Yesterday saw the publication of the latest Scottish Government official estimates of productivity in Scotland.

Headline results

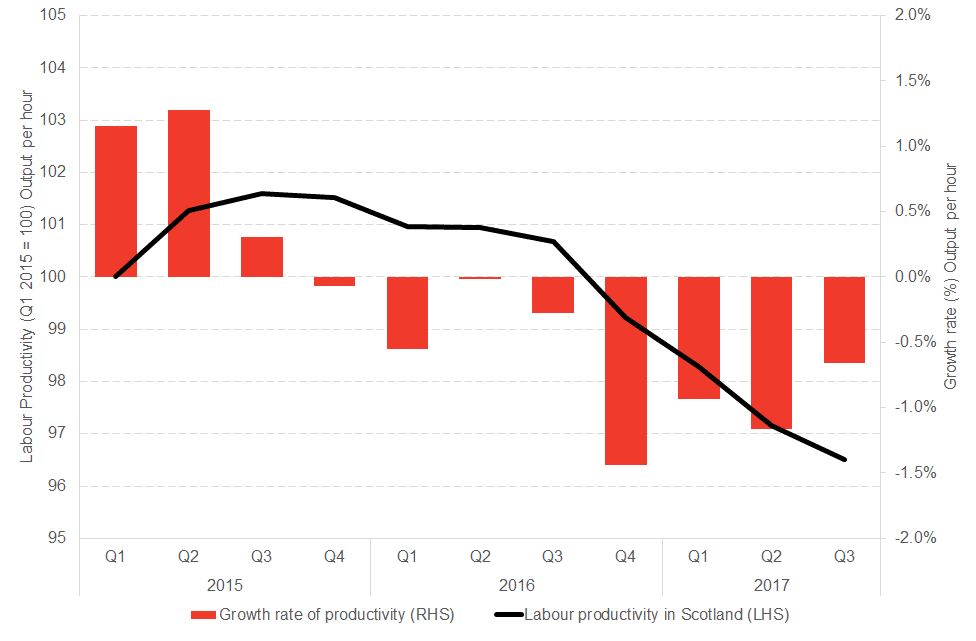

The latest figures show that labour productivity – as measured by output per hour – fell by 0.7% during the three months Jul-Sept 2017.

This was 8th quarter in a row of falling productivity in Scotland.

Chart 1: Productivity in Scotland: since 2015

Source: Scottish Government Productivity Statistics

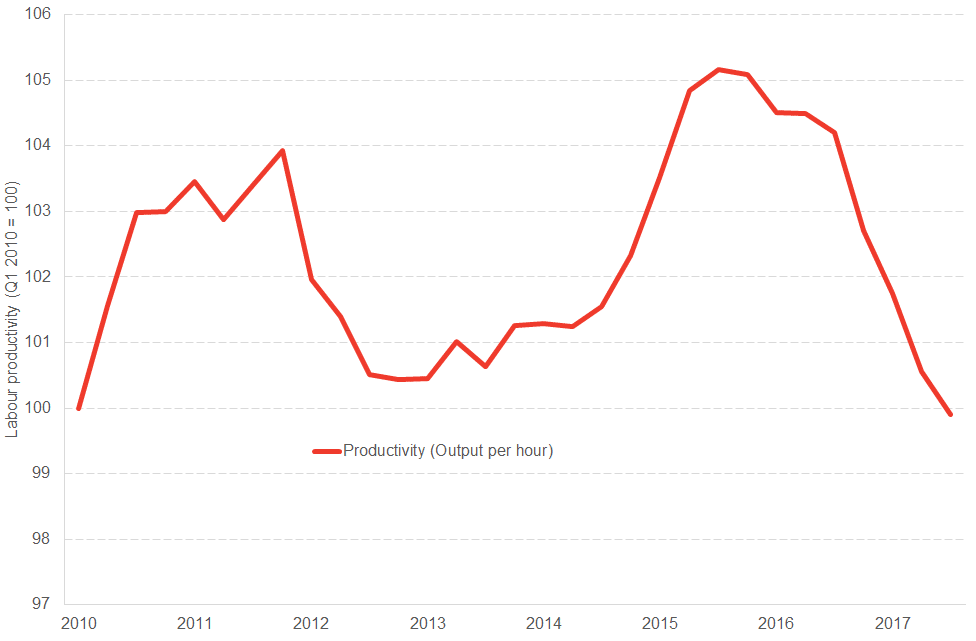

On this measure, productivity in Scotland is back at 2010 levels.

Chart 2: Productivity in Scotland: trend since 2010

Source: Scottish Government Productivity Statistics

Falling productivity = the cost of a strong labour market when output is weak

The continued weak performance of productivity in Scotland is not surprising given recent trends.

Labour productivity measures how well output is fairing relative to changes in how much labour is being used to produce that output. If we’re able to produce more for the same amount of hours worked then we are more productive. On the other hand, if we are working harder but not producing much more, then our productivity will fall.

As has been well documented, economic growth in Scotland has been weak now for the best part of two and a half years. In the 10 quarters since the start of 2015, Scottish GDP has risen by just over 1%. We’d normally expect growth to be double that in 12 months (or 4 quarters).

Against this however, the Scottish labour market has held up much better. Employment remains close to a record high, whilst unemployment has fallen from 6% at the start of 2015 to just 4% today.

Yesterday, the Scottish Government cited these labour market trends in response to the productivity figures as an illustration of the strength of Scotland’s economy. This is of course true. But unfortunately it is this very balance – more people in work but weak growth in output – that has driven the fall in Scottish productivity over the last two years.

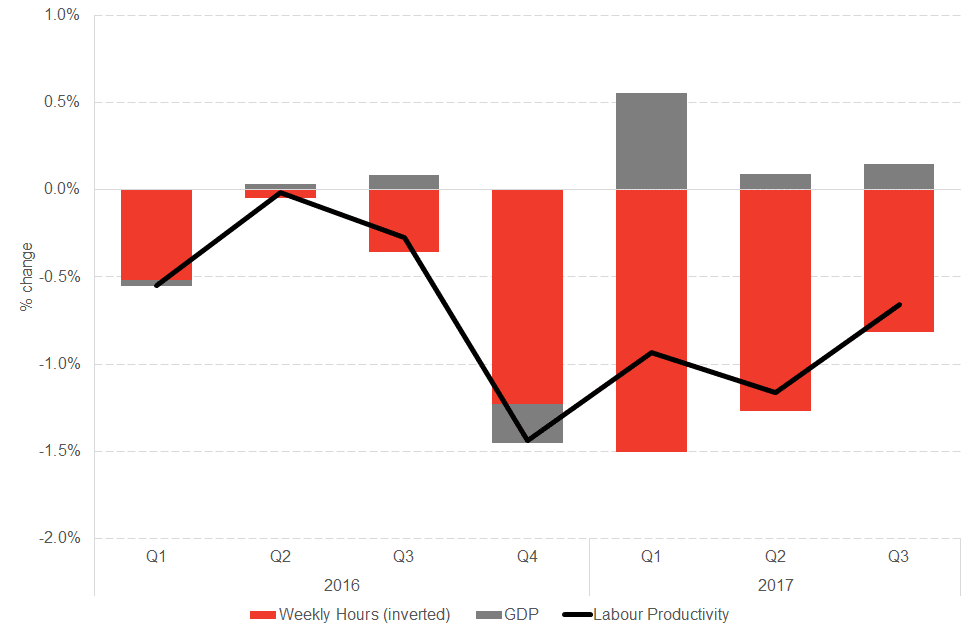

Chart 3 compares growth in the economy with the growth (inverted) in hours worked.

As an illustration, in Q3 2017, the amount of hours being worked in the economy increased by 0.8%, but this outstripped the growth of 0.2% in Scottish GDP. As a result, productivity fell by 0.7%.

Chart 3: Changes in hours worked and output in Scotland

Source: Scottish Government Productivity Statistics

Of course, on the one hand, it is preferable for people to be in-work rather than out of work. So increasing hours worked is a positive.

But if more people working is not helping to generate growth in the economy then it clearly is neither sustainable nor good for long-term prosperity. Indeed, a lack of productivity growth – as we have seen over the last decade – acts to squeeze the incomes of those in work.

More people might be in work, but they’ll be paid less, in less rewarding work and less likely to be fully utilising their skills or talents.

The risk is that this becomes a cycle. Firms continue to employ people but on relatively low pay; to afford this they invest less in technology, plant and machinery etc; which in turn leads to weaker productivity; lower earnings; less investment and so on.

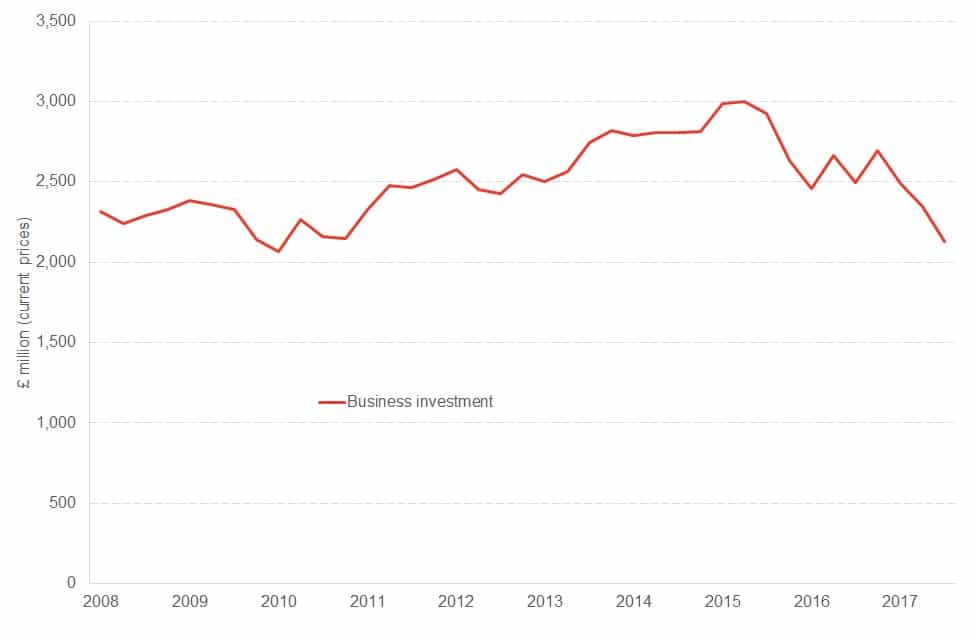

Figures last week show a fall of 15% in business investment in Scotland (in current prices) over the last year. Investment is a key driver of productivity over the long-term. But levels of investment have barely moved in 10 years – even before adjustment for inflation.

Chart 4: Business Investment in Scotland

Source: Scottish Government National Accounts

What can we conclude?

As we will discuss in a future blog, the series for Scotland is somewhat more positive when using ONS’ estimate of Scottish GDP as oppose to the Scottish Government’s own estimate. And many of the trends identified above are also borne out by what is happening at the UK as a whole.

But whatever measure or comparison used, it is clear that the challenge to boost Scotland’s long-term rate of productivity shows no sign of disappearing.

Back in 2007, the Scottish Government set a target to “rank in the top quartile for productivity amongst our key trading partners in the OECD by 2017”. It is clear that this target will be missed.

In many ways, should we be surprised?

Over the decade what has fundamentally changed – either in policy or business ambition – that would suggest that there has been a marked improvement in Scottish productivity?

Perhaps new ideas are needed, rather than new strategies or targets (of which there is always little to disagree on).

Two initiatives for 2018 offer some potential.

The hope of many in policy circles is that the new Strategic Board for Enterprise and Skills, might not only offer some new insights on how to better utilise public money in boosting productivity growth but that it might help encourage policy makers to take difficult choices. Some will argue that Holyrood does not have all the levers to support the economy, but with £2.4bn of spend each year on enterprise and skills in Scotland, not to mention business rates and wider spending on infrastructure, the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government clearly have many levers at their disposal. It’s not clear how bold the new board intends to be, but at the very least an evaluation of where the public sector is targeting its spend – and whether these policies are having the desired impact and/or value for money – would be a good start.

At the same time, the David Hume Institute – supported by the new Scottish Policy Foundation – are looking at new ideas to boost productivity in Scotland and to learn from the experience of other countries.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.