On Friday, we hosted the second Global Environmental Measurement and Monitoring (GEMM) Network at Strathclyde.

GEMM is a network of scientists, engineers, economists, lawyers and policymakers who are all seeking to better understand how changes in our environment will impact our economy and society.

The initiative was established by Strathclyde in partnership with The Optical Society (OSA) and the University of Stanford’s Stanford Photonics Research Center. The first meeting took place in Stanford in 2018.

The event involved a number of speakers from as far afield as New Zealand and from much closer to home, including Scottish Enterprise and the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency.

One way in which the FAI has become involved in the group is through developing our economic modelling capacity to take the environment into much greater account than in ‘traditional’ economic models.

So far, we’ve been developing our models in a number of ways, including capturing renewable energy, carbon emissions, water usage and natural capital.

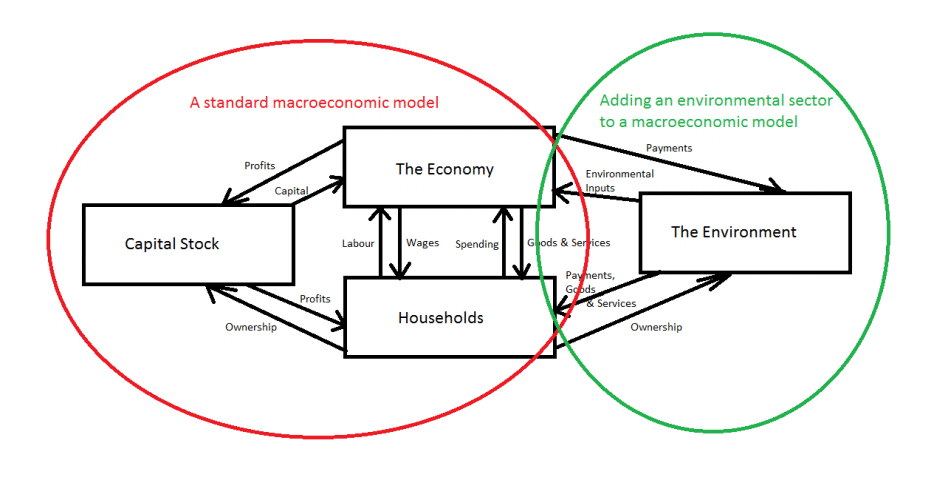

Our macroeconomic models – formally called Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models – consist of a large series of interconnected equations and a database of real data that describe the Scottish economy.

They can be used to model how changes in policy or an economic outcome can affect the rest of the economy – for example, how a change in tastes can affect prices and the quantities of goods produced; or how decisions such as Brexit might impact on jobs, investment and output in the long-run.

Now traditional CGE models are built around two primary inputs that determine the production of goods and services in our economy – physical capital and labour.

To use the example of a farm, labour refers to the value of the tasks undertaken put in by farm workers – planting and harvesting crops, milking animals, maintaining equipment etc., while physical capital refers to the buildings, machines and equipment used such as tractors, barns, fences etc.

But clearly if we are interested in how the environment might be impacted by economic policies, or how changes in the environment might impact upon economic outcomes over time, such an approach is clearly limiting. For instance, two farms with the very same labour and capital could produce different levels of output depending upon their own natural capital – e.g. the quality of the soil, precipitation, flat and unblemished fields, etc.

At the same time, over-farming may weaken the natural capital of a farm meaning that whilst its output might increase in the short-run, in the long-run its output might be severely negatively impacted.

We have been working on including natural capital – and other more detailed environmental accounts – as another input to the production function of our models.

Natural Capital in FAI economic modelling

The natural environment can be envisioned as its own sector of the economy. It provides ecosystem services to other sectors in exchange for payments. These payments are the final profits from users of those services once all other costs and profits are accounted for. Essentially, the leftover profit of a farm is the amount “owed” to the farmland, or the amount the environment would charge for its services if it could.

Now incorporating all of the different elements of natural capital into a macroeconomic model such as this is not straightforward given the wide range of ecosystem services. These are typically grouped as “provisioning” services – things produced by nature but consumed by the economy, such as oil and gas resources, biomass, or water – “regulating” services – such as flood prevention or the sequestration of carbon from the air by vegetation – or “cultural” services, such as the recreational opportunities.

But with careful application and ever improving data it has proven possible.

Our extended model can now be used to see how changes in the natural environment, whether they are short term shocks like a period of drought, or long term structural changes such as climate change or human exploitation, might not only effect the supply of ecosystem services but also create knock-on effects to the economy.

In time, it will be able to capture key elements like recycling of waste and development of waste management services which don’t just benefit the economy but also the environment.

Such an approach has the added benefit of being able to help tackle the ongoing debate around the usefulness of GDP as a measure of long-term economic progress.

Measures like GDP can be misleading as an increase in activity could result from short-sighted overuse or destruction of the environment. In our model, any policies which do that, but lead to a long-term erosion of Scotland’s natural capital, will be shown to have a negative impact on our economy over time.

It’s one of our most interesting and exciting areas of research. If you’re interested in hearing more about our work, please watch-out for upcoming publications.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.