Last week the delayed second year child poverty progress report, due under the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017 was published. This statutory report has two required elements: firstly, to assess progress towards meeting the child poverty targets (aka never seen before reductions in child poverty to all but eradicate it) and secondly to report on progress made in implementing policies set out in the ‘relevant’ delivery plan – in this case this refers to the 2018 ‘Every Child Every Chance Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan 2018 – 2022’.

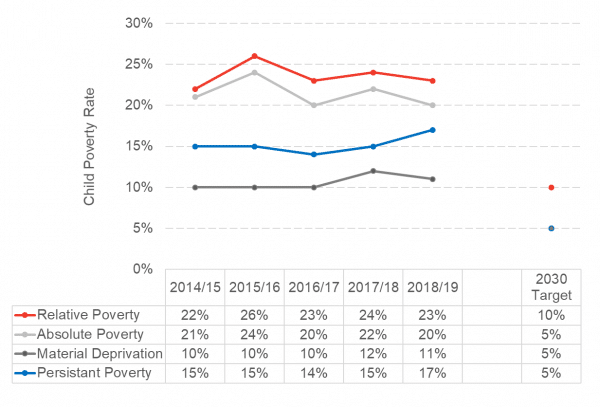

Putting any frustration at the delay in the report aside, there is progress being made on many of the promised policies set out in the 2018 delivery plan. Three out of four of the target measures of child poverty have fallen in the year 2018-19, albeit it only slightly. Scottish Government statisticians will be quick to remind anyone who will listen that this data is often volatile from year to year and a number of years’ worth of consistent data will be needed to determine if the trend is indeed downwards. However, the fact that these figures haven’t increased as was widely expected due to the impact of UK Government welfare reform measures such as the two-child limit is a relief.

Chart 1: Child poverty rates and targets

Source: Scottish Government analysis of HBAI and Understanding Society data

The (also delayed) Scottish Child Payment is now planned to be available for under sixes ‘from the end of February 2021’ with applications opening ahead of that in November. However, there is no sign that the Scottish Government has yielded to numerous stakeholder calls for some interim cash for families (which we also wrote about back in May) to support incomes now. Looking beyond social security, the progress report also notes the launch of a ‘Parental Employability Support Fund’ and the building of more affordable homes amongst and a range of other policies that should help the poverty figures move in the right direction.

This report gives us evidence of action. It may have taken a while, but there is money being (or soon to be) spent on tangible policies that will have an impact on child poverty.

But what size of impact? And is it enough to meet the targets?

Unfortunately, we don’t know the answer to those questions as there isn’t the capability to predict or measure the impact of many of the policies in the 2018 delivery plan, particularly those that don’t involve direct cash transfers (which are relatively easy to model).

We have reported before on the lack of evidence – both on expected impact and monitoring of impact, as has the Poverty and Inequality Commission. This isn’t due to lack of calibre of the civil servants on the front line of this work, but it does call into question the extent to which robust appraisal and evaluation are valued by the Scottish Government as a routine part of the policy making process. Even areas where monitoring and evaluation is in train, the link to child poverty is often not made. Monitoring and evaluation of whether policies, such as employability or housing, are having an impact on children in poverty needs to be built into policy development at the start, so the right systems for collecting and analysing data are put in place.

This leaves us in a rather unhelpful place. Whilst we have official statistics for the first year of the Child Poverty Delivery Plan (2018-19) we don’t know what impact any of the Scottish Government’s policy had on any of the four target measures in that year. We therefore don’t know if any of it is working as expected meaning making the policy ‘cycle’ more of a policy ‘dead end’ rather than a process of continuous improvement.

This analytical black hole is a big problem, and although efforts are being made to remedy this with appraisal modelling and evaluations being retrofitted into the space, the massive curve ball of a pandemic induced recession has thrown even more uncertainty where there was already plenty.

We are around 18 months away from the next Child Poverty Delivery Plan. This is the time to be starting policy development for implementation for the next delivery plan period, with the foundations set out for evaluation to inform the next delivery plan after that.

With election in between now and then, it is not going to be straightforward to get the attention needed on analytical issues – it’s hardly going to make it onto the front page of manifestos. Hopefully, behind the scenes, lessons have been learnt and the challenge of meeting the child poverty targets is now front and centre in policy development across government.

Without this, hopes of meeting the child poverty targets will be more down to chance rather than robust evidence-based policy. Given what is at stake, that is too much to gamble on.

Authors

Emma Congreve is Principal Knowledge Exchange Fellow and Deputy Director at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Emma's work at the Institute is focussed on policy analysis, covering a wide range of areas of social and economic policy. Emma is an experienced economist and has previously held roles as a senior economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and as an economic adviser within the Scottish Government.