Social security has become a priority for the Scottish Government following the devolution of certain social security benefits and powers through the Scotland Act 2016.

This allowed the Scottish Government to introduce new benefits, change the process for devolved benefits, and ‘top-up’ UK benefits – powers which the Scottish Government have made substantial use of.

In this article, we discuss trends, risks, and forecasts in social security spending.

If you want to understand the basics of how social security works in Scotland, check out our overview here.

Trends in Spending

Scotland is spending a rapidly increasing amount on social security.

Devolved social security makes up around 10% of the Scottish Budget in 2023-24, up from 7.5% in 2017-18.

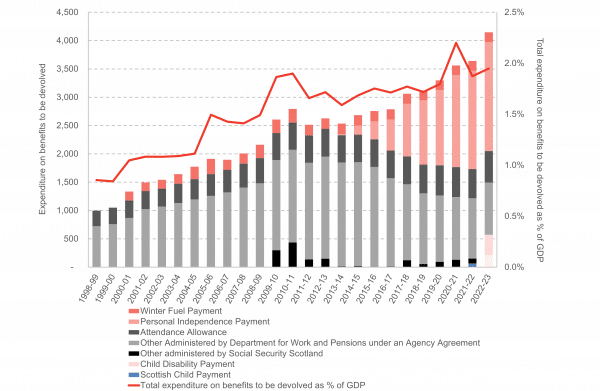

In cash terms, the amount paid out in devolved social security benefits has increased by over £1 billion in the past five years, from £3 billion in 2017-18 to over £4.1 billion in 2022-23 – growing at an annual average of 6.9%. See Chart 1.

Chart 1: Devolved Social Security Expenditure (as of Scotland Act 2016), £ million, 1988-89 – 2022-23 [1]

Source: Scottish Government, FAI Calculations, 2023

So, what’s driving this increase in spending?

A big chunk of the increase in cash terms comes from uprating for inflation and population growth. For example, in the 2023-24 financial year benefits received a 10.1% increase (in line with the September 2022 CPI rate). This added £433 million to spending in 2023-24. The Scottish Government will announce on 19 December what policy in this area will be for 2024-25, but in the absence of any statements indicating a new policy, it would be reasonable to assume the same uprating policy will be in place this year – which would also match what the UK Government announced in the Autumn Statement. This will mean uprating benefits by 6.7%.

The remaining part of the increases can be explained by the introduction and expansion of devolved social security programs administered by Social Security Scotland. Some benefits are still in the process of being transferred from the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) to Social Security Scotland, such as Winter Fuel Payments which have just been fully operationally devolved from next year onwards.

Most (over 80%) of the increase in social security spending over the past year is focused on two benefits:

- Adult Disability Payment (ADP) and Personal Independence Payment, increasing by £642 million and

- Scottish Child Payment, increasing by £216 million.

The Scottish Child Payment is a new social security program, launched in February 2021, and is expected to increase from £56m in 2021-22 to £442m in 2023-24 – £80m higher than initially forecasted in December 2021. This is because eligibility was extended to include all children under 16 in low-income families and the increase in the weekly payment rate from £20 to £25.

Some modelling suggests it could lift around 50,000 children out of poverty in 2023-24. It’s the flagship policy for meeting statutory targets to reduce relative child poverty to 10% by 2030, so it is clear why the Scottish Government are spending a large chunk of the budget on it.

The ADP is Scotland’s replacement for the main disability benefit for people of working age, namely the Personal Independence Payment (PIP). Launched in August 2022, the shift from the DWP to Social Security Scotland is ongoing and expected to take two years.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission anticipates higher spending on ADP due to the “friendlier” application process, which is likely to lead to more claimants. It is forecasted that the caseload will increase from around 420,000 in 2023-24 to 660,000 in 2028-29.

However, these estimations are quite uncertain, as we are not yet sure how many people will successfully take up this benefit.

Another reason for the increased caseload is because there is growing demand for disability payments across the UK.

While the reasons for this aren’t yet fully clear, the SFC and the Institute for Fiscal Studies point to increasing NHS waiting times, economic inactivity due to ill health, and people being more likely to seek support in response to the rising cost of living. All of this drives higher caseloads and puts additional pressure on spending.

This trend is expected to add £60 million to spending in 2023-24, reaching £223 million in 2027-28. But, since this trend is happening nationwide, it could also mean increased funding provided by the UK Government.

Risks in Managing Spending

The main risk that the Scottish Government faces is the difficulty in managing a demand led program through a fixed budget for social security spending.

The UK government adjusts the Barnett formula allocation to fund social security provision in Scotland at UK rates, but the Scottish Government has widened the scope of existing payments and introduced additional payments, such as the Scottish Child Payment.

This means that gap between what is spent on devolved social security compared to the funding provided by the UK Government continues to grow: a negative net position. See Chart 2.

Chart 2: Social security net position and new payments, Scotland, 2022-23 – 2027-28 (as of May 2023)

Source: Scottish Fiscal Commission, 2023

In other words, social security spending is due to increase significantly over time for two main reasons; firstly, the ‘friendlier’ system leading to higher take-up, and secondly, the introduction of new benefits (such as Scottish Child Payment) that the UKG Block Grant doesn’t account for, so therefore have to be funded from elsewhere in the budget.

This means a growing wedge between the money transferred from UKG through the Block Grant for spend on devolved benefits in England and Wales, and the amount actually spent in Scotland – resulting in a negative social security net position.

Medium Term Outlook

The SFC forecasts that social security spending will reach £7.8bn in 2028-29 – making up 13% of the forecasted budget. In real terms, the SFC expects more than £6.5bn to be spent on social security in 2027-28 in real terms, compared to £4bn in 2023-24.

These increases are largely driven by a larger number of recipients and an increase in benefit rates caused by forecasted inflation, as well as a larger number of devolved benefits – as outlined above.

Chart 3: Social security spending forecasts, December 2021, December 2022, May 2023

Note: 2021-22 reflects outturn data, 2022-23 to 2026-27 reflects forecast data

Source: Scottish Fiscal Commission, 2023

Chart 4 shows the breakdown of social security spending for 2021-2022 compared to 2027-28. Notably, Adult Disability Payment stands out as the program with the most significant spending increase. This partly reflects people being transferred across from the DWP to Social Security Scotland for this benefit over the next two years.

Yet, the SFC has pointed out the high level of uncertainty associated with this estimate. This uncertainty arises because Adult Disability Payment operates on a demand-driven basis, and we’re not sure about the exactly how many people will qualify or take-up this benefit.

This uncertainty highlights a challenge for the Scottish Government: managing a program driven by demand within the constraints of a fixed budget for social security spending.

Chart 4: Social security spending by benefit, 2021-2022 vs 2027-28 [2]

Source: Scottish Fiscal Commission, 2023

In 2022-23, the total amount needed to fund social security commitments above and beyond the amount of social security funding in the block grant was £374m; next year, it will be £776m, and in 2027-28 SFC estimates it will reach £1.4bn.

These amounts must be funded by the Scottish Government out of revenues beyond the block grant.

The Scottish Government has repeatedly asserted their commitment to a ‘human rights based’ approach to social security – and some evidence so far suggest that this approach is benefiting poorer households.

However, the less-than-upbeat forecasts pose some increasingly important questions about what measures will be required to fund the planned social security spending. In the context of tight budgets, the scope for any further change may certainly be limited.

Footnotes

[1] 2021-22 reflects outturn data, 2022-23 to 2026-27 reflects forecast data.

[2] Not shown in the chart (and under £40 million expenditure) – Scottish Welfare Fund, Employability Services, Best Start Foods, Best Start Grant, Funeral Support Payment, Severe Disablement Allowance and Child Winter Heating Assistance

Authors

Brodie is a Knowledge Exchange Associate at the Fraser of Allander Institute.

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.