This essay, written by Xiaoxuan Sha, was awarded second place in the 2021/22 Economic Futures Essay Competition. Students were invited to write an essay on an Economics topic related to the climate crisis and climate change policy in Scotland. Each of the four winning essays were featured as a perspective in the March 2022 edition of the FAI Economic Commentary.

Scotland in Climate Change time: an analysis on policies and opportunities in transportation, forestry and agriculture

Introduction:

Scottish government have set ambitious climate targets with a statutory requirement to achieve a 75% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and net zero by 2045, 50% of energy demand across electricity and transportation to be made up of renewable energy. This has been bashed on by Climate Change Committee, who pointed out the lacking of detail and clarity in the framework the government proposed.

Here we are going to investigate the effectiveness of potential policies by comparing existing research on climate change related policies and evaluating how they would fit in Scotland’s current situation. We mainly focus on analysing the challenges faced by two biggest contributors to Scotland total greenhouse gas emissions, domestic transportation and agriculture and the opportunities brought by the most effective role in absorbing carbon emission – forest.

New way to travel:

Domestic transportation takes up 36% of the annual greenhouse gas emissions, being the biggest contributor of carbon emission among all other sources. In addition to the government investment in public electric transportations, Scottish government has planned to spend £90 million on electric vehicles charging infrastructure, while 52% of the Scottish younger drivers hold doubt on buying or switching to EVs. Expansion of EV charging station would also bring intangible value such as reducing range anxiety and establishing confidence in the future of EV market. While the subsidising plan didn’t change, will this investment lead to desired outcomes? According to an experiment in Norway, it is calculated that an increase of the local electric vehicle ownership by 200% over 5 years with an additional electrical charging point in the rural areas of Norway. While another experiment in Germany identifies a long-run positive relationship between charging infrastructures and monthly EV registrations on a low scale, which means consumers may not react immediately or strongly to the increase in charging points considering charging speed and other factors. Both models used produce robust results, giving us confidence in the policy of further investment in charging infrastructure and the ultimate goal of transforming Scottish transportation into zero-emission.

Milev et al (2019) investigated the impact of replacing every vehicle in Scotland by an electrical vehicle. Using their methodology, the estimated subsidy for electrical vehicles would be for 2020. Their results show that the replacement would lead to an approximate 33.7% decrease in the total carbon dioxide emissions. In terms of the financial impact on individuals, they are able to achieve around 69.1% savings each year by switching to the electrical vehicle in the long term based on the cost structure of electrical vehicle consumption – higher initial cost with lower running cost.

Therefore, the investment in EV charging infrastructure and continuous grant in EV consumption are expected to accelerate the pace of cutting carbon emission from transportation. In addition, the demand for faster charging speed and longer driving range would stimulate technology innovations in related areas and provide new job opportunities with increasing entrants into the market.

More Green:

Scottish government has set out a commitment to plant 18,000 hectares of new woodland each year by 2024 and to restore at least 250,000 hectares of peatland by 2030.

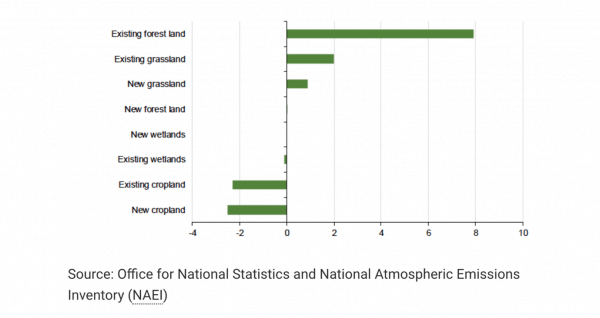

On the one hand, the increased coverage of green space would reduce the exposure of extreme climate to rural areas of Scotland. From Figure 1, we can also see that forest land is the largest source of net sequestration of carbon emissions. Preserving and expanding green space is thus critically effective in achieving net zero emission. Each new hectare of forest and woodland created is estimated to remove seven tonnes of CO2 on average from the atmosphere each year. That is 14.5% of Scotland total CO2 emission in 2019.

Figure 1: Sources of Net Sequestration by Broad Habitat, Scotland, 2017

On the other hand, forestry and woodlands bring economic benefits, business opportunities and technology innovation incentives. The forestry sector expansion would first directly lead to investment and new jobs. Firstly, forestry related recreation and tourism are likely to produce new profit-generating businesses and employment opportunities. It is expected that more than £1 billion in annual economic value would be created, and 25,000 plus jobs would be supported. Meanwhile, the development of forests and woodlands impose a positive externality on people’s lives in urban areas, as green space is vital for people’s physical and mental health especially with the ongoing covid pestering the work and life of everyone. Secondly, the investment and development in the forest and woodland industry would breed technology advancement in supply chain, from forest nurseries through to wood fibre processing companies. For instance, the technology of remote sensing has revolutionised traditional forest management, and real-time information could be used to improve connectivity between the forest and the sawmill.

Agriculture’s future:

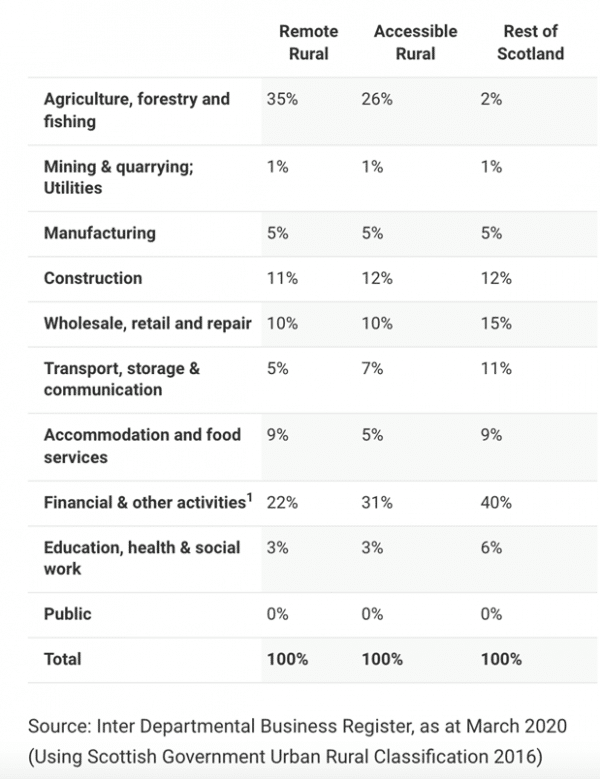

In Scotland, agriculture is the second highest cause of greenhouse gases after transport and is responsible for 23.9% of all emissions. Agriculture makes up 0.8% of Scottish total output in 2019, but it contributes to 30.5 % of the rural economy (Table 2), thus the key job market in rural Scotland. Given its importance in rural economy, here we focus on analysing climate change effect on agriculture in the rural areas and how policies may influence the farmers. We have seen a new round of agri-environmental investment will be delivered as part of an overall £36 million budget, including funding to help deliver the commitment to double the land used for organic funding. With customers’ awareness of the environmental effect caused by raising animals as well as catching fishes, it is critical for those farmers to transform their farming focus and learn new technology and skills. In addition to organic funding, traditional farmers are seeking entrepreneur ways to increase income. The springs of farmers with an average 60 years old returned home with business management knowledge and entrepreneur skillsets acquired from university and work experience, they establish a series of that cater to the new travelling modes of young people and new families.

Table 2: Percentage of Small and Medium Enterprises by industry sector and 3-fold Urban Rural category, 2020

On the macro level, Scotland agriculture faces challenges posed by the Brexit effects and international trade deals UK recently signed with Australia and New Zealand. Firstly, the current agriculture sector is suffering from the labour shortage problems, along with farming employees’ welfare issues, which may lead to production below expected demand. In the fruit and vegetable growers there was a 20% shortage in seasonal workers, while a similar scene is observed in the meat and dairy sector. Without further immigration policies and better welfare policies for those overseas workers, farmers in Scotland would not be able to meet their food and drinks targets, and we would see an increase in produce prices for the following years. In addition, the subsidies and income farmers get might take a hit from a cut in EU’s agriculture funding, from £1.8 billion per year to £0.9 billion per year till 2027. While the Scottish government promises a £65 million investment coming in the coming year, how efficient those money would support the transformation into organic farming are not to be precisely evaluated because farmers may not follow or even look at the piled documents of instructions government sent out to them. Another huge source of pressure comes from imports from in New Zealand and Australia. With UK government signing the trade deals eliminating trade tariffs on certain produce, such as fresh apples, beef and lamb meat and dairy products, the farmers in Scotland would face strong competition from these exporters. Although from the Scottish consumers’ point of view, they have more options to choose and a possibly lower price; for Scottish farmers, and British farmers in general, the fierce competition from mega farms in New Zealand and Australia might squeeze out small farms in the UK. We may see a drop in employment opportunities and household incomes in the rural areas if Scottish farming failed to transform and innovate its business properly and timely, as suggested in the last paragraph.

Conclusion:

Tackling climate change while improving Scottish people’s welfare would be a challenging journey with the unclear future of immigration policies, farming subsidies and trade deals after Brexit. However, as we have seen, Scottish government is actively investing in transformation of key sectors with largest carbon emission. The next step requires continuing investment into net zero transportation methods, more detailed guidance on assisting farming transformation, targeted investment and incentivise programs for small businesses and start-ups.

Reference list:

- Berry K. et al, Update to the Climate Change Plan – Key Sectors. Link: https://digitalpublications.parliament.scot/ResearchBriefings/Report/2021/1/12/109b01e8-6212-11ea-8c12-000d3a23af40

- Goodall S., 15th June 2021, Forestry and wood processing delivering real jobs and growth to rural Scotland, The Scotsman. Link: https://www.scotsman.com/news/opinion/columnists/forestry-and-wood-processing-delivering-real-jobs-and-growth-to-rural-scotland-stuart-goodall-3270314

- Graeme D., 13 September 2021, Answers to “To ask the Scottish Government how much has been spent to date on infrastructure for electric vehicles, and how much it plans to spend in the next five years”. Link: https://www.parliament.scot/chamber-and-committees/written-questions-and-answers/question?ref=S6W-02326

- Henaughen K., 10th Jan 2022, A look back at Scottish farming’s 2021(part four). Link: https://www.thescottishfarmer.co.uk/features/19836809.look-back-scottish-farmings-2021-part-four/

- Illmann U. and Kluge J., Public charging infrastructure and the market diffusion of electric vehicles, Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, Volume 86, 2020, 102413, ISSN 1361-9209. Link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2020.102413.

- Keane K., 7th Jan 2020, Farmers could ‘comfortably’ cut emissions by a third, BBC news. Link: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-51013598

- Milev G., Hastings A. and Al-Habaibeh A., The environmental and financial implications of expanding the use of electric cars – A Case study of Scotland, Energy and Built Environment, Volume 2, Issue 2, 2021, Pages 204-213, ISSN 2666-1233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbenv.2020.07.005.

- Sandford A. and Hanrahan L., 3rd Jan 2022, A year since Brexit: How bad are the UK’s labour shortages now? Link: https://www.euronews.com/2021/12/30/a-year-since-brexit-how-bad-are-the-uk-s-labour-shortages-now

- Schulz F. and Rode J., Public charging infrastructure and electric vehicles in Norway, Energy Policy, Volume 160, 2022, 112660, ISSN 0301-4215. Link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112660.

- Scottish Government, 15th Dec 2021, Supporting Rural Scotland. Link: https://www.gov.scot/news/supporting-rural-scotland-1/

- Scottish Government, 15th Dec 2021, Supporting Rural Scotland. Link: https://www.gov.scot/news/supporting-rural-scotland-1/

- Scottish government, 16 Dec 2020, Update to the Climate Change Plan 2018 – 2032: Securing a Green Recovery Path on a path to net zero. Link: https://www.gov.scot/publications/securing-green-recovery-path-net-zero-update-climate-change-plan-20182032/documents/

- Scottish Government, 27 March 2020, Scottish Natural Capital Accounts: 2020. Link: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-natural-capital-accounts-2020/pages/2/

- Scottish Government, 30th Jun 2020, Farm Business Survey 2018 – 2019: profitability of Scottish farming. Link: https://www.gov.scot/publications/farm-business-survey-2018-19-profitability-scottish-farming/pages/2/

- Scottish Government, Scotland’s Forestry Strategy – 2019 – 2029. Link: https://www.uktreescapes.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/scotlands-forestry-strategy-2019-2029.pdf

- The Economist, 12th Jun 2021, Why farms are moving into solar energy, camp sites and natural burials. Link: https://www-economist-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/britain/2021/06/10/why-farms-are-moving-into-solar-energy-campsites-and-natural-burials

- The Economist, 28th Nov 2020, Can farming be greener after the common agricultural policy? Link: https://www-economist-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/britain/2020/11/28/can-farming-be-greener-after-the-common-agricultural-policy

- Willems M., 11th Jan 2022, British Farmers face bankruptcies as £1.8 bn in EU agriculture cash dries up: MPs warn ‘blind Brexit optimism’ may lead to jump in food prices, CITY A.M. Link: https://www.cityam.com/british-farmers-face-bankruptcies-as-1-8bn-in-eu-agriculture-cash-dries-up-mps-warn-blind-brexit-optimism-may-lead-to-jump-in-food-prices/

Authors

Xiaoxuan Sha

Xiaoxuan is a penultimate-year student studying Economics and Mathematics at University of Edinburgh.

-768x432.jpg)