many getting on the property ladder remains a major challenge. See Chart 5.

Chart 5: Housing affordability in Scottish local authorities, 2018*

Source: UK HPI, ONS ASHE *here we use resident earnings instead of workplace

Outlook

Most predictions are that this shift in the balance of economic activity to continue.

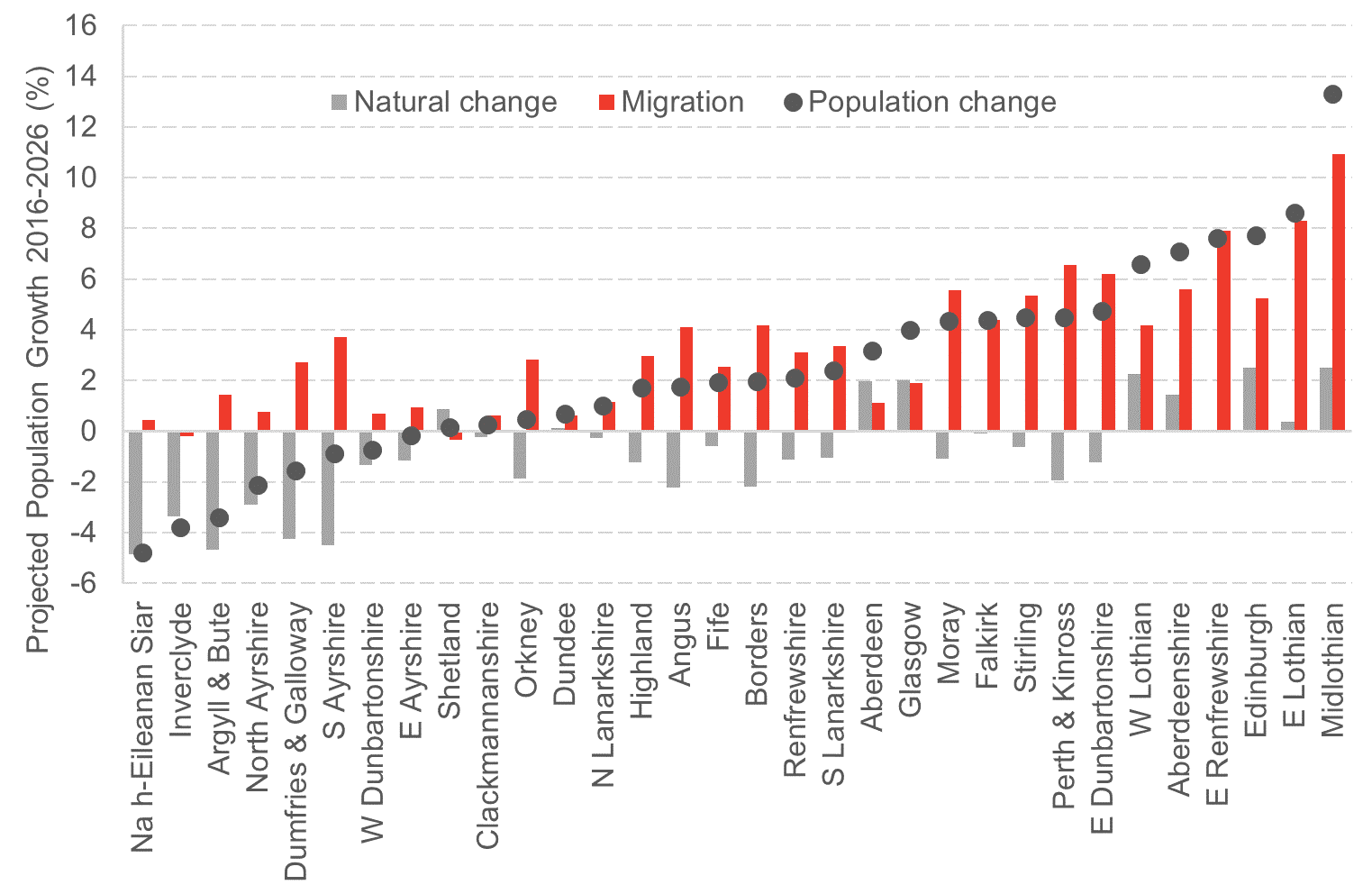

In particular, the demographic profile of the east of the country are much more favourable. This is not just driven by projected migration but also underlying natural change within the existing population base.

Edinburgh and the Lothians are projected to experience strong population growth in the years to come – Chart 6. For example, the population of Midlothian is projected to increase by almost 14% over the next decade.

Chart 6: Projected population growth in Scottish local authorities, 2016 – 2026

Source: National Records of Scotland

In recent years, the Scottish Government has emphasised the importance of ‘regional inclusive growth’. But current trends suggest that the gap between the strongest part of the Scottish economy – Edinburgh and its surrounding areas – and the rest of the economy might widen.

This poses a number of important questions for policymakers.

Should public support be targeted toward Edinburgh as an engine of growth across the entire Scottish economy? Or should investment and resources be shifted to weaker parts of our economy to help counterbalance some of the natural pull of Scotland’s capital?

Should the concentration of public servants be tackled by shifting jobs out of the capital to other parts of the country where demand is weaker and the cost of living is cheaper (as the UK has done in recent years with London)?

And should local policymakers be given more discretion to vary local policies to best support their particular challenges and opportunities?

Authors

Adam McGeoch

Adam is an Economist Fellow at the FAI who works closely with FAI partners and specialises in business analysis. Adam's research typically involves an assessment of business strategies and policies on economic, societal and environmental impacts. Adam also leads the FAI's quarterly Scottish Business Monitor.

Find out more about Adam.