Tackling regional economic disparities has been a priority of successive governments in both the UK and Scotland.

The UK Government’s Industrial Strategy is their latest attempt, with regional growth 1 of 5 ‘foundations of success’. Here in Scotland, ‘cohesion’ – or its new term ‘regional inclusive growth’ – has been a feature of the Scottish Government’s Economic Strategy since 2007.

It is hard to disagree that a country will be economically stronger if every region has the opportunity to fulfil its potential.

However, Scottish and UK policy history is littered with well-intentioned – but ultimately ill-fated – attempts to narrow the gap in economic performance between regions. Many of the challenges are deep-rooted and structural, whilst attempts to tackle them throw-up challenging trade-offs and political risks.

Regional inequalities in Scotland and the UK

Much has been written about the unbalanced nature of the UK economy.

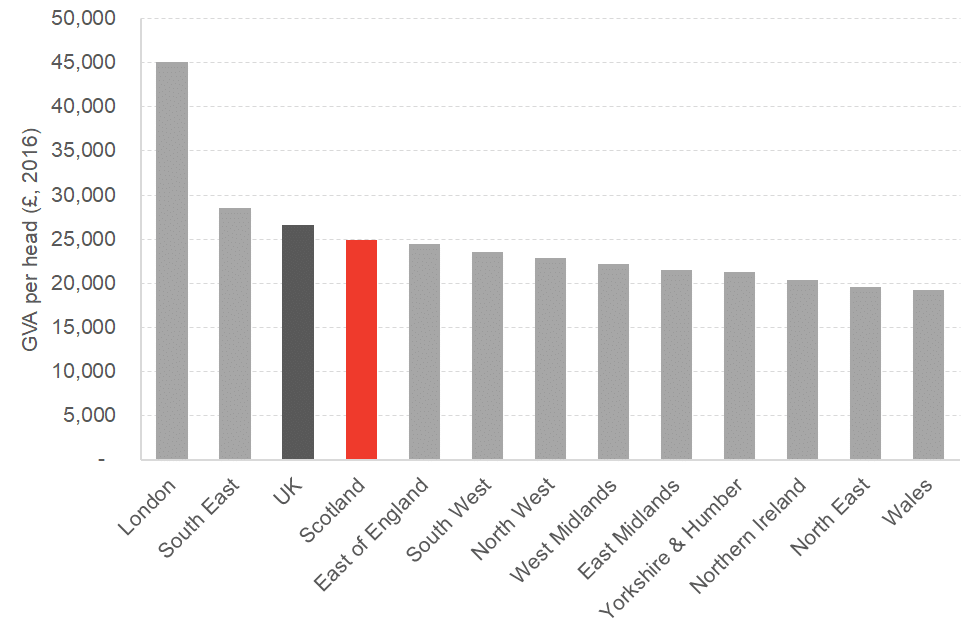

Scotland performs relatively well despite that context. Our onshore GDP per head was just below £25k in 2016 – 3rd behind London and the South East.

Chart 49: GVA per head across the UK (2016)

What is stark is the variation in economic performance by UK region. GVA per head in London is over 70% higher than the UK average. (Chart 49)

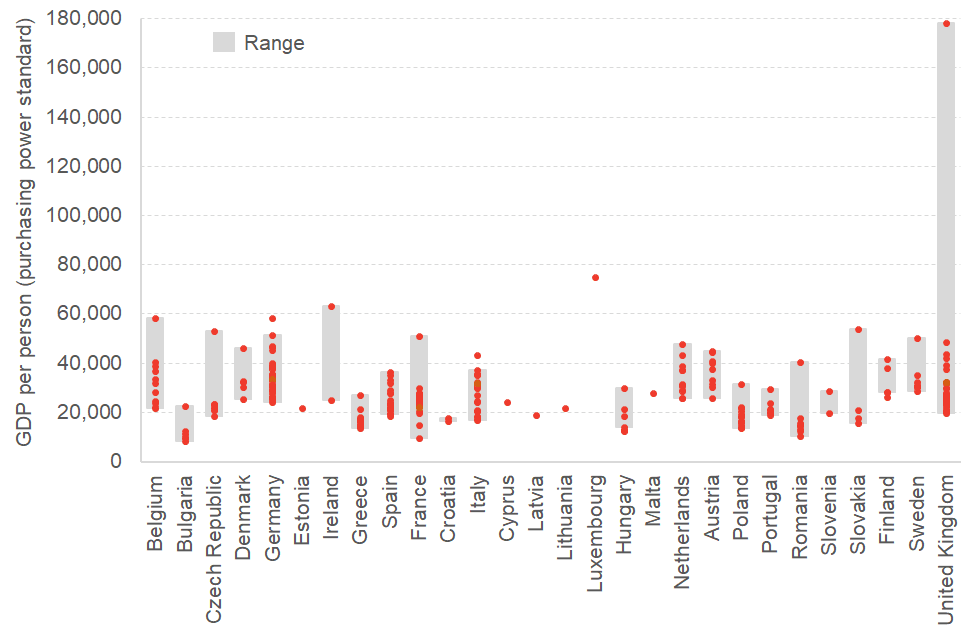

Looking at the more disaggregated data the disparity is even greater. It is clear that the UK, or more specifically one part of London, stands as an outlier in Europe. (Chart 50)

Chart 50: GVA per head, difference between richest and poorest parts of EU countries (NUTS2 regions, 2016)

One might expect the dominance of London to have waned following the financial crisis. If anything it has increased, widening UK interregional disparities.

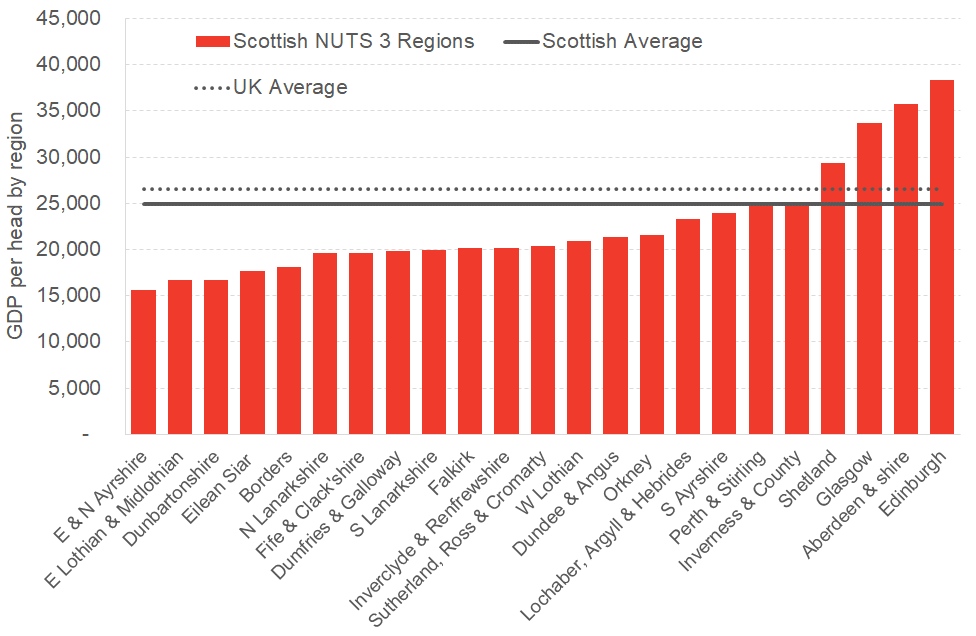

But before we think that this is just a London or UK phenomenon, the same data also reveals the scale of regional inequality in Scotland. (Chart 51)

Chart 51: GVA per head Scotland’s NUTS 2 regions (2016)

GVA per head in Edinburgh is nearly 2.5 times higher than in East and North Ayrshire. And over time, the gap has widened. GVA per head in the capital has nearly doubled since devolution, with growth in East and North Ayrshire around half that rate.

This translates into widening economic and social outcomes across Scotland. In North Ayrshire for example, around a third of children are in households classified as being in relative poverty.

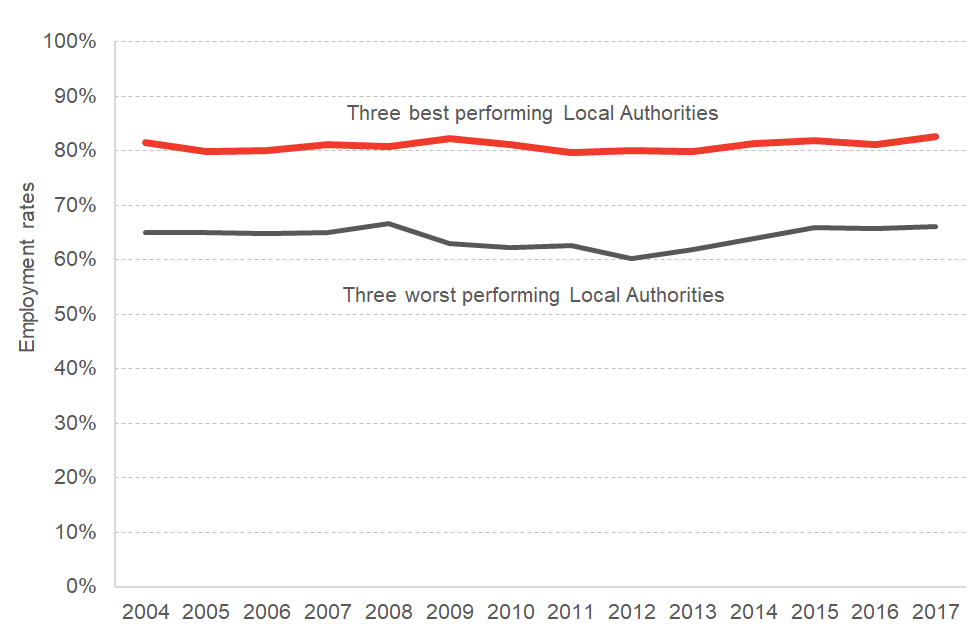

And back in 2007, the Scottish Government established a target to narrow the gap in employment between the three ‘best‘ performing and the three ‘worst’ performing local authorities in Scotland.

As the chart below highlights, a decade later, the gap remains largely the same. (Chart 52)

Chart 52: Difference in employment rate for the three best and worst performing Local Authorities (2004 – 2017)

The Centre for Regional Inclusive Growth

This summer the Scottish Government launched its Centre for Regional Inclusive Growth.

So far this is a website. It pulls together local information and statistics. But the Centre does not (yet) offer any fresh insights into how to tackle the questions that have underpinned this policy area for decades.

Indeed, on policy solutions, evaluation of current programmes or plans for new investment, it is silent.

The website points to Regional Partnerships which are to come forward with new ideas but there is little detail on what resource will be made available and how ‘asks’ to central government will be acted upon.

Perhaps we will see more in the upcoming Budget.

Policy opportunities and challenges with Regional Inclusive Growth

So one cannot help follow recent UK and Scottish Government initiatives and ask the question – “so what happens next?” It is hard not to be sceptical over any hope that current initiatives will tackle the wide and deep-rooted variations in economic performance across Scotland.

Narrowing regional inequalities is not easy. The challenges are complex and – often – deep-rooted.

Firstly, there are a great many structural factors why some parts of the country lag behind.

For example, the industrial mix of regions varies significantly. Many of the challenges that parts of west central Scotland face can be traced to the rapid de-industrialisation of the 1970s and 1980s and a reliance on relatively low value service industries.

Social deprivation and health barriers often act as self-reinforcing barriers to economic prosperity. Geography also plays a part, with much of Scotland subject to the challenges of rurality and remoteness. Parts of our cities struggle with poor housing stock and wider basic infrastructure.

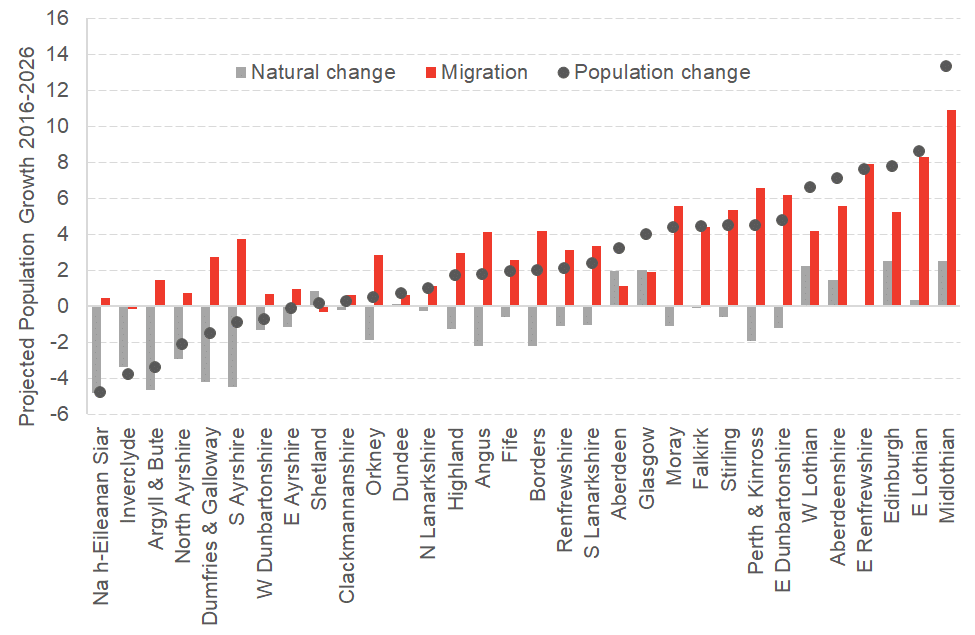

The make-up of a region’s population can also act as a significant drag on long-term growth. Some of the most fragile parts of the country are on track to lose population over the next few years. (Chart 53)

Chart 53: Projected population growth in Local Authorities in Scotland, 2016-2026

Secondly, local areas often lack the tools to turnaround their economic performance (beyond limited interventions at the margins). Many of the levers that will make a difference – jobs, health and well-being, population, digital and transport connectivity – are national responsibilities.

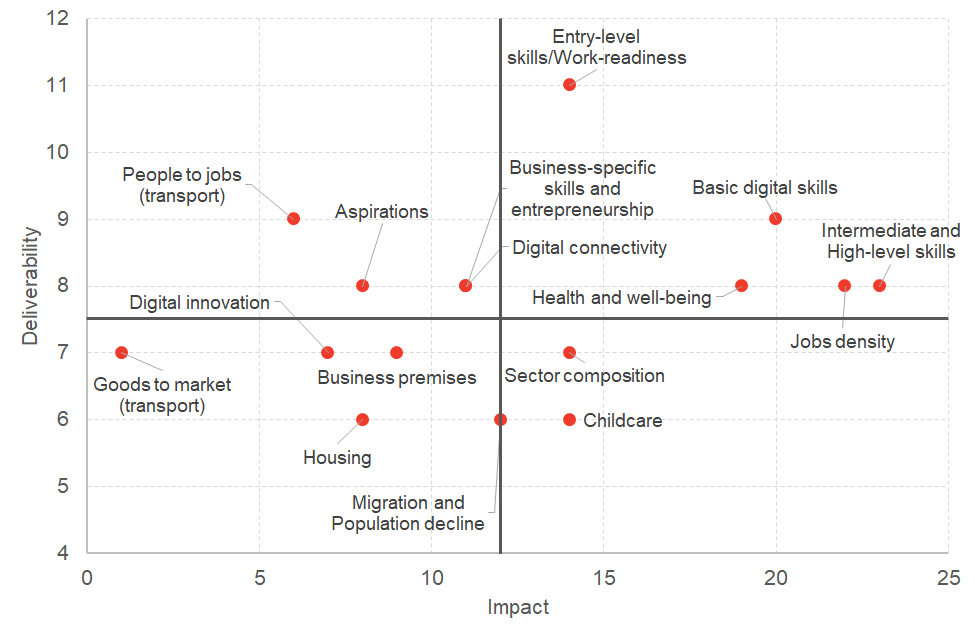

Indeed, a quick glance at the diagnostic results from the Centre’s pilot study for North Ayrshire poses the question, “what realistic levers do local policymakers have to effect change in these areas?” (Chart 54)

At the same time, local government budgets have been squeezed putting pressure on local government jobs and wages. As local authorities prioritise statutory responsibilities, it is no surprise that many have scaled back support for economic development.

Chart 54: Prioritisation matrix for North Ayrshire

Interestingly, the mechanism for funding local authorities has not changed much over time, and certainly not since regional inclusive growth has risen up the policy agenda. Perhaps that needs to change?

Thirdly, there is often a basic tension at the heart of national economic policy over where resources are targeted, particularly in a world of tight public spending.

On the one hand, prioritising policy efforts at areas of economic strength – like the strong parts of our cities – can create spill-overs, promote international competitiveness and lead to national benefits. But on the other hand, it is arguably only by shifting resources to areas in economic need that can one realistically expect gaps to be narrowed.

We have seen this played out in recent months, most visibly in the case of North Ayrshire.

The decision to locate the new Medicines Manufacturing Innovation Centre (MMIC) close to Glasgow Airport might make sense from an agglomeration and connectivity perspective. From an inclusive growth perspective, it passed up an opportunity to support private sector activity and the creation of skilled jobs – as part of an Ayrshire Growth Deal – in an area of the country where such investment is rarely undertaken and much needed.

The decision to locate the new Social Security Agency in Dundee was another such example. On this occasion, despite North Ayrshire being clearly identified as scoring best for ‘inclusive growth’ it was passed over by national policy makers because it was felt that the local authority might struggle to attract people to work there (despite transport links improving).

Anyone can agree or disagree with such a decision, and few would argue with the importance of ensuring that the new Social Security Agency performs effectively from day one. But it arguably highlights that even the Scottish Government itself – the key advocate of regional inclusive growth – often finds it difficult to back-up its vision with investment and funding support.

Finally, and an issue we have raised in previous commentaries, is that in attempting to be ‘all-things-to-all-people’, the policy landscape can become complex and cluttered.

Currently, we have a patchwork of 32 local authorities, various City-Region Deals, a new suite of Regional Partnerships, not to mention the large number of strategies and programmes many of which have their own regional dimension (including 32 Single Outcome Agreements).

Coordinating such activity across boundaries, different tiers of government (and governance) – often of different political hues – inevitably makes for a complex delivery landscape.

Summary

Delivering regional inclusive growth is not easy.

Regional disparities reflect decades of social and economic change, as well as the basic geography of Scotland.

The Scottish Government should be commended for pushing it up the policy agenda.

Ultimately, however, tackling regional inequalities will only be achieved by investing significantly in Scotland’s more fragile economic communities, finding out what works (and what does not) and prioritising some areas of the country over others whatever the impact on wider economic and political objectives.

Otherwise, we run the risk of continuing to talk about these issues while regional inequalities continue to widen.

Authors

The Fraser of Allander Institute (FAI) is a leading economy research institute based in the Department of Economics at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.