In 2017, the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act set statutory interim targets for child poverty due in 2023/24 and final targets due in 2030/31. The data showing whether or not the 2023/24 targets were met will be released on Thursday.

The targets refer to four measures of poverty: relative poverty, absolute poverty, low income and material deprivation, and persistent poverty. Of these, relative poverty is generally treated as the headline measure. The statutory target for relative poverty is less than 18% by 2023/24 and less than 10% by 2030/31; as of 2022/23, relative child poverty was 26%.

Our latest report models policy packages that could reach the final relative child poverty target of 10% by 2030/31. We explore how the recent announcement that the Scottish Government will mitigate the two-child limit will help with progress towards the targets and what else might be required.

Our modelling shows that meeting the targets is still feasible but will require sizeable additional investment beyond what is currently proposed.

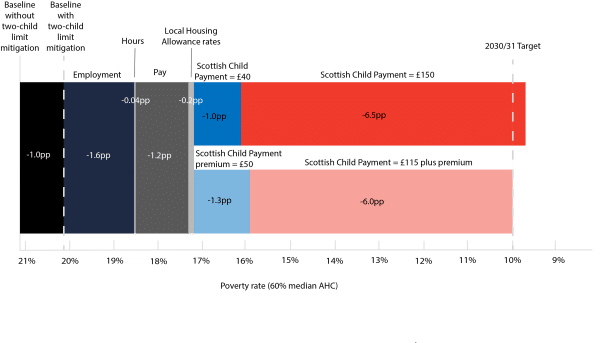

We estimate that, based on policy currently in place and no other policy changes, the gap between current poverty levels and the statutory target for relative poverty is around 11 percentage points.

The recently announced decision to mitigate the two-child limit in Scotland will reduce the gap to 10 percentage points (see chart).

Chart: Policy packages to meet the 2030/31 child poverty targets

Source: FAI calculations using the IPPR tax-benefit model

Notes: All poverty rates are based on a poverty line set at 60% of median income after housing costs.

If the Scottish Government is able to maximize levers to support parents into work and to increase their hours of work and pay, this will reduce child poverty by a further 2.8 percentage points.

Of this, 1.2 percentage points come from improving rates of pay for working parents, while the remainder comes from an increase to parental employment. Increasing hours worked for parents who are already in work makes very little difference, mainly because working parents already have quite high hours.

Given the limited levers available to the Scottish Government, additional social security interventions will likely be required to close the remaining gap of 7.2 percentage points.

These social security interventions could be a combination of changes to better cover housing costs through existing benefits, premia applied to other means tested benefits for certain groups, or an increase in an existing payment such as the Scottish Child Payment (SCP). Other potential levers, like rent controls or an increase in the stock of social housing, are left for further research.

We test a policy that increases support for households who rent from private landlords. Support under Universal Credit and Housing Benefit for rent is defined by the Local Housing Allowance (LHA). We increase LHA so that it can cover up to 100% of rent costs; this could potentially be done by the Scottish Government through discretionary payments or other means of topping up rent support. This policy has a minimal impact on child poverty of around a 0.2 percentage point reduction. The limited impact of the policy is likely due in part to a high proportion of households in poverty in social housing who don’t benefit from the policy.

Of the possible levers within the social security system, we conclude that increases to SCP are the most effective tool available to the Scottish Government.

We test two structures for SCP. The first, shown in the top arm of the chart above, is a flat rate per week, per child – the current structure. The second, in the bottom arm of the chart, is a flat rate per child plus a per-household premium for certain priority households that are less likely to be reached by the employment policies included in this analysis.

In the first structure, we show that the £40 per week, per child in this year’s prices that many organisations have campaigned for would reduce relative child poverty by about 1 percentage point, leaving a 6.2 percentage point gap. To completely close the gap using only a flat rate of SCP, the rate would have to be £150 per week, per child in 2030/31.

Alternatively, under the second structure, a per-household premium of £50 per week for households with a disabled member or a child under one would reduce relative child poverty by 1.3 percentage points. Increasing the flat rate of SCP to £115 per week, per child in 2030/31 on top of the premium would then meet the 2030/31 target of 10% relative poverty. Because it is more targeted, this second structure comes at a lower additional cost (£1.5 rather than £1.8 billion in 2030/31).

The cumulative additional cost of the policies we have modelled is between £4.6 and 4.9 billion in current prices. This is a substantial investment, equivalent to about 75-80% of the budget for devolved benefits in Scotland in 2024/25. About 60% of the total additional cost of the policies comes from an expansion of childcare for ages 1-4 and after-school care for ages 5-10 associated with the employment policies we have modelled.

The options we have modelled are of course not the only path to meeting the targets, and there are potentially many other options that could cumulatively make a big difference – for instance, a Minimum Income Guarantee, additional rent and housing policies, or further measures to increase benefit take-up. However, the timeframe for interventions to take effect is relatively short, which limits the range of options now available to the Scottish Government if they are to meet the targets.

The final Scottish Government child poverty delivery plan is due before the end of March 2026. Within this, the Scottish Government will have to set out the measures that they will take in the period up to 2030/31 and the contribution they will make to meeting the targets. This final delivery plan will come a few months before the Scottish election. Given the cross-party support for the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act it will be critical that all parties are able to say how they will meet the targets. We look forward to both the delivery plan and the party manifestos, and would urge the Scottish Government and the individual parties to do their own modelling of proposed measures to credibly demonstrate how the targets will be reached.

Read the full report here.

abrdn Financial Fairness Trust has supported this project as part of its mission to contribute towards strategic change which improves financial well-being in the UK. The Trust funds research, policy work and campaigning activities to tackle financial problems and improve living standards for people on low-to-middle incomes in the UK. It is an independent charitable foundation registered in Scotland (SC040877).

Authors

Hannah is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. She specialises in applied social policy analysis with a focus on social security, poverty and inequality, labour supply, and immigration.

Chirsty is a Knowledge Exchange Associate at the Fraser of Allander Institute where she primarily works on projects related to employment and inequality.

Emma Congreve is Principal Knowledge Exchange Fellow and Deputy Director at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Emma's work at the Institute is focussed on policy analysis, covering a wide range of areas of social and economic policy. Emma is an experienced economist and has previously held roles as a senior economist at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and as an economic adviser within the Scottish Government.