Over the last few months, we’ve been working on getting a better picture of employment initiatives that impact people with learning disabilities, learning difficulties and developmental disorders in Scotland. This work is the first part of our third programme of research funded by Acorns to Trees.

This blog summarises our progress on mapping the employability landscape and key issues we’ve uncovered to date. We are continually learning more on this topic and aim to provide updates throughout the next year. We welcome feedback from those who work in this area – please get in touch if you would like to share your own experience.

A quick reminder: we have expanded our learning disabilities programme to include learning difficulties and developmental disorders, and we will refer to these groups of conditions throughout.

What employment initiatives are available for people with learning disabilities, learning difficulties and developmental disorders?

Postcode lottery by local authority

Most employability interventions in Scotland are provided at a local authority level. This is due to the No One Left Behind funding system and strategy, which provides funding to all local authorities while allowing each local authority the freedom to choose the services they provide. While there are standards each local authority must uphold in terms of service quality, the type of service available varies.

All local authorities are now required to provide Specialist Employability Services – this refers to employability services for those with disabilities and health conditions. However, as mentioned above, what this looks like is at the discretion of the local authority.

Our review of the services provided by local authorities has highlighted that many of the programmes/interventions available are not specifically for disabled people or people with health conditions. Instead, various organisations with an understanding of the needs of disabled people are included in Local Employability Partnerships or service provision, and individuals are assigned to an organisation that best fits their needs and experience. What this means in practice is that Specialist Employability Services will be provided by one or more organisations in each local authority, and these organisations tend to receive funding through No One Left Behind.

How does it actually work?

Rather than apply to a specific service, the general approach across Scotland is for individuals to contact the employability provider for their local authority (or be referred to this provider), where they are assigned a key worker and assessed so that they can be placed with the most appropriate service/programme available.

Many of those with learning disabilities, learning difficulties or developmental disorders will receive what is referred to as Specialist Employability Services (SES) with Key Working. This means they are assigned a key worker and the key worker helps them to reach a positive outcome – this could be employment, but it could also be something that helps them towards employment such as education, volunteering or even something like driving lessons if they live in a rural area.

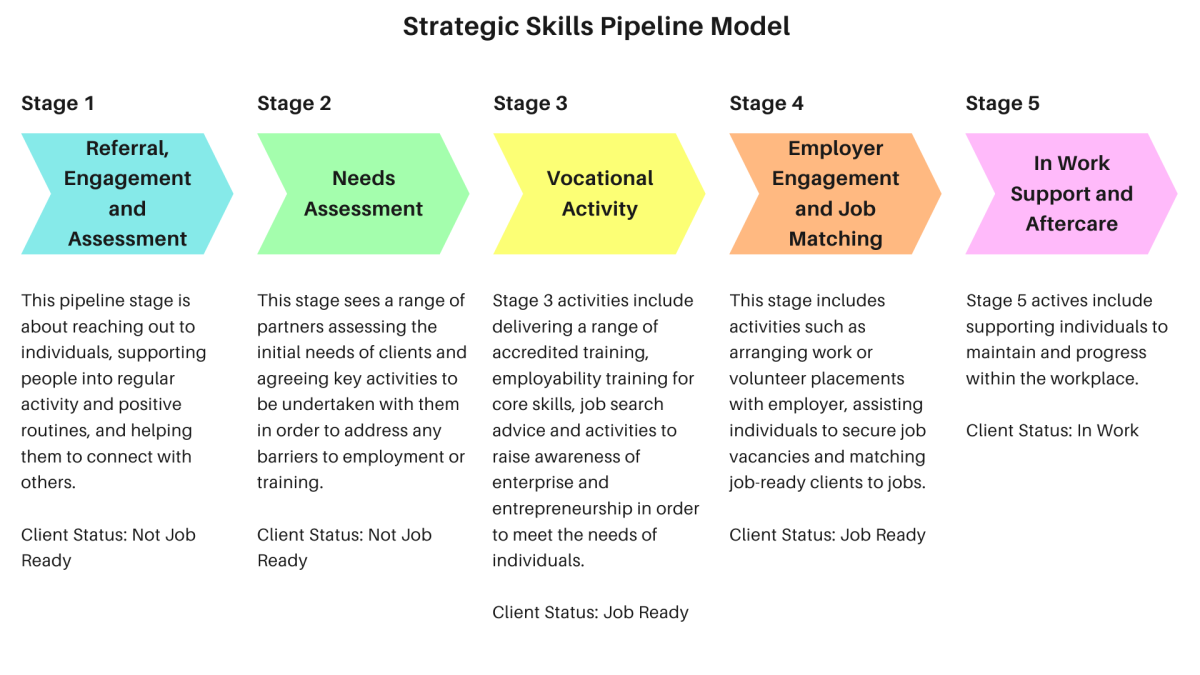

Those who use employability services are thought of as belonging to one of five stages of the employment pipeline (see graphic below). Stage 1 is the furthest from the labour market, while Stage 5 refers to those who are in work.

Source for graphic: Employability in Scotland 2025 (graphic created by FAI)

Most local authorities also provide or fund at least one employability programme which is more specific in nature. The main specialised interventions provided/commissioned by local authorities include:

- The 5-Stage Supported Employment model

- Individual Placement and Support (IPS)

- DFN Project SEARCH

- Vocational Rehabilitation/Condition Management

DFN Project SEARCH is the only intervention regularly provided/commissioned by local authorities which is specific to people with learning disabilities and autism. Supported employment may be available to a broad range of jobseekers, or to a specific group (Glasgow City Council, for example, only provide Supported Employment to individuals with learning disabilities and autism).

IPS is more targeted towards those with severe mental health conditions, and Vocational Rehabilitation/Condition Management is focused on maintaining work or returning to work for those with disabilities/health conditions who have already been employed.

Again, each of these interventions are only provided by some local authorities.

What else is out there?

Apart from local authority provision, many third sector organisations provide employment interventions, sometimes in partnership with public bodies.

For people with learning disabilities, learning difficulties and developmental disorders, one key programme in Scotland is Breaking Barriers. Breaking Barriers is a partnership between Enable, universities and businesses which allows young people to receive an accredited qualification from a university and gain work experience with a large employer.

Third sector organisations also provide employer-focused initiatives in Scotland. Inclusion Scotland, for example, provides ‘employerability’ training for employers to improve their understanding of, and confidence in supporting, disabilities and health conditions at work. Apt, a recent Public-Social Partnership (PSP) led by the Scottish Union of Supported Employment (SUSE) designed to target the disability employment gap, brought together over 40 partners from the public and third sectors to provide training and other interventions to employers.

Employer interventions can also be targeted to specific types of disabilities or health conditions. In England, WorkFit is a tailored service dedicated to training employers about the learning profile of people who have Down’s syndrome so that they can be supported in the workplace. Down’s Syndrome Association also help potential employees prepare for work and match them with employers on the WorkFit programme.

Down’s Syndrome Scotland (DSS) are currently working on their own inclusive employment programme for employers in Scotland. For DSS, inclusive employment is about creating the right workplace environment for jobseekers with Down’s Syndrome. To do this, the programme aims to support employers to remove biases and barriers in the workplace by providing training to increase awareness and confidence, and highlighting the benefits of diversity and inclusion.

Third sector organisations sometimes have the flexibility to be more innovative in their approach to employment interventions. However, they can also lack the resources to evaluate their work effectively. More on evaluation later.

How are available employment initiatives funded?

The employability funding landscape has changed significantly over the last ten years. The table below shows the average proportion of various funding sources used by 108 stakeholders, including local authorities, third sector organisations and other national organisations who provide local employability services (Farooqi 2025). Within Farooqi’s sample, there was large variation in stakeholders’ reliance on different types of funding – some stakeholders had highly diversified funding, while others were entirely reliant on a single funding source.

| Funding Source | Average proportion (%) |

| Local Authority core budget | 21.84 |

| Additional Scottish Government funding streams (including No One Left Behind) | 24.94 |

| UK Government funding streams (e.g. Shared Prosperity Fund) | 11.89 |

| Other sources (e.g. private/philanthropic) | 8.13 |

Source for table: Farooqi 2025

While the Scottish Government’s main employability funding stream is No One Left Behind (NOLB), NOLB and other Scottish Government programmes together account for only around a quarter of total funding across participants.

NOLB funding is competitive and is provided in one-year cycles. Farooqi’s report highlights that funding delays are common and significantly impact delivery of employability support. As part of our review, we further heard from stakeholders that the competitive nature of NOLB funding was sometimes disincentivising wider sharing of detailed data on numbers of service providers and outcomes – bear this in mind for the next section.

How successful are current employment initiatives in Scotland?

Measuring the success of an employment initiative is reliant on two things: good data, and a clear understanding of how data can be used to establish causality.

What data is available on employment initiatives?

The Scottish Government publishes NOLB statistics on a quarterly basis. The latest NOLB data was published on 22nd October 2025. These statistics provide a breakdown of the number of people receiving employability services in Scotland by long term health condition or disability, and the number of people achieving positive outcomes by this same category.

The good news is we have a learning disability category in NOLB data, as well as categories for learning difficulties and autism spectrum condition.

To date, 16,177 people with a learning disability, learning difficulty or autism have received employability support through NOLB since its inception in April 2019 (though this figure may double count individuals who have reported more than one condition). This includes 4,110 people with a learning disability, 6,570 with a learning difficulty, and 5,497 autistic people. To give an idea of scale, a total of 92,523 people have received employability support through NOLB. This means roughly 17% of all recipients of employability support through NOLB reported a learning disability, learning difficulty or autism (again, this may double count those with multiple conditions – the individual stats for each condition are 4%, 7% and 6% of total recipients respectively).

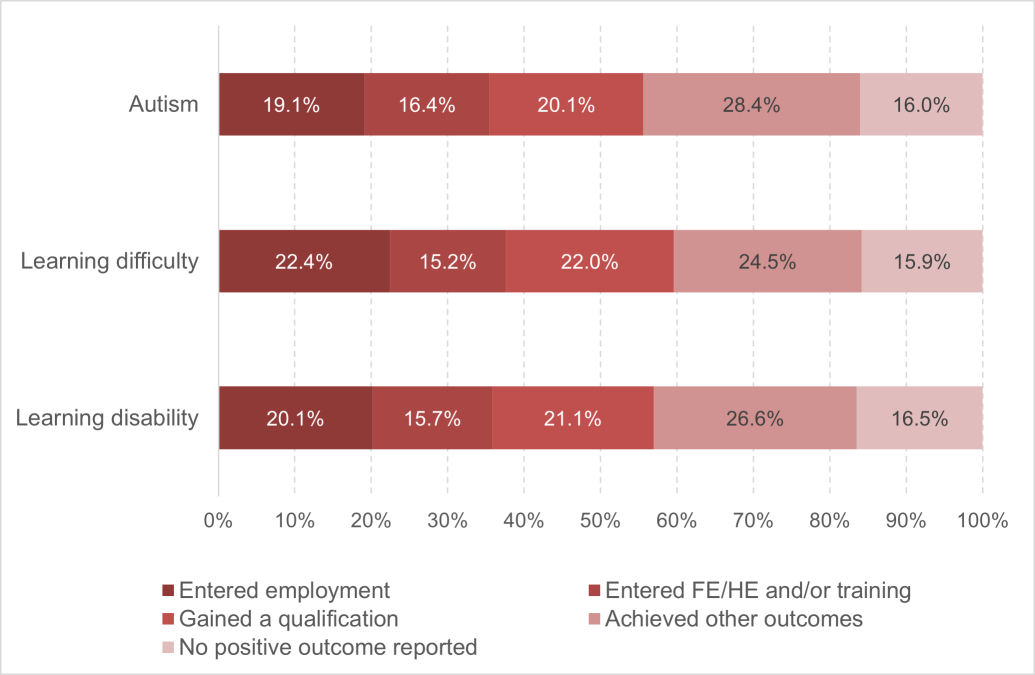

The chart below shows what percentage of each of these groups has achieved various outcomes recorded in the statistics, including employment, qualifications and more. For comparison, of all the people supported under the NOLB approach, 31% have entered employment. The percentage of those who are disabled who have entered employment to date is 22%. We report both of these figures because people who are disabled are more likely to be further from the labour market.

Chart 1: Outcomes breakdown for employability recipients with certain long-term health conditions/disabilities

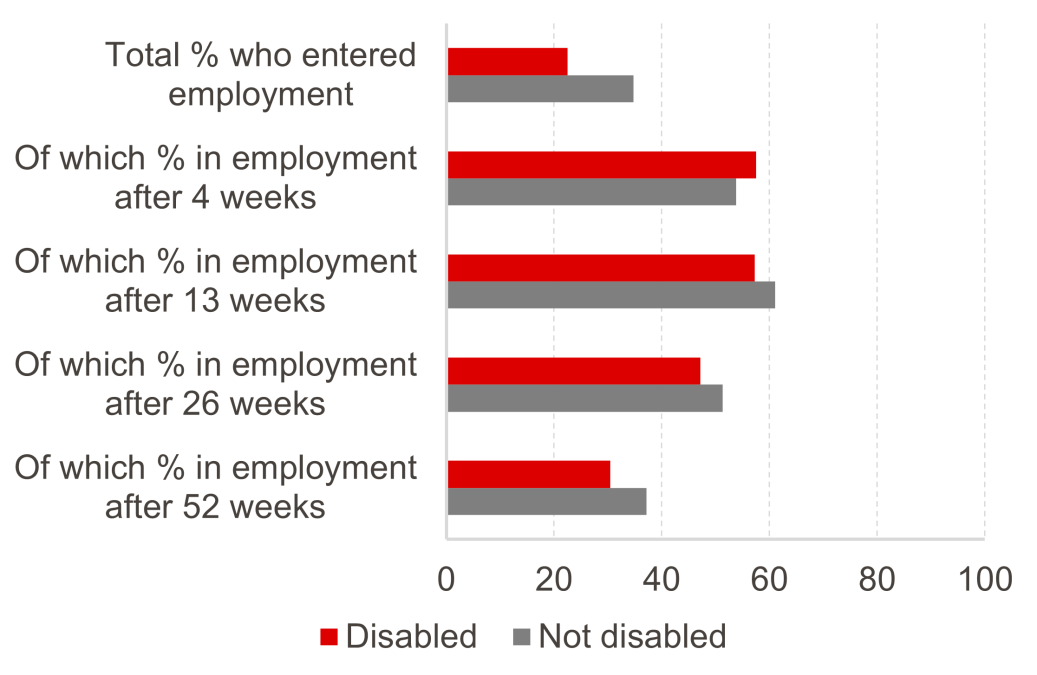

However, getting a job is not the same as keeping a job. When it comes to longer term outcomes, we only have information at the disabled/not disabled level, and not yet at the level of long term health condition (LTHC). The below chart shows that when it comes to retaining employment over time, disabled recipients start to fall behind non-disabled recipients at 13 weeks, and this gap widens at both 26 and 52 weeks. These statistics also don’t show continuous employment – an individual could have lost a job and gained another, and still be counted within the percentage ‘in employment after X weeks’.

Chart 2: Employment rates over time for employability recipients who secured a job, by disability status

Source for chart: Scottish Government. Note: there is a significant percentage of employability recipients whose disability status is unknown – they are omitted from this chart. Percentages are also affected by whether employability providers are able to reach service users over time.

On top of the lack of long-term outcomes data by LTHC, there is still a lot we don’t know based on the available statistics. How easy or difficult was it to achieve the outcomes reported for these groups? Are those who enter employment getting good-quality jobs? What about levels of underemployment and skills utilisation? What impact is employment having on individuals’ health and well-being?

There are further administrative data held by local authorities and other providers which could potentially answer some of these questions, but most only publish what is required by the Scottish Government through NOLB reporting. We believe this is at least partly due to the competitive nature of funding and the risk of being undercut by competing providers. Lack of resource or analysis capacity may also contribute to more detailed data being underutilised at the local authority level.

What about causality?

Even in the presence of detailed outcomes data, we often still can’t say definitively whether an employment initiative has been successful. Outcomes data tells us that in year X, a person was unemployed, and in year Y, they got a job. But it doesn’t tell us what caused them to get a job. To prove causality, we need to understand what would have happened to that individual if they hadn’t taken part in the employment initiative.

In economics and policy evaluation, this is called a counterfactual. It’s a hypothetical scenario that estimates what would have happened had a policy/intervention not occurred.

We obviously can’t track an individual doing two different things at once. Instead, we can use techniques like randomising who a policy/intervention affects (like medical trials), or following a similar population who aren’t affected by the policy/intervention. (We’ve got a more detailed report on evaluation as part of another FAI project coming soon, so stay tuned for that).

A good evaluation of an employment initiative should include something that indicates causality. But this involves collecting data for a counterfactual from the beginning of the initiative (or even before it starts) and often requires analytical skills that might not be held by those providing the employment initiative. While we did find some independent evaluations of employment initiatives, many of these were commissioned retroactively which meant the data required to show causality wasn’t available.

In short, at this stage – we’re not sure how effective any of the employment initiatives provided in Scotland are for people with learning disabilities, learning difficulties and developmental disorders.

So, what causal evidence is available?

Internationally, specific models of supported employment such as Individual Placement and Support have been shown through randomised controlled trials to have a causal impact on disabled people’s employment (see e.g. Frederick and VanderWeele 2019). But for our population of interest specifically, less evidence is available.

We found some systematic reviews and literature reviews of studies around employment outcomes for people with learning disabilities, learning difficulties and developmental disorders specifically (Encott and Dew 2025; Avellone et al 2023; Fong et al 2021; Almalky 2020; Qian et al 2018). The reviews highlight studies of varying quality, and they call for further research in this area.

We particularly noticed a lack of causal evidence around employability interventions mentioned in the reviews. We undertook a mini, targeted systematic review looking for papers that tested the causal impact of employment interventions for people with learning disabilities, learning difficulties and developmental disorders, and found only five studies that matched our criteria across three academic databases.

For those who are particularly interested in causal studies, there are some details and links in the table below for further information.

| Author, Year | Summary |

| Inge et al 2024 | Found in a randomised controlled trial with 46 individuals aged 18-24 with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) that those who experienced customised employment were significantly more likely to secure competitive integrated employment (CIE). |

| Iwanaga et al 2022 | Did a non-experimental causal study of over 4,000 youths, results demonstrated that transition-age youth and young adults with intellectual disabilities who received supported employment were more likely to achieve CIE outcomes, earn higher wages, and work longer hours weekly than the control group. |

| Seward 2022 | A PhD thesis which used propensity score matching and found that supported employment had a significant effect on employment outcomes for transition age youth with IDD from low-income backgrounds (around 30,000 sample size, secondary data from US). |

| Wehman et al 2017 | Did a randomised controlled trial (RCT) with 49 18-21 year olds, treatment group took part in project SEARCH and received autism spectrum disorder (ASD) supports, control group attended ‘high school as usual’. We’re not too sure about the comparability of these groups but results were 90% employment for treatment group vs 6-12% for control group. |

| Cadet 2025 | PhD thesis including a quasi-experimental one-group pretest-posttest design (participants are measured before and after the intervention, no control group) with structured training for employers, significant increase in employers’ confidence and attitudes towards hiring autistic individuals. |

Key conclusions

Here are our conclusions after completing this review.

1. There is a clear need for more employer-focused initiatives

We’ve highlighted in previous research that employers tend to lack confidence hiring people with learning disabilities. However, the focus on employment initiatives is much more often on making individuals more employable, with few initiatives improving the environment for individuals by supporting employers. Furthermore, initiatives that do support employers such as DFN Project SEARCH seem to be more likely to achieve good employment outcomes for individuals with learning disabilities, learning difficulties and developmental disorders. The good news is we’re seeing more of these popping up already in the disability space, with SUSE continuing their Apt work, and Down’s Syndrome Scotland developing an Inclusive Employment programme.

2. NOLB provides some data, but not enough

NOLB summary statistics thankfully have outcomes data by long term health condition/disability, but this only shows whether employment is achieved and not whether it is sustained. There is also no regularly published data on the quality of jobs or wider ripple effects of employment, such as impacts on health and wellbeing. Further published quantitative and qualitative data is likely required to understand how well NOLB is working. However, we heard that the competitive nature of NOLB funding may be disincentivising wider data sharing.

3. Proving that an intervention works is tricky

Even with lots of detailed data, proving that an intervention directly caused someone to become employed is hard. Ideally, we need to follow a control group who don’t receive employability support to prove causality. Evaluations need to be baked in from the start of interventions for best results – something which is uncommon in the current landscape.

4. Causal evidence is sparse internationally too

Proving initiatives work is not a problem unique to Scotland. Even internationally, minimal causal evidence is available for what interventions help people with learning disabilities, learning difficulties and developmental disorders achieve employment.

This blog has been our attempt to summarise a very broad topic. There is a lot of great work going on around trying to show causality and value for money in the employability space in Scotland. Something we haven’t covered in this blog is job crafting – for more on this, check out the new Wishes project funded by NIHR and led by Professor Adam Whitworth at the University of Strathclyde.

Next up, we will be working with stakeholders to look at social security and employment for people with learning disabilities, learning difficulties and autism. Our employment work will continue with further research and resource creation with a range of stakeholders. We are also grateful to be involved in Down’s Syndrome Scotland’s inclusive employment pilot scheme from an early stage, where we hope to assist in a strong evaluation of the programme.

Authors

Chirsty is a Knowledge Exchange Associate at the Fraser of Allander Institute where she primarily works on projects related to employment and inequality.

David is a Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he worked in a range of analytical positions across the public sector, primarily as a statistician.