This morning sees the publication of Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (GERS) 2021-22.

These statistics set out three main things:

- The revenues raised from Scotland, from both devolved and reserved taxation;

- Public expenditure for and on behalf of Scotland, again for both devolved and reserved expenditure;

- The difference between these two figures, which is called in the publication the “net fiscal balance” – but as you may well hear colloquially referred to as the “deficit”.

These statistics form the backdrop to a key battleground in the constitutional debate, particularly when it is focussed on the fiscal sustainability of an independent Scotland and what different choices Scotland could make in terms of taxation and spending.

So what do the latest statistics show?

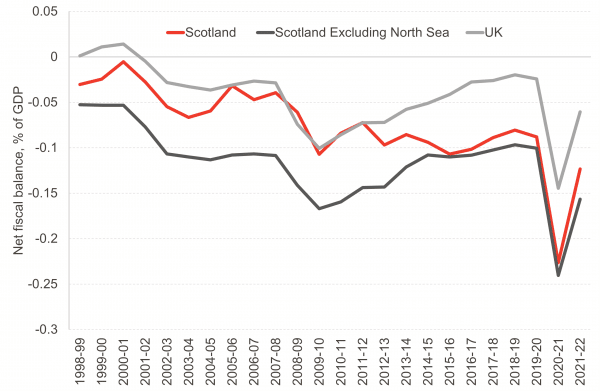

The latest figures show that the net fiscal balance for 2021-22 was -£23.7 bn, which represents -12.3% of GDP. This is a huge fall from the 2020-21 figure of -22.7% of GDP, but we have to remember that this was the first year of COVID-related spending which hugely inflated both the UK and Scottish deficit.

The comparable UK figure for 2021-22 is -6.1% of GDP.

Chart 1: Scottish and UK net fiscal balance, 1998-99 to 2021-22

Source: Scottish Government

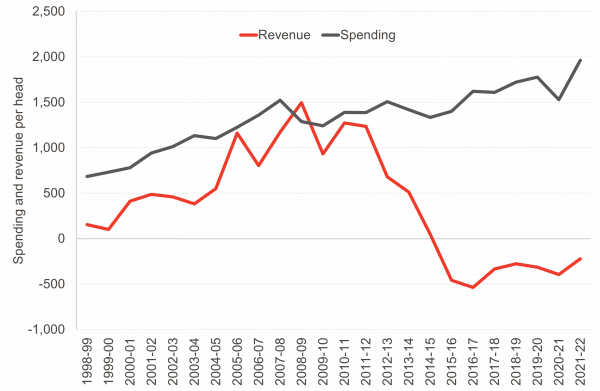

The difference between the Scottish and UK deficit is driven by both sides of the net fiscal balance equation.

Chart 2: Spending and revenue per head, Scotland-UK, 1998-99 to 2021-22

Source: Scottish Government

On revenues, Scotland raised £221 less per head than the UK, whilst on expenditure, Scotland spent £1,963 more per head than the UK average.

One of the changes from the last few years has been the increased contribution from oil revenues, which were estimated to be £3.5bn for 2021-22. [As an aside, there is no revenue from the UK Government’s new “windfall tax” in these figures – that started to be collected in May 2022 so will feature in next year’s GERS].

A BRIEF ASIDE

Work with us

We regularly work with governments, businesses and the third sector, providing commissioned research and economic advisory services.

Find out more about our economic consulting for UK firms and the public sector.

So what do these statistics really tell us?

These statistics reflect the situation of Scotland as part of the current constitutional situation, that is, Scotland as a devolved government as part of the UK. The majority of spending that is carried out to deliver services for the people of Scotland are provided by devolved government (either Scottish Government or Local Government). To a certain extent therefore, the higher per head spending levels are driven by the way that the funding for devolved services is calculated through the Barnett formula. Add on top of that the higher than population share of reserved social security expenditure, and we have identified the two main reasons for higher public expenditure in Scotland.

Let’s go over some of the main points that may come up today when folks are analysing these statistics.

Scotland isn’t unusual in the UK in running a negative net fiscal balance

This is absolutely right. ONS produce figures for all regions and nations of the UK, and these have shown consistently (in normal years, so excluding COVID times) that outside of London and surrounding areas, most parts of the UK are estimated to raise less revenue than is spent on their behalf.

Last year, we discussed the differences between parts of the UK in an episode of BBC Radio 4’s More or Less programme.

The Scottish Government doesn’t have a deficit as it has to run a balanced budget

Again, this statement is broadly true*. The Scottish Government’s Budget is funded through the Barnett determined Block Grant, with some adjustments to reflect the devolution of taxes and social security responsibilities (most significantly, income tax).

Limited borrowing powers are available to the Scottish Government to fund capital investment and cover forecast error, but they do not have the flexibility to borrow for discretionary resource spending.

However, to focus on this around the publication of GERS somewhat misses the point of the publication. It looks at money spent on services for the benefit of Scotland, whoever spends it, and compares that to taxes raised, whoever collects them. As touched on above, the Barnett-determined block grant funds services at a higher level per head in Scotland than in England in aggregate.

*changed from “absolutely” originally given the limited borrowing powers available

Onshore revenues cover devolved spending and social security

This has come up a few time in recent months, and also features in the Scottish Government’s press release:

“But even without North Sea receipts, the record revenue generated was sufficient to cover all day-to-day devolved spending as well as all social security spending in Scotland, including the state pension.

It is true that onshore revenues of £70.3bn are more than devolved current spending of £53.5bn plus social protection spending by the UKG of £16.7bn (£53.5bn+£16.7bn=£70.2bn).

What this does not include is any capital investment, of course, including £8bn of devolved capital expenditure.

More significantly, there are a number of reserved functions that are also funded outwith these 2 categories – including reserved economic development spending of £2.2bn (so on programmes like Innovate UK), public sector debt interest payments (£4.5bn), reserved transport spending (£988m), public and common services (£1.4bn – including running administrative services such as HMRC), defence (£3.9bn), International services (£659m – including foreign aid) etc.

What does this tell us about independence?

Setting aside the noise that will no doubt accompany GERS today, there are essentially two key issues, that need to be considered together.

GERS takes the current constitutional settlement as given. If the very purpose of independence is to take different choices about the type of economy and society that we live in, then it is possible that these a set of accounts based upon the world today could look different, over the long term, in an independent Scotland.

That said, GERS does provide an accurate picture of where Scotland is in 2022. In doing so it sets the starting point for a discussion about the immediate choices, opportunities and challenges that need to be addressed by those advocating new fiscal arrangements. And here the challenge is stark, with a likely deficit far in excess of the UK as a whole, other comparable countries or that which is deemed to be sustainable in the long-term. It is not enough to say ‘everything will be fine’ or ‘look at this country, they can run a sensible fiscal balance so why can’t Scotland?’. Concrete proposals and ideas are needed.

And please guys… dodge the myths!

We have produced a detailed guide to GERS which goes through the background of the publication and all of the main issues around its production, including some of the odd theories that emerge around it. A couple of years ago, we also produced a podcast which you can enjoy at your leisure.

In summary though, to go through the main claims usually made about GERS:

- GERS is an accredited National Statistics produced by statisticians in the Scottish Government (so is not produced by the UK Government) and is a serious attempt to understand the key fiscal facts under the current constitutional arrangement

- Some people look to discredit the veracity of GERS because it relies – in part – on estimation. Estimation is a part of all economic statistics and is not a reason to dismiss the figures as “made up”.

- Will the numbers change if you make different reasonable assumptions about the bits of GERS that are estimated? In short, not to any great extent.

- If you have any more questions about how revenues and spending are compiled in GERS, the SG publish a very helpful FAQs page, including dealing with issues around company headquarters and the whisky industry.

Look out for more analysis

It’ll be interesting to see the coverage of these statistics today and the talking points that are generated given where we are in the constitutional debate.

If you have any questions about GERS for us, then why not get in touch? Submit them to fraser@strath.ac.uk and we’ll try to cover them in a podcast tomorrow!!

Authors

Mairi is the Director of the Fraser of Allander Institute. Previously, she was the Deputy Chief Executive of the Scottish Fiscal Commission and the Head of National Accounts at the Scottish Government and has over a decade of experience working in different areas of statistics and analysis.

Calum is an Associate Economist at the Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) and a Researcher at the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP). He specialises in economic modelling and trade, and holds an MSc in Economics from the University of Edinburgh.

Adam is an Economist Fellow at the FAI who works closely with FAI partners and specialises in business analysis. Adam's research typically involves an assessment of business strategies and policies on economic, societal and environmental impacts. Adam also leads the FAI's quarterly Scottish Business Monitor.

Find out more about Adam.

James is a Fellow at the Fraser of Allander Institute. He specialises in economic policy, modelling, trade and climate change. His work includes the production of economic statistics to improve our understanding of the economy, economic modelling and analysis to enhance the use of these statistics for policymaking, data visualisation to communicate results impactfully, and economic policy to understand how data can be used to drive decisions in Government.