The estimates of Scotland’s net fiscal balance are out for 2024-25. As we previewed on Friday, there was deterioration of the fiscal balance, which is unsurprising given that the UK’s fiscal balance worsened during that year as well.

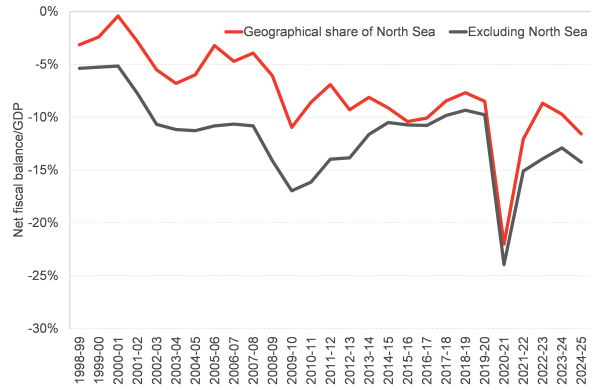

Scotland’s estimated net fiscal balance was estimated to have been -£26 billion, or -12% of GDP, when including a geographical share of North Sea revenues and economic activity.

Chart 1: Scotland’s net fiscal balance as a share of GDP

Source: Scottish Government

The worsening of the fiscal balance in 2024-25 is larger for the figure including the North Sea, in large part because oil and gas tax receipts have fallen – by £0.8 billion, or 0.4% of Scotland’s GDP.

Higher devolved expenditure is the main driver of the widening deficit

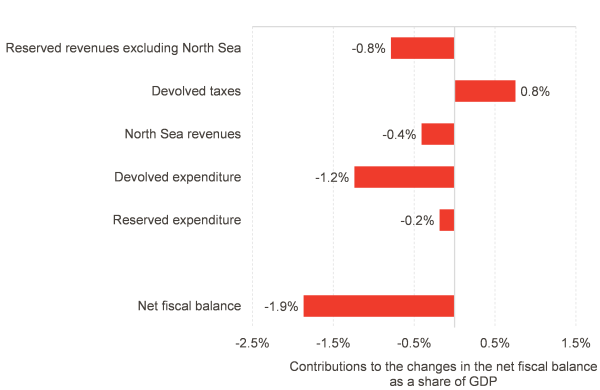

Scotland’s net fiscal balance is 1.9% of GDP worse in 2024-25 than it was in 2023-24, but it is worth looking at what is driving this. We have already seen that North Sea revenues have added 0.4% of GDP to the deficit; reserved expenditure also adds 0.2% of GDP to that figure.

Reserved revenues (excluding North Sea) fell by 0.8% of GDP relative to the previous year, largely as a result of the cut to employee National Insurance Contributions announced in March 2024. Devolved tax revenues near-enough offset this, with Scottish Income Tax accounting for the lion’s share of this increase, although Land and Buildings Transaction Tax revenues also rose by nearly 20%.

But it was the spending side that accounted for most of the deterioration in the fiscal balance. UK Government spending rose by 0.2% of GDP, but it was the 1.2% of GDP increase in devolved expenditure that accounted for most of the 1.9% that the net fiscal balance fell by.

Chart 2: Decomposition of changes to Scotland’s net fiscal balance as a share of GDP in 2024-25 relative to 2023-24

Source: Scottish Government, FAI calculations

This is in many ways unsurprising, as higher spending as a share of the economy has long been the driver of Scotland’s higher net fiscal deficit than the UK’s. Public spending in and for the benefit of Scotland has now risen to 55.4% of GDP, compared with 44.4% for the UK as a whole.

The Scottish Government’s response

The Scottish Government have chosen to welcome the fact that devolved revenues are growing faster than devolved spending. The ministerial statements that accompany statistics often are looking for the positive story from the statistics, and the make any political points.

But let’s take a step back. The consequences of this could be to imply that the Scottish Government are running some kind of surplus on devolved budgets, but of course it does not work like that, for two reasons:

- Devolved revenues are not the main source of funding for devolved spending, which remains the Block Grant; and

- The Scottish Budget may not benefit from all the growth in devolved revenues, due to the operation of the fiscal framework (because, in short, revenues per person have grown more slowly than the rest of the UK if we exclude policy differences).

So this as a message is a little muddled in terms of what it really tells us about the fiscal health of Scotland. And how do we square this with chart 2, which shows that devolved spending was the main driver of the notional deficit?

It’s a question of the relative size of the two numbers. Devolved revenues were around £26 billion in 2024-25, £2.3 billion (9.7%) higher than in the previous year. But devolved expenditure is much higher, at £72 billion. It grew by 6.8% – which while lower in percentage terms, means an increase of £4.6 billion, far outstripping devolved revenue growth.

Another line was brought out in the Scottish Government’s response today:

The 2024-25 Government Expenditure & Revenue Scotland statistics show Scotland’s £91.4 billion revenue was enough to cover all day-to-day devolved spending and all reserved social security, including the State Pension, which amounts to £84.9 billion.

This is an evolution from the line published alongside GERS in 2022:

“But even without North Sea receipts, the record revenue generated was sufficient to cover all day-to-day devolved spending as well as all social security spending in Scotland, including the state pension.

Here’s what we said about it at the time. This time, all revenues are included in the statement (including North Sea).

It is true that total revenues of £94.1 billion are more than devolved current spending of £62.6 billion plus social protection spending by the UK Government of £22.3 billion (£62.6 billion + £22.3 billion = £85 billion).

What this does not include is any capital investment, of course, including £9.4 billion of devolved capital expenditure.

More significantly, there are a number of reserved functions that are also funded outwith these 2 categories – including reserved economic development spending of £1.2 billion (on programmes like Innovate UK), public sector debt interest payments (£8.5 billion), reserved transport spending (£1.2 billion), public and common services (£1 billion, including running administrative services such as HMRC), defence (£5.1 billion) and international services (£0.8 billion, including foreign aid).

Essentially what this statement says is that revenues raised in Scotland cover some, but not all of spending for the benefit of Scotland. Which is what the notional deficit represents.

The Scottish Government also pointed out that GERS allocates defence spending – which is reserved for the UK Government – to Scotland on a population basis, which means apportioning around £5 billion to Scotland, but that ”only £2.1 billion was actually spent with industry in Scotland in 2023-24.”

This appears to be sourced from the Ministry of Defence’s Regional Expenditure With Industry statistical release. However, a quick look at that release shows that it only includes purchases from UK-based companies, omitting purchases from abroad for the benefit of the UK’s military, research and development carried out in house and – crucially – the costs of any MoD staff based in Scotland, civilian or military.

Those statistics show a total of £29 billion of spending, rather the c.£55 billion of defence spending at UK level that occurred in that year. For example, it misses out £15 billion spent on personnel. And Scotland’s share of procurement is actually similar to its population share.

Authors

João is Deputy Director and Senior Knowledge Exchange Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, he was a Senior Fiscal Analyst at the Office for Budget Responsibility, where he led on analysis of long-term sustainability of the UK's public finances and on the effect of economic developments and fiscal policy on the UK's medium-term outlook.

Mairi is the Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, she was the Deputy Chief Executive of the Scottish Fiscal Commission and the Head of National Accounts at the Scottish Government and has over a decade of experience working in different areas of statistics and analysis.