Last week, we had the first set of income tax reconciliations for Scotland’s new fiscal framework.

For the coming year, that reconciliation figure will be around £200m.

In the aftermath of the publication of these figures, there were reports that Scotland was also in receipt of a £700m ‘bail-out’ from Westminster.

Is this accurate? In a word, no.

To be fair, it’s not hard to see how such a conclusion could be made.

A Treasury press release made clear that – in their eyes – the shortfall in Scottish income tax revenues was being offset by higher UK Government funding.

Now from a strictly spreadsheet perspective, this may be one very roundabout way of trying to explain how the fiscal framework works. But –

- There is no actual ‘increase in funding’. Instead, it’s an ex-post accounting adjustment within how the framework operates.

- This £737m figure has nothing to do with the Scottish Government’s relative tax shortfall – it is down to i) better HMRC tax data and, ii) weaker rUK NOT Scottish income tax receipts compared to forecast.

- The use of the phrase ‘additional UK Government funding’ has clearly created confusion. What is being talked about here is the block grant adjustment (BGA) – i.e. how much the UK Government is to be compensated for as a result of Scottish income tax revenues no longer flowing to the Treasury.

In essence, there was an overestimate of what should have been deducted for this purpose, whilst protecting the integrity of the Barnett formula. This has been amended. We’re puzzled why the UKG chose such language, particularly given the way it has been subsequently interpreted.

A quick recap: the fiscal framework

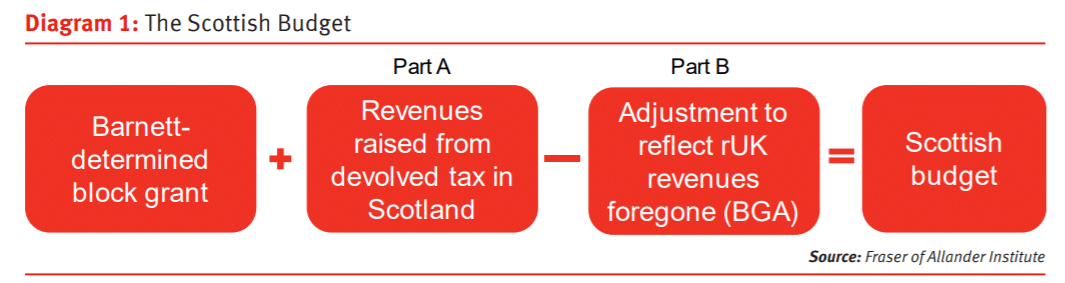

Under the fiscal framework, the Scottish Government’s block grant continues to be determined by the Barnett Formula. Barnett allocates to Scotland a population share of changes in ‘comparable spending’ in England.

But the block grant is now adjusted to reflect tax devolution – if not, Scotland would continue to receive the full block grant AND the devolved tax revenues (part A).

So the block grant is reduced by an amount each year (part B). How is this Block Grant Adjustment (BGA) calculated? It consists of two elements: an ‘initial deduction’ and an ‘indexation mechanism’.

The initial deduction is the revenue raised from income tax in year 1 of tax devolution (2016/17).

From then on, the indexation mechanism provides a measure of the rate at which ‘comparable revenues’ have grown in rUK. So in short –

- If rUK revenue growth slows, the BGA will grow more slowly;

- If rUK revenues grow pick-up, the BGA will grow more quickly;

The aim is to make Scotland ‘no better or worse off’ from tax devolution, provided it follows a similar tax policy to the rest of the UK and both economies perform in line with each other.

So what are the reconciliations on this occasion?

Before each budget, we don’t know how much Scottish or rUK taxes (for the BGA) are going to raise. So a forecast has to be made. Once outturn data is known, there is an adjustment – or reconciliation – according to whether or not these forecasts turned out to be higher or lower than outturn.

Last week’s reconciliations relate to how well the forecasts for 2017/18 have performed.

Scottish revenues were lower than what was originally forecast in Feb 2017 to the tune of £940m – Table 1. But the BGA is also now thought to be lower than originally forecast by £737m – Table 2.

The net impact is £204m – Table 3.

| Table 1: Scottish Income tax Reconciliations | 2017-18 (£m) |

| Scottish income tax: Initial forecast (prior to 2017-18 budget year) | 11,857 |

| Scottish income tax: Outturn | 10,916 |

| Scottish Income Tax Reconciliation effect | 941 |

And

| Table 2: BGA Reconciliations | 2017-18 (£m) |

| BGA: Initial forecast (prior to 2017-18 budget year) | 11,750 |

| BGA: Outturn | 11,013 |

| BGA Reconciliation effect | 737 |

| Table 3: BGA Reconciliations | 2017-18 (£m) |

| Net reconciliation (941 – 737) | 204 |

So, it is this £737m that is the source of the ‘bail-out’ claim.

But reflect on what this actually is.

The OBR originally thought that Treasury had to take out £11.75bn from the Scottish block grant to compensate the UK Government for no longer having control over Scottish income tax revenues (and to make Scotland ‘no better or worse off’).

We now know that this was too high so instead they are only taking out just over £11.01bn.

Moreover, this £737m revision has nothing to do with relative Scottish tax performance since income tax was devolved –

- A technical adjustment to reflect that HMRC now have better information on taxpayers in Scotland. Prior to devolution there was only ever an estimate. Now with actual income tax data, HMRC now think that Scotland’s tax base is about £500m smaller than first thought. But as this is an adjustment to the baseline, this reduction comes off both the BGA and Scottish income tax revenues (tables 1 and 2); and,

- Lower outturn data compared to forecast for rUK income tax receipts – NOT Scottish income tax receipts. Outturn data for income tax receipts across the UK – for various reasons – was lower than forecast (i.e. worse).

So to argue that Scotland has been ‘bailed out’ to the tune of over £700m because of a slump in the Scottish economy is clearly wrong.

And the use of the phrase ‘additional funding’ is odd.

If the exact opposite scenario was to occur next year – i.e. outturn data for both Scotland and the rUK happened to turn out ahead of forecast – can we expect a similar press release titled ‘Pick-up in Scottish income tax revenues offset by UK Government funding cut’?

Yes, there is a reconciliation gap to the tune of £204m that Scottish Government now needs to manage (not to mention potential further negative reconciliations in the future), but that’s it.

Final thoughts

One of the key challenges with the new fiscal framework is its complexity.

The onus must be on both governments to articulate how the framework is operating, the various changes from year-to-year and any risks, in a straightforward and transparent manner.

The risk of not doing so – and seeking to score political points at every turn – is that confidence in the underlying process of fiscal devolution could be eroded.

There are legitimate issues to be discussed about the Scottish budget, including the performance of Scotland’s tax base; the Scottish Government’s long-term fiscal strategy; and the adequacy of its tools to manage fiscal risks.

Searching for phantom ‘bail-outs’ is not one of them.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.